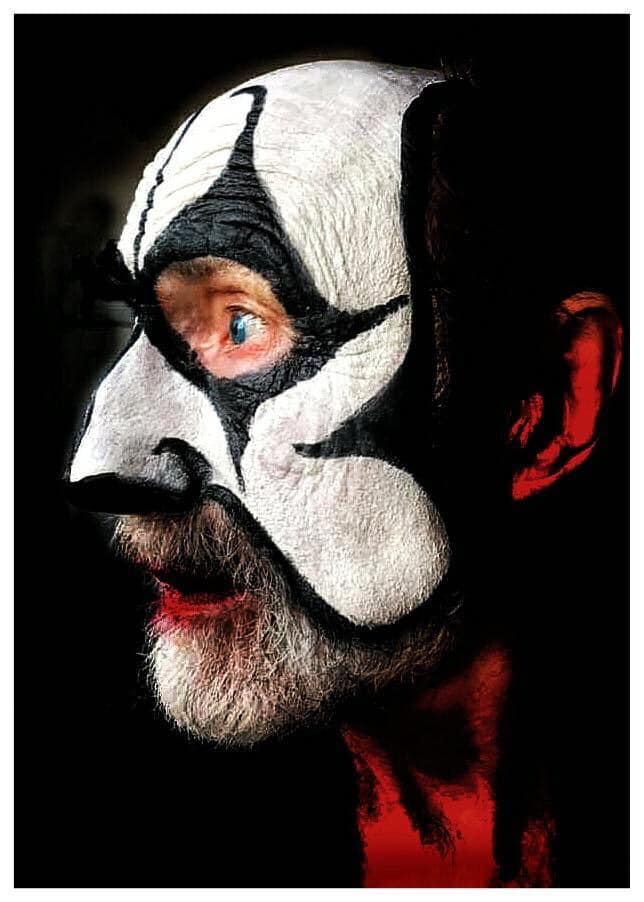

Interview: Arthur Brown

Interview: Arthur Brown

on the Origin of The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, a Drum Machine Possessed, Working with The Pretty Things, and a New Single

LeValley: Nice to meet you, Arthur. Brown: Nice to meet you, Jason.

LeValley: So you’ve got a new single out called “Zombie Yelp”. What inspired you to put out a single at this point in time?

Brown: Well, it was arranged through Cleopatra Records, and it comes out through Pyramid. Purple Pyramid is the label they’ve got. But they wanted to do a horror album, mainly stuff from way back in the 50s and moving it musically up into the present.

LeValley: What do you mean? They wanted to do a horror album with you or with various artists?

Brown: Well, it’s with me, basically. But then they will have other artists coming in to make the, you know, interesting music. For instance, on “Zombie Yelp”, it’s Mark Stein of Vanilla Fudge and he’s playing Hammond, which, of course, I’ve got a lot of association with the Hammond.

LeValley: I didn’t realize that, but I did see Vanilla Fudge in concert here in Tucson just a couple of years ago. And I was wondering, you know, I listened to the song on Spotify and it said, in addition to your name, Mark Stein, and I didn’t know who that was.

Brown: Yeah. And it’s produced by Alan Davey, who has a connection and used to play with Hawkwind. So this is the album which he is putting out now, not to confuse it too much. And I’ve got a track on that one called “Glass Wolves”. Alan likes to take the sound and mess it around and add people and make it into a great piece of music. And I think he has done that indeed.

LeValley: One of the things that I just learned about you is that you were a member of Hawkwind for a time.

Brown: I was invited to be the dramatic lead singer and that went on for about, I think, six months.

LeValley: Ok, and what period of time was this?

Brown: That would have been around about 2003 or something like that.

LeValley: Ok, I’ve always been a little bit confused about the name. You know, it looks like the artist’s name is The Crazy World of Arthur Brown. And I’ve never been clear if that was just the name of the album or if that was the name of the artist. If you could clarify that a little bit, that’d be great.

Brown: Ok, well, I arrived back in London from singing in Paris, my first professional engagement. And I’ve moved into this bohemian lodging place. And lo and behold, I heard this magnificent piano and I went upstairs and there was Vincent Crane, who turned out to also play the Hammond. In those days, he was playing the L-100, which we moved on from when it caught fire and the valves inside, which had gas and all kinds of things in them, burned with a green flame. And that was the end of that keyboard. And he moved on to the B3 and then the C3. And so he had a small band. We did a few gigs together. And I had an idea of presenting a band that was more multimedia and based in R & B and jazz. And so we put an advert in the Melody Maker. And up came this fellow calling himself Drachen Theaker, and we said, “How did you get that name?” He said, “I was given it by Wynder K. Frog. And so Wynder K. Frog was a guy who was pretty important in the early R & B scene in England. And so we had myself, Vincent Crane, Drachen Theaker on drums. Vincent played foot pedal bass and then the two hands of the keyboard. And I sang and leapt about and wore costumes, et cetera. And so, because it was my project, if you like, the whole direction, it became my band. And so it was called The Crazy World of Arthur Brown.

LeValley: Ok, so that was the band name. Thanks for clarifying that. That’s something that I’ve wondered about for many years.

Because it was my project, if you like, the whole direction, it became my band. And so it was called The Crazy World of Arthur Brown.

LeValley: Did you ever think back in 1968 that you’d be recording rock and roll in 2020… or in your late 70s?

Brown: Well, no, not at all. I mean, that was before, say, Led Zeppelin and everything turned around and the artists started to make lots of money on gigs instead of the promoter making all that money. It was Peter Grant who got that changed around. Suddenly the artist was earning 80 percent of the door, whereas before they were earning maybe 20. And so suddenly, they started to be rich. But before that, mainly your career was three years. And if you were over 21, they did take away two years from your age, so I was put out in ’68 when “Fire” was a hit. I was 26, but I was advertised as being 24. That was Track Records. So I had to be younger. And so you didn’t expect that it was going to be a long-term thing at all.

LeValley: Nice to meet you, Arthur. Brown: Nice to meet you, Jason.

LeValley: So you’ve got a new single out called “Zombie Yelp”. What inspired you to put out a single at this point in time?

Brown: Well, it was arranged through Cleopatra Records, and it comes out through Pyramid. Purple Pyramid is the label they’ve got. But they wanted to do a horror album, mainly stuff from way back in the 50s and moving it musically up into the present.

LeValley: What do you mean? They wanted to do a horror album with you or with various artists?

Brown: Well, it’s with me, basically. But then they will have other artists coming in to make the, you know, interesting music. For instance, on “Zombie Yelp”, it’s Mark Stein of Vanilla Fudge and he’s playing Hammond, which, of course, I’ve got a lot of association with the Hammond.

LeValley: I didn’t realize that, but I did see Vanilla Fudge in concert here in Tucson just a couple of years ago. And I was wondering, you know, I listened to the song on Spotify and it said, in addition to your name, Mark Stein, and I didn’t know who that was.

Brown: Yeah. And it’s produced by Alan Davey, who has a connection and used to play with Hawkwind. So this is the album which he is putting out now, not to confuse it too much. And I’ve got a track on that one called “Glass Wolves”. Alan likes to take the sound and mess it around and add people and make it into a great piece of music. And I think he has done that indeed.

LeValley: One of the things that I just learned about you is that you were a member of Hawkwind for a time.

Brown: I was invited to be the dramatic lead singer and that went on for about, I think, six months.

LeValley: Ok, and what period of time was this?

Brown: That would have been around about 2003 or something like that.

LeValley: Ok, I’ve always been a little bit confused about the name. You know, it looks like the artist’s name is The Crazy World of Arthur Brown. And I’ve never been clear if that was just the name of the album or if that was the name of the artist. If you could clarify that a little bit, that’d be great.

Brown: Ok, well, I arrived back in London from singing in Paris, my first professional engagement. And I’ve moved into this bohemian lodging place. And lo and behold, I heard this magnificent piano and I went upstairs and there was Vincent Crane, who turned out to also play the Hammond. In those days, he was playing the L-100, which we moved on from when it caught fire and the valves inside, which had gas and all kinds of things in them, burned with a green flame. And that was the end of that keyboard. And he moved on to the B3 and then the C3. And so he had a small band. We did a few gigs together. And I had an idea of presenting a band that was more multimedia and based in R & B and jazz. And so we put an advert in the Melody Maker. And up came this fellow calling himself Drachen Theaker, and we said, “How did you get that name?” He said, “I was given it by Wynder K. Frog. And so Wynder K. Frog was a guy who was pretty important in the early R & B scene in England. And so we had myself, Vincent Crane, Drachen Theaker on drums. Vincent played foot pedal bass and then the two hands of the keyboard. And I sang and leapt about and wore costumes, et cetera. And so, because it was my project, if you like, the whole direction, it became my band. And so it was called The Crazy World of Arthur Brown.

LeValley: Ok, so that was the band name. Thanks for clarifying that. That’s something that I’ve wondered about for many years.

Because it was my project, if you like, the whole direction, it became my band. And so it was called The Crazy World of Arthur Brown.

LeValley: Did you ever think back in 1968 that you’d be recording rock and roll in 2020… or in your late 70s?

Brown: Well, no, not at all. I mean, that was before, say, Led Zeppelin and everything turned around and the artists started to make lots of money on gigs instead of the promoter making all that money. It was Peter Grant who got that changed around. Suddenly the artist was earning 80 percent of the door, whereas before they were earning maybe 20. And so suddenly, they started to be rich. But before that, mainly your career was three years. And if you were over 21, they did take away two years from your age, so I was put out in ’68 when “Fire” was a hit. I was 26, but I was advertised as being 24. That was Track Records. So I had to be younger. And so you didn’t expect that it was going to be a long-term thing at all.

LargoPhoto

LeValley: Yes. So I noticed that you have a Master’s in Counseling. I actually have one of those, too. Have you put yours to use?

Brown: Do you need any help? (Laughs)

LeValley: Yes. I think everybody that pursues a degree in psychology needs help. (Laughs) No, I worked as a high school guidance counselor for a while, so I did put it to use. What about you?

Brown: I did some time in a kind of crisis center for young people on abuse and drugs and stuff, you know, and that was, you know, you get burned out pretty quick in those places. Well, what we did, though, was I had a friend who got qualified at the same time I did and he was a great talker as a counselor. His timing was incredible, and so I would listen to the session that he was doing, and then I would be picking up on all sorts of issues, kind of unconsciously, really. And so we come to the end of the talking bit and up would come my guitar and I would make up a song. It wasn’t just a form where I just filled in the people’s names. It was always different. Sometimes it was a poem and sometimes it was eight minutes long. Sometimes it was three. You know, it would depend on what had come out through the session. Then we would give them a recording of it and they take it home and listen whenever they felt like, “Oh, I want to listen to that thing and see what else I can find in it.” And so I was in Life magazine or one of those big magazines as having been the God of Hellfire and transformed into the singing shrink.

LeValley: You know, I’ve had the CD The Crazy World of Arthur Brown for many years now. I was just listening to it this morning and I noticed for the first time ever that Pete Townsend was credited as being the associate producer. I’m not even sure what an associate producer does as opposed to a regular producer. But what was his involvement with that project?

Brown: Well, the thing was that we were playing down the UFO Club and it began to get, you know, red hot and all the major record companies were coming down here.

Brown: And a friend of mine, he became my friend later, John Fenton, came down and saw me playing, not at the UFO, but The Speakeasy, went over and told Townshend and he came down to UFO and said, “Well, I want to persuade the record company who put me out and The Who to get involved with you guys. So would you come to my studio and I’ll make demos. “What have you got?” And I said, “Well, I’ve got this concept of blah, blah, blah.” And so he made the demos with us and we didn’t have any experience in the studio. And he was really very helpful, very encouraging of creativity, very much aware of what might be just a little too much for the studio or for the equipment. And so it was very helpful. And he was originally on some of the demos. But of course, when when it came to putting out the band, they wanted just the band to be playing.

LeValley: I also read that you narrated The Pretty Things live version of their psychedelic classic album SF Sorrow–definitely an underappreciated record, in my opinion. But how did that come to be? Did you know those guys back in the 60s? Because I know that you did that in 1999, I believe.

Brown: Yeah. I didn’t really know them in the 60s. Of course, I saw them on TV when they were monsters and had the longest hair in England and all of that stuff. But somebody who managed me at that time was also there. And so he liked my speaking voice. He was also a good recording producer, you know, so he liked my speaking voice and thought of the idea of having me narrate the story. And I had a little acoustic line-up at that time and we’d done a lot of concerts together. And I also would get up and sing with Phil, who would sort of have me up on stage, so I’d sing with The Pretty Things. And that was wonderful. I thought Phil was really a very kind man and a man who could sing with passion, you know. And so I was very, very sad when he passed away.

LeValley: That was just this year, wasn’t it?

Brown: Yeah, yeah. In fact, we played in Nell’s Blues Bar in London. Crazy World played and they came down on the second evening, Dick and Phil. Dick Taylor and Phil May and we sang together and that was the last time I was I think that was the last concert they did before Phil died.

LeValley: Did you appear on any Pretty Things recordings?

Brown: No. Oh, well, we did a lot of well, I’m not really sure. The rest of SF Sorrow, of course, was recorded. I don’t know. David Gilmore was playing guitar and I did sing three songs at the end of the set. But I’m not sure whether that was included on the album because, you know, they wanted to have it as SF Sorrow—the presentation. So the gig is different from that. You want everybody to be jumping up and down and all that. So I did that.

LeValley: Another thing that I read about you is that you were using a drum machine–like in the early 70s, which was pretty much unheard of at that time. How did you get involved with the early drum machines?

Brown: Well, it came about that we had some gigs and there was a period of about five weeks before the gig and the bass player called up and the drummer called up and said, “I’m up here with the bass player, his wife, and I’ve got your van.” And I just thought, “Oh, we’ve had three troublesome drummers in that band.” It’s not always like that. And so I just thought, “Well, what can we do? We don’t want to be looking around and just shoving somebody in.” So why don’t you use the machine? “Why don’t we use the machine?” came the idea. And the Bentley Rhythm Ace was out then and so we designed the whole set. There were four. There was myself playing the drums. It was Andy Dalby on guitar, Phil Curtis on bass, and Gooch Harris in the original band. And then it moved on to an American guy called Victor Peraino. And we decided we wanted to make it the rock and roll equivalent of a quartet of musicians, you know, a classical quartet so that there’s space for each instrument and we’re not crowding each other out. And there would be intricate interplay between the instruments. And we played all sorts of musical games to get used to that and then just wrote the music around the drums. It was a very simple drum machine and nobody else had done that.

LeValley: Right. And did you program it? I mean, the wording that I read said that you played the drum machine.

Brown: Yeah, it had knobs on the front and buttons. What was amazing was to be in the middle of a slow baroque piece. And then you just press three of the Latin American buttons and you’ve got a huge percussion orchestra. And the only problem we had was on one particular gig. The machine, of course, runs on electronics and it has all these synapses. I switch the signals, go to the different drums and things, and on this particular night in The Marquee, it was so hot. The liquid, you know, sweat was dripping from the ceiling and condensation of breath and it got in the drum machine and it played itself. So we had to go on for 40 minutes following the drum machine. And so we just made up the music while the roadies threw in a prop every so often. I’d make up the lyrics to go with it and the audience loved it. But it was… (laughs) Fortunately we didn’t have any more places that were so hot and so sweaty.

LeValley: Right. So you just said the condensation made the drum machine play itself? Is that what you said, that the condensation caused the drum machine to play?

Brown: Yeah, it was turned off obviously, and I was about to start the set, but the things dripped into it and the next thing we knew, it had taken off by itself (laughs) and I couldn’t do anything with it. So I just sat back, let the drum machine do the whole set. We made up the spontaneous set because we had to follow the drum machine. And then threw in words and the prop and the audience loved it. It was a good gig, you know, just fine. Sometimes you get lucky.

LeValley: Yeah. I mean, it seems like it could have gone haywire really quickly if it was not really under your control. That’s great.

Brown: In fact, that band made an album that was finally remixed and overproduced by Dave Edmunds, who had a great love of electronics and things. And in the coming March, April, Esoteric Records, which is…My back catalog is with Cherry Ray, and they have sub-deals with different people and so Esoteric are putting out the music from that album called Journey and then the two previous albums by that band, before the drum machine, and so that’ll be a package coming out next spring, which should be… I think they’re good albums.

So we had to go on for 40 minutes following the drum machine and we just made up the music while the roadies threw in a prop every so often.

LeValley: Yes. So I noticed that you have a Master’s in Counseling. I actually have one of those, too. Have you put yours to use?

Brown: Do you need any help? (Laughs)

LeValley: Yes. I think everybody that pursues a degree in psychology needs help. (Laughs) No, I worked as a high school guidance counselor for a while, so I did put it to use. What about you?

Brown: I did some time in a kind of crisis center for young people on abuse and drugs and stuff, you know, and that was, you know, you get burned out pretty quick in those places. Well, what we did, though, was I had a friend who got qualified at the same time I did and he was a great talker as a counselor. His timing was incredible, and so I would listen to the session that he was doing, and then I would be picking up on all sorts of issues, kind of unconsciously, really. And so we come to the end of the talking bit and up would come my guitar and I would make up a song. It wasn’t just a form where I just filled in the people’s names. It was always different. Sometimes it was a poem and sometimes it was eight minutes long. Sometimes it was three. You know, it would depend on what had come out through the session. Then we would give them a recording of it and they take it home and listen whenever they felt like, “Oh, I want to listen to that thing and see what else I can find in it.” And so I was in Life magazine or one of those big magazines as having been the God of Hellfire and transformed into the singing shrink.

LeValley: You know, I’ve had the CD The Crazy World of Arthur Brown for many years now. I was just listening to it this morning and I noticed for the first time ever that Pete Townsend was credited as being the associate producer. I’m not even sure what an associate producer does as opposed to a regular producer. But what was his involvement with that project?

Brown: Well, the thing was that we were playing down the UFO Club and it began to get, you know, red hot and all the major record companies were coming down here.

Brown: And a friend of mine, he became my friend later, John Fenton, came down and saw me playing, not at the UFO, but The Speakeasy, went over and told Townshend and he came down to UFO and said, “Well, I want to persuade the record company who put me out and The Who to get involved with you guys. So would you come to my studio and I’ll make demos. “What have you got?” And I said, “Well, I’ve got this concept of blah, blah, blah.” And so he made the demos with us and we didn’t have any experience in the studio. And he was really very helpful, very encouraging of creativity, very much aware of what might be just a little too much for the studio or for the equipment. And so it was very helpful. And he was originally on some of the demos. But of course, when when it came to putting out the band, they wanted just the band to be playing.

LeValley: I also read that you narrated The Pretty Things live version of their psychedelic classic album SF Sorrow–definitely an underappreciated record, in my opinion. But how did that come to be? Did you know those guys back in the 60s? Because I know that you did that in 1999, I believe.

Brown: Yeah. I didn’t really know them in the 60s. Of course, I saw them on TV when they were monsters and had the longest hair in England and all of that stuff. But somebody who managed me at that time was also there. And so he liked my speaking voice. He was also a good recording producer, you know, so he liked my speaking voice and thought of the idea of having me narrate the story. And I had a little acoustic line-up at that time and we’d done a lot of concerts together. And I also would get up and sing with Phil, who would sort of have me up on stage, so I’d sing with The Pretty Things. And that was wonderful. I thought Phil was really a very kind man and a man who could sing with passion, you know. And so I was very, very sad when he passed away.

LeValley: That was just this year, wasn’t it?

Brown: Yeah, yeah. In fact, we played in Nell’s Blues Bar in London. Crazy World played and they came down on the second evening, Dick and Phil. Dick Taylor and Phil May and we sang together and that was the last time I was I think that was the last concert they did before Phil died.

LeValley: Did you appear on any Pretty Things recordings?

Brown: No. Oh, well, we did a lot of well, I’m not really sure. The rest of SF Sorrow, of course, was recorded. I don’t know. David Gilmore was playing guitar and I did sing three songs at the end of the set. But I’m not sure whether that was included on the album because, you know, they wanted to have it as SF Sorrow—the presentation. So the gig is different from that. You want everybody to be jumping up and down and all that. So I did that.

LeValley: Another thing that I read about you is that you were using a drum machine–like in the early 70s, which was pretty much unheard of at that time. How did you get involved with the early drum machines?

Brown: Well, it came about that we had some gigs and there was a period of about five weeks before the gig and the bass player called up and the drummer called up and said, “I’m up here with the bass player, his wife, and I’ve got your van.” And I just thought, “Oh, we’ve had three troublesome drummers in that band.” It’s not always like that. And so I just thought, “Well, what can we do? We don’t want to be looking around and just shoving somebody in.” So why don’t you use the machine? “Why don’t we use the machine?” came the idea. And the Bentley Rhythm Ace was out then and so we designed the whole set. There were four. There was myself playing the drums. It was Andy Dalby on guitar, Phil Curtis on bass, and Gooch Harris in the original band. And then it moved on to an American guy called Victor Peraino. And we decided we wanted to make it the rock and roll equivalent of a quartet of musicians, you know, a classical quartet so that there’s space for each instrument and we’re not crowding each other out. And there would be intricate interplay between the instruments. And we played all sorts of musical games to get used to that and then just wrote the music around the drums. It was a very simple drum machine and nobody else had done that.

LeValley: Right. And did you program it? I mean, the wording that I read said that you played the drum machine.

Brown: Yeah, it had knobs on the front and buttons. What was amazing was to be in the middle of a slow baroque piece. And then you just press three of the Latin American buttons and you’ve got a huge percussion orchestra. And the only problem we had was on one particular gig. The machine, of course, runs on electronics and it has all these synapses. I switch the signals, go to the different drums and things, and on this particular night in The Marquee, it was so hot. The liquid, you know, sweat was dripping from the ceiling and condensation of breath and it got in the drum machine and it played itself. So we had to go on for 40 minutes following the drum machine. And so we just made up the music while the roadies threw in a prop every so often. I’d make up the lyrics to go with it and the audience loved it. But it was… (laughs) Fortunately we didn’t have any more places that were so hot and so sweaty.

LeValley: Right. So you just said the condensation made the drum machine play itself? Is that what you said, that the condensation caused the drum machine to play?

Brown: Yeah, it was turned off obviously, and I was about to start the set, but the things dripped into it and the next thing we knew, it had taken off by itself (laughs) and I couldn’t do anything with it. So I just sat back, let the drum machine do the whole set. We made up the spontaneous set because we had to follow the drum machine. And then threw in words and the prop and the audience loved it. It was a good gig, you know, just fine. Sometimes you get lucky.

LeValley: Yeah. I mean, it seems like it could have gone haywire really quickly if it was not really under your control. That’s great.

Brown: In fact, that band made an album that was finally remixed and overproduced by Dave Edmunds, who had a great love of electronics and things. And in the coming March, April, Esoteric Records, which is…My back catalog is with Cherry Ray, and they have sub-deals with different people and so Esoteric are putting out the music from that album called Journey and then the two previous albums by that band, before the drum machine, and so that’ll be a package coming out next spring, which should be… I think they’re good albums.

So we had to go on for 40 minutes following the drum machine and we just made up the music while the roadies threw in a prop every so often.

LeValley: You know, I’ve watched the video of your performance on Top of the Pops from 1968 a number of times, and it’s always very engaging. It occurred to me that you really, as far as I know, were like the first shock rocker. I had always thought of Alice Cooper as being the one that kind of founded that concept. But you beat him to it.

Brown: He always says without Arthur Brown there wouldn’t be an Alice Cooper. It’s not like he’s trying to pretend he did it. I mean, his publicity may say that, but he doesn’t. But, you know, if you look, I feel that I’m part of a long train of theater in music, music hall, the early rock and roll musicals like (singing) “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be”, which was one of the early musicals. And although it was different, you of course had Lord Sutch who did some of his horror stuff, who I knew. And then you had Screaming Jay Hawkins, who was a great performer and wrote astonishing pieces of music. So I feel… yes, I was the one who introduced it at that time, and certainly nobody else had had a fire helmet.

LeValley: Right. Yeah. I read that you burned yourself at one point. I would imagine, being the God of Hellfire, that you burned yourself more than just the one time when you’re performing with fire on your head.

Brown: Oh, yeah. It is dangerous. But then of course, gradually you get to learn how to use it and then it depends. You’ve got to get the right person to be looking after the helmet and lighting it and filling it with the fluid and all of that. And if they screw up on a particular night, that could bring a problem. So we’ve now got one that that won’t happen with. It’s gradually going through all the years. It started as a candle on a crown and now it’s got this… Yeah. You’re not going to start fights with this one.

LeValley: Oh. So you still use the fire helmet?

Brown: Very occasionally. It depends on the size of the room. You can’t do it in a small room these days. In those days, there wasn’t any Health and Safety. But yeah, we still use it on some of the good performances and we’ve got a really great show. And that has brought a lot of the elements from the Kingdom Come band– the electronic band with its visual show projections. This show we’re doing now, which is called A Human Perspective, has an amazing visual side. It’s based on lines, movement. The dance movements are designed to bring light and shadow onto the stage rather than being, you know like I’m going to have a good time down at the club and the light’s projection is quite amazing. Andy, who does the lighting with Yes. And what has happened is that what was perhaps behind a movement in the 70s, that what the technology can do now in sound, in linking lights with the sound, in the lights man having as much control over the lighting and the movement of color. And if they’ve got the imagination, it’s just as complex as a guitar solo. And it’s beautiful. So we have a very good show. We’ve also got a new album coming out. Just signed a new record deal. I can’t reveal yet who the company is, but that’s the new album coming out next year.

LeValley: And this song “Zombie Yelp” will be on it, I assume?

Brown: Oh, no, no, it’s a different record company. With Cleopatra, I’ve just done the pieces of work with Alan Davey and the one of which is the album and the other is the solo track. Oh, except that I think we added another guest performance with… There are some people who got together to do a tribute to Emerson, Lake, Palmer. And I did the song, (sings) “Welcome back, my friends, to the show that never ends. I’m so glad you could attend. Come inside, come inside.” And I did that with Carl Palmer’s ELP Legacy on the last big tour.

LeValley: Right. Carl Palmer was in your original band, right?

Brown: He was, yeah. After Drachen Theaker, Carl came in and it was he who was on the video as the drummer. And he was with The Crazy World for about a year and a half before he and Vincent went and formed Atomic Rooster. And they got three Top 10 hits, too.

LeValley: They must have been UK hits. I don’t think they ever had any kind of commercial success in the US.

Brown: No, it was U.K. I’m not sure what the problem was with the States, but something.

LeValley: So I didn’t know about the new album. Do you plan on touring when things settle down?

Brown: When things get back to the place where we could actually sit near each other. (Someone speaks in the background) That voice in the background is my partner and manager Claire…Claire Weller, who also was the guiding person for this show that we do. And she’s the creative director of our stage show. And also the new album. She’s the creative director of the new album we’re going to do now. Also, I’ve just done, I’ll fill you in because it’s a time when I’m busier than I’ve been just about the whole of my life, I think. But it’s all different things going on. We just about eight weeks ago put out a charity single. It was the idea of Ian Grant and Paul Mitchell, and it was to help raise money for musicians. Because particularly in England, the government helps classical musicians but normal, everyday, uh, popular musicians, no. So we just wanted to try and raise some money. So we put out a version of House of the Rising Sun with a stellar collection of musicians, one of whom was, for a while, in The Crazy World. It’s had a lot of good interest. So we’re about to put out another one. Which again, I can’t say anything about. (Laughs) And it’s just to keep the idea, you know, going that maybe something should be done about musicians. See, the English government guy said, “Well, when it comes down to those musicians, they should all retrain in another industry. That’s not a real job. I think you should go and get a real job.”

Brown: Finally I’m doing another single. This one is with a Peruvian band. Claire came across this piece of music on the internet and she said, “Listen to this”, and it was a band with this amazing flute player, so she wrote to the band and said, “We really like your music.”

Claire Waller: No, actually, they were going to play New Day this year. We were going to play together.

Brown: Yeah. And they were booked for the New Day Festival in England, which we’re also playing. And so it ended up the manager of that band got in touch and said, “Well, we’re doing this new single. Would you listen to it and tell us what you think?” So we did. And they used that on the publicity for their new single. So that was good. That was nice. And then they said, “Well, that was really good. And the guy who’s producing the album, Roy Z, works with Bruce Dickinson, he’s got a track that he originally wrote for you to sing on a Bruce Dickinson album, but in the end, what they had that was a little, you know, to have suddenly a guest artist doing the main song on that album would have overbalanced the album so they didn’t use it. So the Peruvian band, they’re called Flor De Loto, they recorded the backing track for it being produced by Roy, who wrote it. And so now I’ve written the lyrics for it and we’re recording it and that’ll come out soon.

LeValley: And this is with the Peruvian band?

Brown: Yes.

LeValley: OK. Is it like traditional Peruvian music or is it more like rock and roll?

Brown: Well, the flute player, for instance, is of the original indigenous tribes from Peru, and he plays the traditional flute more in the realm of the way that, say, Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull. In that feel rather than just playing a traditional style of music. But this guy is the leading flute player of that tribe of people, that whole mast of the original inhabitants. He’s regarded as their best player. So he’s a member of the band and they play prog music based on heavy metal, and obviously a touch of world music.

LeValley: Ok, that hasn’t been released yet, right?

Brown: No, it isn’t finished yet. (Turns to Claire) When will that be released?

Claire Waller: I think probably about a month.

Brown: Yeah, that will probably come out in about a month.

LeValley: Ok, well, I want to thank you for taking the time to speak with me today or tonight. I guess it’s night over there. It’s really an honor.

Brown: Well, it’s a great pleasure to do it.

This article originally appeared in It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine on December 6th, 2020.

LeValley: You know, I’ve watched the video of your performance on Top of the Pops from 1968 a number of times, and it’s always very engaging. It occurred to me that you really, as far as I know, were like the first shock rocker. I had always thought of Alice Cooper as being the one that kind of founded that concept. But you beat him to it.

Brown: He always says without Arthur Brown there wouldn’t be an Alice Cooper. It’s not like he’s trying to pretend he did it. I mean, his publicity may say that, but he doesn’t. But, you know, if you look, I feel that I’m part of a long train of theater in music, music hall, the early rock and roll musicals like (singing) “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be”, which was one of the early musicals. And although it was different, you of course had Lord Sutch who did some of his horror stuff, who I knew. And then you had Screaming Jay Hawkins, who was a great performer and wrote astonishing pieces of music. So I feel… yes, I was the one who introduced it at that time, and certainly nobody else had had a fire helmet.

LeValley: Right. Yeah. I read that you burned yourself at one point. I would imagine, being the God of Hellfire, that you burned yourself more than just the one time when you’re performing with fire on your head.

Brown: Oh, yeah. It is dangerous. But then of course, gradually you get to learn how to use it and then it depends. You’ve got to get the right person to be looking after the helmet and lighting it and filling it with the fluid and all of that. And if they screw up on a particular night, that could bring a problem. So we’ve now got one that that won’t happen with. It’s gradually going through all the years. It started as a candle on a crown and now it’s got this… Yeah. You’re not going to start fights with this one.

LeValley: Oh. So you still use the fire helmet?

Brown: Very occasionally. It depends on the size of the room. You can’t do it in a small room these days. In those days, there wasn’t any Health and Safety. But yeah, we still use it on some of the good performances and we’ve got a really great show. And that has brought a lot of the elements from the Kingdom Come band– the electronic band with its visual show projections. This show we’re doing now, which is called A Human Perspective, has an amazing visual side. It’s based on lines, movement. The dance movements are designed to bring light and shadow onto the stage rather than being, you know like I’m going to have a good time down at the club and the light’s projection is quite amazing. Andy, who does the lighting with Yes. And what has happened is that what was perhaps behind a movement in the 70s, that what the technology can do now in sound, in linking lights with the sound, in the lights man having as much control over the lighting and the movement of color. And if they’ve got the imagination, it’s just as complex as a guitar solo. And it’s beautiful. So we have a very good show. We’ve also got a new album coming out. Just signed a new record deal. I can’t reveal yet who the company is, but that’s the new album coming out next year.

LeValley: And this song “Zombie Yelp” will be on it, I assume?

Brown: Oh, no, no, it’s a different record company. With Cleopatra, I’ve just done the pieces of work with Alan Davey and the one of which is the album and the other is the solo track. Oh, except that I think we added another guest performance with… There are some people who got together to do a tribute to Emerson, Lake, Palmer. And I did the song, (sings) “Welcome back, my friends, to the show that never ends. I’m so glad you could attend. Come inside, come inside.” And I did that with Carl Palmer’s ELP Legacy on the last big tour.

LeValley: Right. Carl Palmer was in your original band, right?

Brown: He was, yeah. After Drachen Theaker, Carl came in and it was he who was on the video as the drummer. And he was with The Crazy World for about a year and a half before he and Vincent went and formed Atomic Rooster. And they got three Top 10 hits, too.

LeValley: They must have been UK hits. I don’t think they ever had any kind of commercial success in the US.

Brown: No, it was U.K. I’m not sure what the problem was with the States, but something.

LeValley: So I didn’t know about the new album. Do you plan on touring when things settle down?

Brown: When things get back to the place where we could actually sit near each other. (Someone speaks in the background) That voice in the background is my partner and manager Claire…Claire Weller, who also was the guiding person for this show that we do. And she’s the creative director of our stage show. And also the new album. She’s the creative director of the new album we’re going to do now. Also, I’ve just done, I’ll fill you in because it’s a time when I’m busier than I’ve been just about the whole of my life, I think. But it’s all different things going on. We just about eight weeks ago put out a charity single. It was the idea of Ian Grant and Paul Mitchell, and it was to help raise money for musicians. Because particularly in England, the government helps classical musicians but normal, everyday, uh, popular musicians, no. So we just wanted to try and raise some money. So we put out a version of House of the Rising Sun with a stellar collection of musicians, one of whom was, for a while, in The Crazy World. It’s had a lot of good interest. So we’re about to put out another one. Which again, I can’t say anything about. (Laughs) And it’s just to keep the idea, you know, going that maybe something should be done about musicians. See, the English government guy said, “Well, when it comes down to those musicians, they should all retrain in another industry. That’s not a real job. I think you should go and get a real job.”

Brown: Finally I’m doing another single. This one is with a Peruvian band. Claire came across this piece of music on the internet and she said, “Listen to this”, and it was a band with this amazing flute player, so she wrote to the band and said, “We really like your music.”

Claire Waller: No, actually, they were going to play New Day this year. We were going to play together.

Brown: Yeah. And they were booked for the New Day Festival in England, which we’re also playing. And so it ended up the manager of that band got in touch and said, “Well, we’re doing this new single. Would you listen to it and tell us what you think?” So we did. And they used that on the publicity for their new single. So that was good. That was nice. And then they said, “Well, that was really good. And the guy who’s producing the album, Roy Z, works with Bruce Dickinson, he’s got a track that he originally wrote for you to sing on a Bruce Dickinson album, but in the end, what they had that was a little, you know, to have suddenly a guest artist doing the main song on that album would have overbalanced the album so they didn’t use it. So the Peruvian band, they’re called Flor De Loto, they recorded the backing track for it being produced by Roy, who wrote it. And so now I’ve written the lyrics for it and we’re recording it and that’ll come out soon.

LeValley: And this is with the Peruvian band?

Brown: Yes.

LeValley: OK. Is it like traditional Peruvian music or is it more like rock and roll?

Brown: Well, the flute player, for instance, is of the original indigenous tribes from Peru, and he plays the traditional flute more in the realm of the way that, say, Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull. In that feel rather than just playing a traditional style of music. But this guy is the leading flute player of that tribe of people, that whole mast of the original inhabitants. He’s regarded as their best player. So he’s a member of the band and they play prog music based on heavy metal, and obviously a touch of world music.

LeValley: Ok, that hasn’t been released yet, right?

Brown: No, it isn’t finished yet. (Turns to Claire) When will that be released?

Claire Waller: I think probably about a month.

Brown: Yeah, that will probably come out in about a month.

LeValley: Ok, well, I want to thank you for taking the time to speak with me today or tonight. I guess it’s night over there. It’s really an honor.

Brown: Well, it’s a great pleasure to do it.

This article originally appeared in It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine on December 6th, 2020.

Jeannie Powers

Gallery

Recent Articles

Podcast–Alex Detmering

•

March 4, 2026

The Circle is Red by White Noise Sound–Album Review

•

March 2, 2026

Loading...