Interview: Rod Argent

Interview: Rod Argent

Jason LeValley:

It’s nice to meet you. I’m Jason. Hello.

Rod Argent:

Hi, Jason. Nice to meet you.

LeValley:

You had a birthday yesterday. Happy birthday!

Argent:

Thank you so much. Not that I wanted another one, but I did.

LeValley:

Did you do anything to celebrate?

Argent:

Not really. We had an easy day just trying to get things ready to go away on the tour. It was a gorgeous day here, so my wife and I just stayed around where we live. And there’s some lovely ground around here, so it was very pleasant.

LeValley:

That’s great. Well, I’m a big Zombies fan, so it’s really an honor to meet you.

Argent:

Thank you so much.

LeValley:

So not many people realize how young you guys were when the band formed. I think you were just 16, and by the time you were 19, you had a hit song with “Tell Her No”.

Argent:

Do you know what? Yes, 16. You’re absolutely right. No. By the time we’re 19, we had a hit song. “She’s Not There”.

LeValley:

Oh. “She’s Not There”. OK. Have you been a musician your entire adult life?

Argent:

I have, yeah, absolutely. And it was a dream of mine. It’s what I really wanted to do. So I’m so happy that it turned out that way.

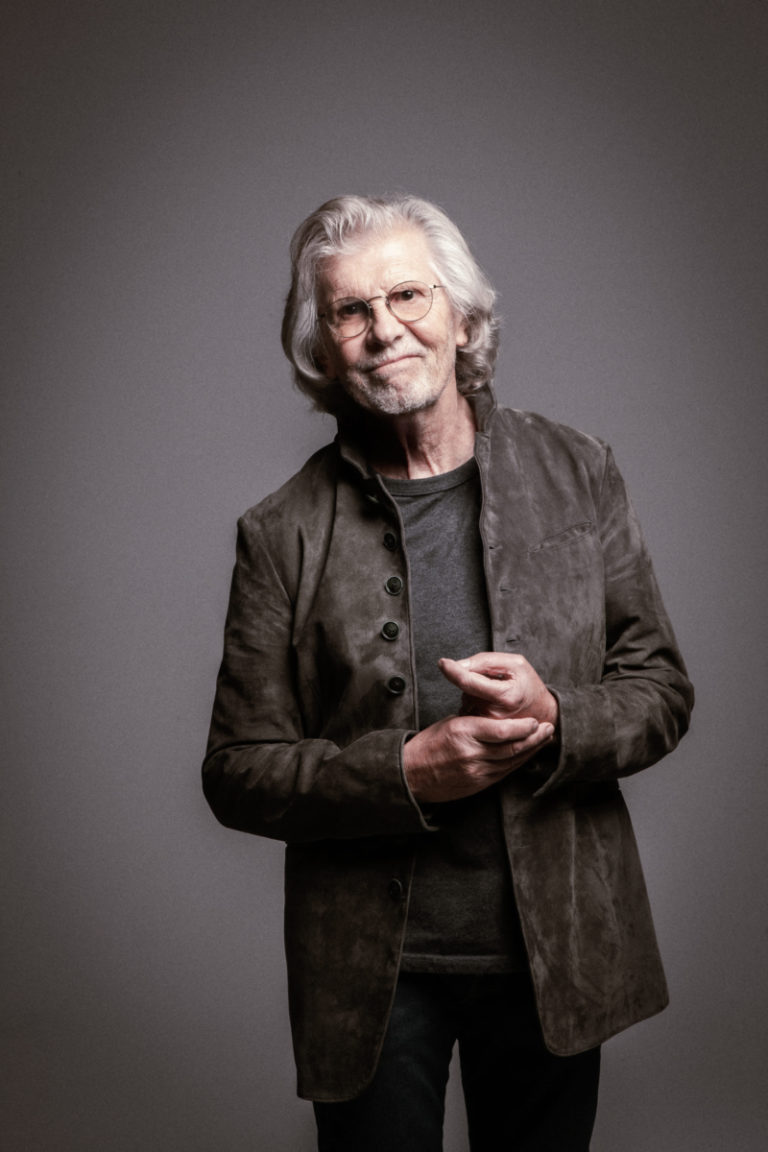

Alex Lake

LeValley:

That’s great. The Zombies discography is a little bit confusing to me. It seems like most of the British Invasion bands were cranking out a couple of full-lengths a year. And you guys released Begin Here in 1965. Then you contributed songs to a soundtrack, Bunny Lake is Missing. And then you released your magnum opus, Oddessey and Oracle in 1968. What kept you guys from being more prolific?

Argent:

One of the reasons was the fact that we had a very autocratic producer who was a great musician, a lovely guy, but he was from a previous era, a really previous generation. And he did a great job on the first session that we ever did, which is one of the first songs I’d written “She’s Not There” and Chris White. So I wrote a song for the session. Chris White wrote a song for the session, and actually, I wrote another song, which I already had, which was the first song I’d ever written, called “It’s All Right With Me”. And then we did “Summertime”, and after that, instead of just approaching the material that we were bringing along to the sessions, Ken Jones, our producer, was, rather than just approaching it as let’s make the best out of this and just see what it is and see how we can get the best out of it in the most authentic way that the band wants it. He was trying to analyze what made the first record hit, and so in his head, he thought, right. Well, Colin’s voice was fairly breathy on that record. So we’ve got to exaggerate that and there were other elements like that going on and it started to drive us mad because we always had really great ideas about harmonies and how full the harmonies should be.

We had ideas about the grooves that we were playing and how they should be slightly more modern from a sound point of view at that point. And we just got very frustrated. And when it appeared, and then in the UK, we only ever had one hit single at that point. “Tell Her No” wasn’t a hit. It was in many other places in the world, but it wasn’t in the UK, and we really suffered from that. And because in those days the world was so much a bigger place and people traveled so much less and you didn’t really know what was going on in the other parts of the world. I mean, many years later we found out we almost always had a hit somewhere in the world, but we just didn’t know that at that time. So when we recorded a record, I always remember when we did “Is This the Dream?” It sounded so stonking when we recorded it. It was really muscular and our producer wouldn’t let us stay for the mix. He would never let us. We had to go away and he would do it in a couple of hours. So we’d go away for a couple of hours.

We always had really great ideas about harmonies and how full the harmonies should be.

We come back and I remember Colin saying, “Is that the track we recorded, is that the one we actually played?” It was so frustrating for us. So when it got to the point where, because of the lack of success in the UK, we thought that we might possibly split up. Chris White and I said to each other, “Listen, if the band splits up, we have to at least make one album and we have to try and produce ourselves”. It’s not something we’d ever done, but we at least wanted to have a go at it and we got a deal to do Oddessey and Oracle. We weren’t given very much money to do it, but we really hit it with enthusiasm and we were knocked out because we at least felt that we were getting on tape, as it was in those days, the construction and the sound that we wanted out of the music that we were trying to make and the actual perspective of the harmonies, one thing or another. So we were like kids in a candy store. And at the end of the record we felt it was the best we could do.

And we thought, well, a couple of the guys had said things– like our guitar player saying, “Look, guys, I’m getting married; I’ve got no money”. Because the other part of the equation was that we were ripped off very badly by sort of some management and agency considerations. We found that at the end of three years and where we had several big hits around the world and we were headlining tours. We never did anything more and break even from a live point of view. So we had a situation where Chris and I, as writers, because we had very honest publishers, they would pay us what we were due and we were absolutely fine for money. But the other guys in the band were just getting by on the shoe string, which was a crazy situation. So the band split up. We were still very much friends with each other, but we split up and we thought we’d give one single, we bring one single out. And the first single was in the UK with “Care of Cell 44” and it wasn’t a hit. So we broke up and then we moved on to other things. Chris and I formed a partnership, a production partnership.

Alex Lake

I started to form Argent, my second band. Chris was a sort of silent member of Argent. Chris White, our bass player. And he was producing and co-writing with me for Argent when we almost got the band together suddenly, because Al Kooper, who was a really hot producer at that time, had just signed a deal with CBS in America and he was sent over by clients over to the UK to find some great records. And he bought 200 records and he went back with 200 albums. And he said to Clive Davis, there’s only one album that whoever has got this, you have to release it, you have to buy it, whoever’s got it. And Clive said, “Well, we own it”. He said, “But we’ve passed on it because we don’t think it’s commercial”. So Al said, “You’ve got to release it”. So Clive agreed. He put out a single of his choice, which was also “Care of Cell 44”, which did nothing in the States. He then put out a track on Odessey and Oracle, which I absolutely love. It’s a Chris White song. It’s never a single in a million years. It was “Butcher’s Town”. And then Clive Davis said, “Well, we’ve given it a go and that’s enough for us, really”.

And then one guy, one DJ in Idaho, in Boise, Idaho, started playing the record and it would not die.

And Al said, “Listen! You’ve got to listen to me for one record. You’ve got to put out “Time of the Season”. And Clive Davis said, “Well, I’m not sure that’s commercial:, but he (Al Kooper) said, “Well, will you put it out?” So they put it out for a few months. Nothing happened. And then one guy, one DJ in Idaho, in Boise, Idaho, started playing the record and it would not die. He started to play it and it started to really spread out in ripples and people started to lock onto it. And then suddenly it took off like wildfire and it ended up being number one in Cash Box. And I think it was number two or number three in Billboard. And it was number one in Cash Box on the very day, 50 years to the absolute day that the Zombies were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. So that was a strange coincidence of dates as well.

LeValley:

Yeah. Well, it’s a great song. It’s just fantastic.

Argent:

Thank you.

LeValley:

Yeah. And Congratulations on finally getting inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Argent:

Thank you.

LeValley:

I mentioned the soundtrack, Bunny Lake Is Missing. What made you decide to do that soundtrack?

Argent:

Well, we were offered it in the sense that Otto Preminger was auditioning several bands and it was a club in London, a fashionable club called Cromwellian Club. And we came along and we set up and we actually played “Summertime”, which was a song we’d always played and even do today sometimes. And it turned out that Otto Preminger used to be a friend of George Gershwin. He actually knew him in his young days and he was knocked out with our version, I’m very pleased to say, when we did it live and he said, “Okay, you’ve got the gig, but I need three new songs and I need them within three weeks” or something like that. And I didn’t have anything. But Chris White was working on two or three songs. Colin wrote, I think, just about the first song he had ever written. And Chris wrote another two songs and they became the three songs in Bunny Lake Is Missing. And we were actually given star billing, even though we were only onscreen for about 45 seconds with Lawrence Olivier, which is really crazy.

LeValley:

You mentioned Chris White, that he contributed to Argent. Why wasn’t he just in the band?

Argent:

He didn’t want to play anymore at that point. He wanted to stay in music, as I absolutely did in one way or another. And I wanted to continue playing. And I formed the band with… The other founder member was actually Jim Rodford, the guy who later became a founder member, with me, of Argent. And then after that for 15 years on their biggest ever selling singles, for instance, and records. He was basically with The Kinks. And Unfortunately, Jim very sadly passed away recently. But he was my cousin and he was the guy that turned me onto rock and roll in the first place, actually. Chris White loved Jim’s playing and he said, “No, Jim is the man for you”, but he wanted to stay producing, writing, and that’s what he did basically at that point, right?

LeValley:

Yeah. I remember Jim Rodford as a member of The Kinks, and I did see him, I think, with you and Colin in like 2013, maybe? Around that time period. Did you, since he was in The Kinks, did you develop a relationship with the Davies Brothers or any members of that band?

Argent:

No. I mean, I’ve met Ray. I don’t think I’ve even met Dave. I’ve met Ray a few times and he’s always been very nice. But no, I didn’t have any relationship with them. Obviously, Jim got close with them. He was just working with them all the time.

Alex Lake

LeValley:

Okay. So Oddessey and Oracle is considered a psychedelic pop classic. Were you guys experimenting with psychedelic drugs at the time?

Argent:

No. I mean, I personally was never interested in trying to take drugs. It all seems a bit crude to me. It seemed like a way of getting an effect, almost like if you’ve got a computer and you throw a spanner into it, you can get a dramatic effect. But it’s not one that’s sort of subtle or interesting or…well, it might be interesting, but it’s not one that is detailed enough for me. It comes with all sorts of dangers. I always felt that and I was never tempted to that. I’ve got nothing against people that did. I didn’t have that sort of penalistic attitude, but at the same time, it wasn’t for me.

LeValley:

Okay, so what about other members?

Argent:

No. Nobody else. Nobody took anything psychedelic. Absolutely.

No, I was saying over the years, a couple of the members of the band sort of dabbled in smoking a little bit, but that’s as far as it went, and that wasn’t a frequent experience for them. They just did it very occasionally. And I don’t know if anyone ever took some cocaine. It’s not something that actually appealed to me ever. And as I say, I didn’t condemn anybody that did, but it was just not for me.

LeValley:

Right. It’s just interesting that this psychedelic pop classic wasn’t actually influenced by psychedelic drugs.

Argent:

No, but it’s very interesting, isn’t it? I mean, when you hear like “A Day in the Life”, some of the interpretation of the lyrics in that were very psychedelic and, in fact, “Went upstairs and had a smoke, somebody spoke and I went into a dream”. McCartney said, “That’s exactly what I meant. He said it’s no more than that”. And it’s like “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds”– written about Julian Lennon and one of his drawings that Lennon loved. And yet people would always put that meaning and an interpretation on those things. I’m not saying they didn’t make any drug references. Of course they did. But I always found it very interesting that the way they first got turned on to psychedelic drugs was because their dentist put it into something unknown to them. They just had their first trip and they didn’t know what was going on, but I know some people have found it really revelatory, but other people, it’s just been so sad the way it seems to have affected Peter Green and Brian Wilson, et cetera. I find that very sad.

LeValley:

Yeah, I do, too. I do think, though, that the drugs just exacerbated a pre-existing mental condition.

Argent:

I think you’re very right. And I think sometimes people, if they’ve got an existing condition, start to self-medicate anyway by using drugs, and that can lead to a result that nobody wants.

LeValley:

Right. So I understand that you and Colin both moved to the US at some point. What prompted your move?

Argent:

I never moved to the US. Colin did.

LeValley:

You didn’t?

Argent:

Yeah. Colin was there for at least six months because he signed to Rocket Records and Elton John wanted him to…I think that was the beginning of Colin’s stay in the US, wanted him to record over there and to immerse himself in the American lifestyle. So I think that was the initial reason for that. Also, by that time, I was married. Yeah. By the time Colin went over, I got married in 1972. And in fact, my wife and I just had our 50th anniversary this year. So that was one reason why I felt more of a stable connection to the UK and didn’t really want to move abroad at that point.

LeValley:

I see. Okay, well, I read somewhere that you had both relocated to the US, and obviously that was a bad source.

Argent:

Yeah.

LeValley:

Are you a fan of any newer bands? And if so, who would they be?

Argent:

Probably because of my advanced age, I really don’t listen to an awful lot of new music. A lot of new music I find a bit mechanical and a bit uninventive. But there’s one California band, The Lemon Twigs, that I really liked, actually, particularly their first album. I think it was their first album anyway, but I remember liking that lot at the time. But I’m not really okay with much modern music, actually, to be quite honest. For me, the older stuff was very in those days, to make something work, you had to have a chord sequence which really worked and was effective, and you had to have some playing on a groove that was really effective, that wasn’t sampled or wasn’t using everything that’s possible to use now. These days, you can actually just sample a drum loop and a bass loop and just throw a few seconds of a vocal sample on there and you’ve got something that sounds almost like a hit record immediately. In those days, there was only one way to connect musically and that was to get something that really structurally worked. I mean, there was no other way of doing it in those days.

It has meant that many years later there’s a generation of people that actually tune in and relate to what we did back then, and that’s really gratifying.

And I think you ended up, at least in my old fashioned way of listening to things, you ended up with something that was more creative, more structured, and more lasting. And one of the things that really knocks me out and that was unlooked for, really, is the fact that even with Odyssey and Oracle, we almost always have a young component in the audience. I’m not saying we’ve got a young audience all the time. Of course we don’t. We have people of all ages, but there’s almost always a young component that really reacts and sends back a lot of energy from offstage and, in some way or other, relates to what we were doing all those years ago. And the new stuff that we do now, they really relate to it. And that was so unlooked for and it was so gratifying. And I think that is the result of having to work in such a structured way and in the old days, we would never make a record that was very much like saying, “Oh, we have to get to the hook in 30 seconds, otherwise it won’t be commercial”. We never thought like that. We always try to write something which turned ourselves on to a certain degree with the thought that if you could end up with something that actually works for yourself, you stand a chance of reaching out and touching other people.

And in the short term, it was often less commercial for us instantly, but I think it has meant that many years later there’s a generation of people that actually, somehow, tune in and relate to what we did even back then and that’s really gratifying and it was certainly not something we expected to happen at all.

LeValley:

That’s great. Your publicist wanted me to keep this short so, out of respect, I will wrap this up. I do plan to be at your show in Tucson. Just got my tickets yesterday.

Argent:

Cool.

LeValley:

Yeah, I’m looking forward to it.

Argent:

Excellent. Well, I hope you enjoy it.

LeValley:

Thank you. Nice talking to you.

Argent:

Lovely to talk to you, Jason.

LeValley:

I really appreciate your time.

Argent:

Great pleasure.

LeValley:

All right. Take care.

Argent:

Cheers, man. Bye.

The Top 100 Psychedelic Rock Artists of All Time

The 100 Best Psychedelic Rock Albums of the Golden Age

The Top 200 Psychedelic Songs from the Original Psychedelic Era

Interview with Colin Blunstone of The Zombies

The Psych Ward: Oddessey and Oracle

Gallery

Recent Articles

Can Molly Mend Your Marriage?

•

February 16, 2026

Immer Für Immer by Flying Moon in Space–Album Review

•

February 13, 2026

Loading...