Interview: John Densmore

Interview: John Densmore

John Densmore:

Hi, Jason. Nice to meet you.

Jason LeValley of Psychedelic Scene:

Yeah, well, we actually met in 2013 when you were on your book tour.

Densmore:

Oh.

LeValley:

But nice to see you again and thank you so much for taking the time to do this.

So you and Robby Krieger played together in a band before the formation of The Doors. And the name of that band was the Psychedelic Rangers. Was it a psychedelic rock band?

Densmore:

The four of us were then taking legal LSD.

LeValley:

Right. It wasn’t made illegal until 1966.

Densmore:

Yeah, this was ‘64-’65, and we didn’t play any gigs or anything. We had, like, one or two songs. The main song was called “Paranoia” (laughs) about the police. Back then, smoking a joint in the car was just like terrifying because pot was linked to heroin. What’s it called? Stage one or something? Back then we thought, in a couple of years, pot will be legal. Hello? 40, 50 years later, finally, you know, boy, is progress slow. And speaking of LSD, as you probably know, there’s a bunch of tests with very organized, controlled imbibing of LSD at Harvard and Med School or whatever. And it’s really helpful to PTSD and terminal cancer patients who… it certainly is intense. And so you get a little death before the big death and then the big death. Like the terminal patients aren’t so scared.

LeValley:

Right.

There was a terrible knee-jerk reaction to psychedelics.

Densmore:

It’s a good thing. But back in the day, Tim Leary, I love him, but he was over the top, you know? He wanted to put it in the drinking water. There’s a wonderful, very informative show on Netflix by Michael Pollard called How You Can Change Your Mind.

LeValley:

How to Change Your Mind, right? And that’s based on his book How to Change Your Mind.

Densmore:

Right.

LeValley:

So it’s kind of ironic that this drug LSD that was so, so frightening to so many people and linked with the Manson family and just people jumping out of windows and all this crazy stuff is actually something that is helpful for the brain and has medicinal value in terms of treating PTSD, depression, and so forth.

Densmore:

It’s pretty interesting. It seems like wherever there’s some knowledge to be gained, right nearby is danger. So around the peyote button is strychnine. You have to take that stuff off before you make your tea. So, yeah, there will be Manson, there will be Art Linkletter’s daughter falling out of a tree, but that is not metaphoric for the whole thing. Maybe the corona vaccine is a good example. Yeah, there’s problems, whatever it is, one in a million or whatever, but overall it’s a good thing. So there was a terrible knee-jerk reaction to psychedelics. It’s interesting. I took LSD, still legal. I’d never smoked pot, but somehow I knew that your environment is really important because it just, you know, psychedelics, it just amplifies what you got going on.

LeValley:

Sure.

Densmore:

So I was out in a beautiful canyon in Southern California and yeah, the first five minutes of my first LSD trip, I was terrified. I was looking into the void or whatever the hell. And then my friend who, my best friend who took the trip with me started laughing, which brought me out of it. I started laughing and then I saw God in every leaf for the next 8 hours and it jump-started my entire spiritual life and it was really a good thing. I think Ram Das, right?

LeValley:

Richard Alpert.

Densmore:

Yeah.

Him or one of those Mayor Baba, one of them said, “Hey, psychedelics open the door to spirituality now. That’s great. Now close it!” Robby Krieger and I took LSD a few times. I mean, the word bummer was not even in my vocabulary until Art Linkletter’s daughter had her tragedy. And then I stopped taking LSD and Robby and I thought, “Well, okay, meditation is another way to open your consciousness. Certainly not, as I got quite much more of an impact from a tab of acid than the communion wafer from Catholic church. So Robby and I went to Maharishi’s meditation. Now, this is a year before the Beatles or whatever.

LeValley:

Oh, you went to India?

Densmore:

No, he was here in LA. And we went to a little meeting– 30 people in a little room– and in walks this man, or saint–whatever you want. He’s all in white, bearded, and the love vibe is just palpable. And I’m thinking, man, this is different from the priests, and they’re black and they’re collars and telling me I’m a sinner and all that. So I’ve been sucking up Indian meditation and culture ever since. And Maharishi coming. Actually, Paramahansa Yogananda was the first Indian guru who came to the States. He came to LA in the 50s. All of us, the Beatles. There was no internet, but somehow these archetypal union undercurrents were going on. During that time, all of us were taking LSD, all of us were reading Autobiography of a Yogi by Yogananda. And Maharishi coming really jump-started all of us looking into Indian culture and that’s Robby Krieger and I joined Ravi Shankar Kanara School of Indian Music in LA and George Harrison dipped Beatles songs in curry sauce. And Bollywood is still reverberating, so I don’t know, I’ve kind of gone off on a thing here. What was your question? (laughs)

LeValley:

It’s okay. Yeah, since you had that experience, it’s kind of interesting that Indian music didn’t turn up in The Doors music.

Densmore:

Oh, but it did, Jason.

LeValley:

Well, I can’t think of a song with sitar.

Densmore:

No, it’s not literal, Jason. I have a big jazz background. I don’t play jazz in The Doors, but I’m influenced by the improvisation. And I actually stole some great little jazz drum licks that are in Doors songs. So Robby Krieger tuned his guitar to sort of an open sitar tuning for “The End”, and most songs were three minutes. And we started writing “The End”, which was ten minutes. And “When the Music’s Over” 10-15 minutes, “Light My Fire” was six minutes instead of three. We thought Indian ragas are just…they go on. At one meeting with Ravi Shankar, he gave a talk to the class. He said something like, “the Western world is too eager for a climax. Take your time”. And so ragas have ten minutes of foreplay before you get off. And we took that in.

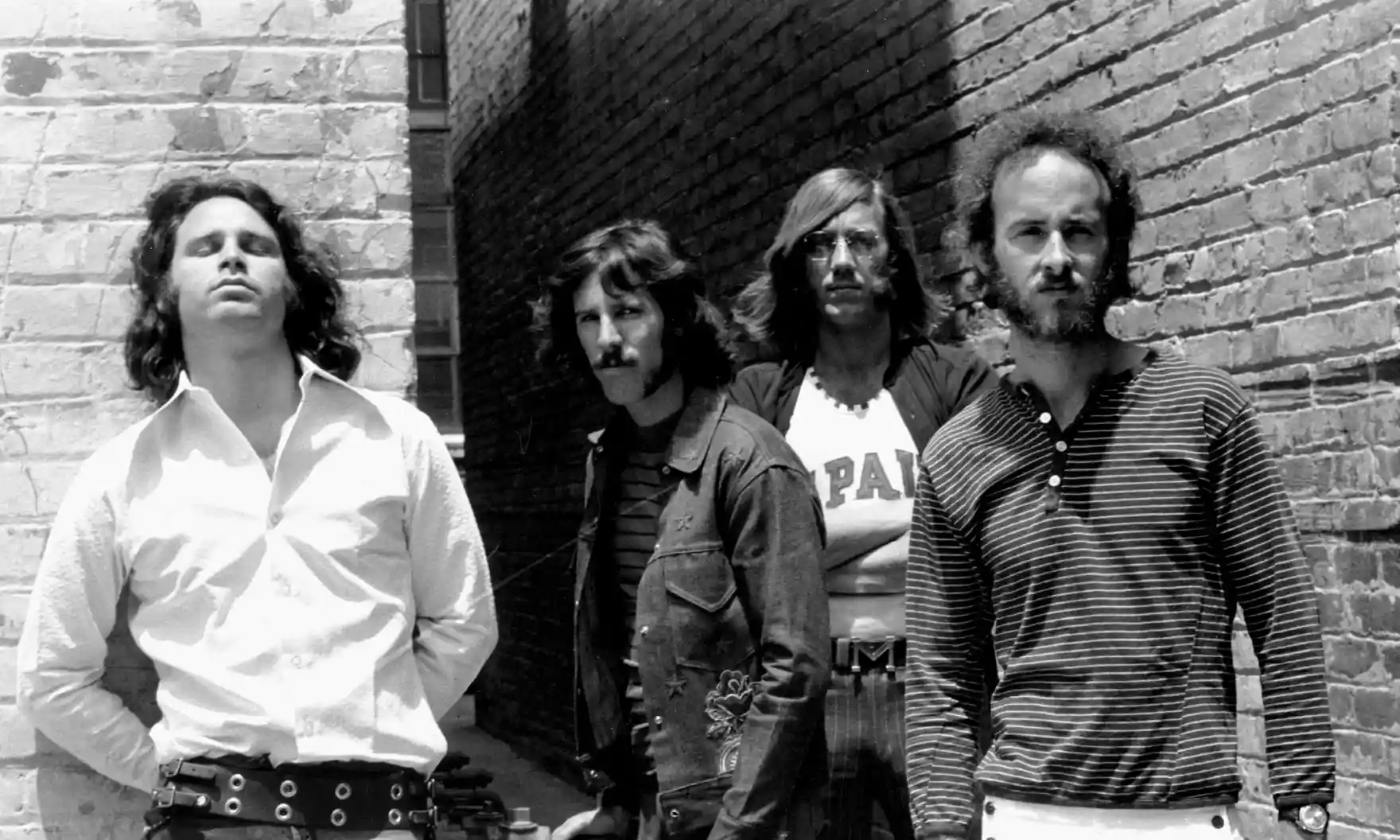

photo by Carlos Chavez

LeValley:

Right.

Well, you guys were really young in 1964, like, you would have been 17, I think, or 16.

Densmore:

17-18, yeah.

LeValley:

Wow.

So what kind of music was it in The Psychedelic Rangers?

Densmore:

Silly. It wasn’t even…

LeValley:

Okay, that was just the name of the band. But you actually were already experimenting with LSD?

Densmore:

The four of us took LSD together. So we called ourselves the Psychedelic Rangers. And then we started playing a little music. We weren’t officially a band, but yeah.

I knew something was off, something was stretched out. Yeah. Jim was looking at a moth on stage.

LeValley:

So did you continue using psychedelic drugs when you were in The Doors?

Densmore:

No.

Jim took it on stage at the Hollywood Bowl without telling us. Thanks a lot. Somehow he managed to get through the performance. But between you and me, Jason, and the listeners out there, who’re going to hear this. I was playing really strong because I knew something was off, something was stretched out. Yeah. Jim was looking at a moth on stage. Hey, man, there was 18,000 people out there. I mean, he was fine somehow. Maybe he peaked after the show was over. But in rehearsals, before we ever got a gig we were still taking legal LSD and sharing our experiences with each other when we got together to rehearse.

LeValley:

But you and the other three members of The Doors never took LSD together?

Densmore:

Contrary to the Oliver Stone movie, no. No disrespect. I like that movie. Ray hated it. But Ray went to film school and wanted to be a director. Jealousy abounds. You take a six year career and cram it into a couple hours, you have to edit. So he had us all together in the desert taking acid. Not true. But we were taking acid individually. So, you know, it’s poetic license.

LeValley:

Yeah. I actually don’t remember that scene. I did see the movie, but that was 30 years ago.

Densmore:

Yeah.

LeValley:

How about in more recent years? Have you continued to explore psychedelics?

Densmore:

I mean, I am intrigued by all this stuff that’s coming up–ayahuasca and ecstasy. Haven’t gone down that road. I smoke pot occasionally. I like a glass of wine.

LeValley:

Well, you alluded to some significant experiences when you were younger on LSD and I just thought, maybe at some point…

Densmore:

Will I go down the Aldous Huxley road?

LeValley:

Well, maybe, yeah. You’re talking about taking acid on your deathbed?

Densmore:

Exactly.

Eagle Rock Entertainment

LeValley:

Yeah.

Densmore:

Oh, my God. Can you imagine this brilliant English writer in a three-piece tweed suit getting infatuated with the weave of the tweed? I loved it that he was open to that and it’s pretty wild to take it on the way out.

LeValley:

Yeah. I would think that just the experience of dying would be enough. Anyway, you mentioned your jazz background. You’ve cited Elvin Jones, John Coltrane’s drummer, as being an influence. And then in somewhat more recent years, you had a jazz band, Tribaljazz. Is jazz your go to listening or is it more rock or something else?

Densmore:

Jazz is the thread of my youth and I go back to it now and then. I like everything. I like world music. I like listening to music that is in a language I don’t understand because even if you literally can’t get what they’re saying, you get a feeling for the culture.

Hang on. All right, this is now turned into an infomercial. (Holds up book) You know about this? Came out, I don’t know, a year ago during the pandemic. The Seekers. My third book. And I go on and on about sound and silence.

I lost my thread. I must be on acid. What were you asking?

LeValley:

I was about to ask a question about jazz. Now I forgot.

Densmore:

Yeah. So in this book, it’s my tip of the hat to various artists who have fed me. One chapter is on Elvin Jones and how I was a teenager when I stumbled into seeing John Coltrane. I didn’t know he was going to be that giant of an icon, but I sent some kind of magic, something really unique and new going on. And so the way Elvin played with Coltrane influenced the way I played with Jim.

LeValley:

So you saw Coltrane live?

Densmore:

Oh, yeah. Many times. I got to send you this book.

LeValley:

I’d love to read it.

I like listening to music that is in a language I don’t understand because even if you literally can’t get what they’re saying, you get a feeling for the culture.

Densmore:

The first and most important job of a drummer is the pulse. Once you start, if it’s a ballad, it’s a slow pulse. If it’s salsa, it’s fast. But you have to keep this steady pulse. The first drum beat we all heard was in the womb. It’s our mother. And in music, if it’s an ensemble or a duet or a 40 piece orchestra, you have to try and play as one. You have to try and get back to that heartbeat in the womb. That’s what makes everybody feel good. So Elvin had this wonderful pulse, but he played around it constant, what critics called polyrhythms. And I just ate that up and I’d go home and copy him for days. And so I knew I had to keep the pulse with Jim, but I could play off of him. I could have a little conversation with him while still having the internal pulse. Therefore, the polyrhythms fit. Some critics used to say that Elvin sounded like he was going to fall into his drum set. It’s very true, because he was so loose with all this stuff. But there was an internal metronome that was just there.

The pocket is everything to a musician. Thelonious Monk, incredible jazz pianist, composer. He had a list of ten suggestions for musicians. The very first suggestion was that a musician has to have a good sense of time, especially if he’s not the drummer. Oh, my God. That’s genius. It’s saying that you got a sax solo going. If he doesn’t have an internal groove of where the song started, all that pyrotechnical stuff won’t…Nobody will care. Nobody cares. So, as in Native American music, the grandfather beat the big bass drum. Without that, all the flashy shit doesn’t matter. And now that I’m… fucking, what am I, 78 in a few months? I don’t have the chops. I don’t play that much, but I don’t have the chops I used to. But I have learned that if I put a cymbal crash– (turns around and tries to hit cymbal) can’t reach it– in the right spot, it’s as good as the fancy technical stuff I did in my youth, because it’s musical, and there’s the internal pulse for the whole composition. Boy, am I waxing a lot.

LeValley:

That’s okay. It’s great.

You mentioned that you don’t have the chops that you used to. Is that…

Densmore:

I don’t have– I don’t have what?

LeValley:

You said something like you don’t have the chops that you used to.

Densmore:

Oh, chops, yeah. Technique.

LeValley:

Right.

So have you found that aging has affected your ability to play the drums?

Densmore:

Oh, a little bit. I play hand drums more than the kit. It’s easier on my body. And I used to blame it on Robby, the guitar player. I got tinnitus–ringing in the ears, but then I realized it was my cymbals– crashing those cymbals, and I was going nuts. When I first got I was like, “Wait a minute, I’m a musician. This is my entire life, and I’m having ear problems?” And then that kind of got me into writing books, and I’m real into that. It’s not as fun as playing music with other musicians, but it’s another creative outlet that I really worked on for years and years, and I get off on it almost as much as music. And that’s why I took this tough circumstance of ear stuff and turned it into okay, that’s the message I’m supposed to write. I’ll still play a little, and the tinnitus is much better because I’m very careful. We didn’t have earplugs back in the day. We didn’t know what we were doing. Yeah.

Estate of Edmund Teske/Getty Images

LeValley:

Do you have to wear hearing aids now?

Densmore:

No.

LeValley:

That’s kind of surprising.

Densmore:

What, Jason? (doing impression of hearing impaired old man) My hearing is good. I mean, I haven’t had it tested in a few years, so it’s probably not as good because of my age, but I had it tested right after I realized I had the ringing. And they said, “Your hearing is good. You just have the ringing”. I did have the sense to always have my drums kind of parallel or behind the amplifier lineup. I was not in front of them.

LeValley:

Are there any current artists that you really like– jazz, rock, or otherwise, artists that have come out in, say, the last ten years?

Densmore:

Yeah, but I can’t think of any. I just don’t have my finger on the pulse of what’s going on in the current scene.

LeValley:

Right.

Densmore:

Okay. Now I’ll say some names. Who’s that guy? Nathaniel Radcliffe.

LeValley:

I’ve heard that name. I’m not sure who that is.

Densmore:

Jason, come on, get with it. He’s playing the Hollywood Bowl tonight. Willie Nelson.

LeValley:

Willie Nelson?

Densmore:

Yeah, he wrote a song–”Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die”

LeValley:

Yes, I’ve heard of that.

Densmore:

He’s a mentor because he’s 89 years old and still doing it.

LeValley:

Yeah, pretty amazing. You say you like to write, and you’ve written and published three books. Do you have anything else in the works?

I think the message is that Gaia, the earth, she’s had our foot on her. With the pandemic, she just snipped a toe off to wake us up.

Densmore:

Well, I’ve been working on a script for 100 years, so I can be like every waiter in my hometown. That’s circulating around a little bit now. I had a jam session with a percussionist friend of mine and he went and turned his phone on this record button on his little phone, and something turned out so good. I had Robby overdub some reggae guitar, and I had some lyrics that I wrote years ago. I needed more, but this inspired me to write more. And I thought, well, you know, Bob Dylan can’t sing, so I can. And so I have a single which will be coming out. And I did a video, too. Ashley– I hired this wonderful woman in Bogota, Colombia, because it’s a global web village now. And so this will be coming out, I don’t know, the next month or two maybe. I’ll donate half the dough, if there is any, to fighting the rain forest fight or something, because that’s what it’s about. It’s about indigenous cultures.

LeValley:

Okay, well, I look forward to hearing that. What do you hope to accomplish in your remaining years?

Densmore:

(Laughs) To keep breathing.

It’s interesting. The pandemic certainly changed things. No disrespect to all the tragedy, but I think the message is that Gaia, the earth, she’s had our foot on her, and she did. With the pandemic, she just snipped a toe off to wake us up. And the greenhouse gases did go down at the beginning of the pandemic when nobody was going anywhere. And I used to go to Hawaii every year, and I haven’t been there in three years. And then I have a beautiful garden out that window. I think the message for me is to smell the roses. I appreciate what’s going on, so I’m appreciating. I just have gratitude for what looks like little things, but as Coleman Barks, the great translator of Rumi, said, “the microcosm, your inner, is bigger than the macrocosm, the outer”.

Put that in your quantum pipe and smoke it.

LeValley:

I will.

What musical moment in your career fills you with the most pride and joy?

Densmore:

Wow. Nice. Well, lots of them. But when we were recording, I knew. I sensed, oh, there’s something good. These songs, man. Jim’s words were so poetic, and it was great fun to play giant concerts and be worshiped by thousands. But really the most exciting was the move from clubs to maybe opening act in a small concert hall. It meant that the train was leaving the station. We are going to make a living at this. Okay. Whoa. And here I am with gray hair and still talking about this friggin’ band. But I guess something transpired–some gift from the muse. Either that or it’s just the drumming. (laughs)

LeValley:

The drumming in general?

Densmore:

That made it all happen. That was it. A bad joke.

LeValley:

So no particular moment that you can really hone in on?

Densmore:

You want me to nail down our six-year career to one (ahh)?

LeValley:

If you can’t think of anything, that’s okay. I just thought I’d throw that out there and see if there was anything that really stuck out.

Densmore:

Nothing. I was thinking of when we recorded “When the Music’s Over”, which I had a conversation with Jim on that one in the middle. There must be some other concerts. We played the Round House in England with the Jefferson Airplane. “The West Coast psychedelic sound goes to England.” And McCartney was in the audience and we played real good. We’d go to San Francisco and flower power and we’d play “The End”. And everybody’d be real quiet and scared. Maybe you get a stronger impact if they go home and chew on it rather than dissipate it all in giant applause.

LeValley:

Right on.

Densmore:

Yeah.

LeValley:

Well, John, I’m going to have to wrap this up.

Densmore:

I’m about spent.

LeValley:

Okay, great.

Densmore:

Well, thanks again and send me a link.

LeValley:

All right, thanks so much.

Related: The Top 100 Psychedelic Rock Artists of All Time

The Top 200 Psychedelic Songs of the Original Psychedelic Era

Gallery

Recent Articles

Can Molly Mend Your Marriage?

•

February 16, 2026

Immer Für Immer by Flying Moon in Space–Album Review

•

February 13, 2026

Loading...

1 thought on “Interview: John Densmore”

Some very interesting and true insight in what it takes to be a true musician playing Drums in a Band. I can relate to John’s sense of time or poly rythims because I used to play saxaphone when I was in High School. Some how though John deserved a little more grattitude in this interview,, I can tell he’s an intelligent and Cool Dude … Right On !