Interview: Steve Kilbey of The Church

Interview: Steve Kilbey of The Church

Jason LeValley of Psychedelic Scene:

All right, great. So thank you so much for joining me.

Steve Kilbey of The Church:

Hi. James?

LeValley:

Yeah, it’s actually Jason.

Kilbey:

Jason. Sorry. Jesus Christ.

LeValley:

It’s all good. James is my dad’s name.

Kilbey:

Jason LeValley?

LeValley:

That’s right.

Kilbey:

It’s a hell of a name.

LeValley:

Well, thank you. I appreciate that.

Kilbey:

I would have been ripe much further up the rank if I’d been Steve LeValley. It’s got some serious gravitas.

LeValley:

Oh, thank you. And thanks for doing this interview. I really appreciate it.

Kilbey:

No worries.

LeValley:

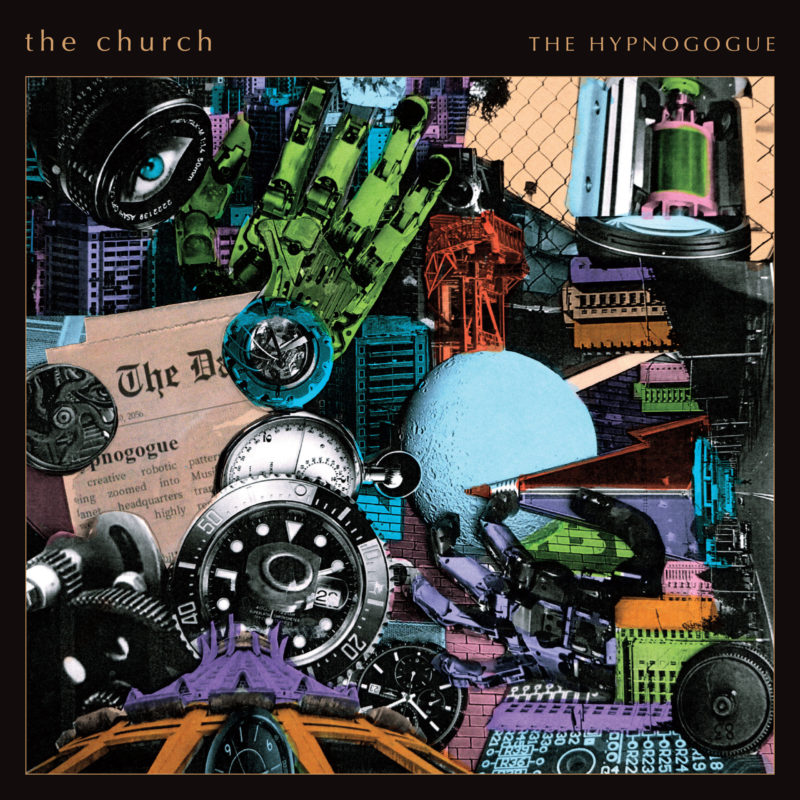

So the new album which just came out today is called The Hypnogogue, which is The Church’s first-ever concept album.

Kilbey:

Yeah.

As we started to record the album, things started to happen and the idea gradually sort of took root in my mind that it should be a concept album, it should be sort of sci-fi feeling.

LeValley:

And it takes place in the year, I think, 2054.

Kilbey:

Correct.

LeValley:

Where did the inspiration for this album come from?

Kilbey:

Well, it all happened gradually. It wasn’t like I said, “We’re going to make an album called The Hypnogogue set in 2054”. As we started to record the album, things started to happen and the idea gradually sort of took root in my mind that it should be a concept album, it should be sort of sci-fi feeling. It should be about the nature of creativity and songwriting, which is what we were doing. And then things would happen automatically. Lines in the songs would come to me out of the blue. And then it all happened so gradually, the more I thought about it, the more it took shape, and it kept on taking shape over the four year period. And we talked about it, and one day Tim said, he said, “we’re all just workers in The Hypnagogue, aren’t we?” I said, “yeah”. And then I almost had the idea there were human beings in there as well, helping translate. So someone goes in there and says, “I want to have the hypnogogic process”. And then there are actually musicians who are sort of chained to their instruments in little chambers. And when the person undergoes the process, there’s actually real players in there playing.

Kilbey:

And just little ideas and small inklings would come to me bit by bit, the whole thing fell into place, into the kind of the very loose concept it is now. So it didn’t come from the beginning. When I said, “Hypnagogue 2054”, it was like as we were making the album, as we were writing the songs, as the lyrics were coming out and the music progressed, I thought to myself, ‘Wow! we’re making a concept album’.

LeValley:

Cool. Well, I’ve watched the video, the two videos, “The Hypnogogue” and “No Other You”, and they’re both very cinematic and they seem to be related.

Kilbey: Totally.

And I was wondering if there’s going to be a video for every song on the album, and if it tells a complete story.

Kilbey:

Wish there was, I would love that. If someone said, “Hey, we want to make a video for every song”, I would love that. And I would love that guy to do it. He understands. He’s off and running with what it is. Now. I think that would be fantastic. Probably won’t happen, but I would jump at the opportunity.

Hugh Stewart

LeValley:

Yeah. Well, you mentioned in a recent interview that this album, The Hypnogogue, is likely to be the last Church album. What makes you say that?

Kilbey:

Well, when you get to my age, which is 68, everything could be the last. It could be the last. It’s like when my dad died when he was 51. Suddenly I’ve grown up in the shadow of that, knowing that that’s possible. And I feel like it’s not like when you’re 25 and you think, ‘Oh, I’ve got hundreds more records to make and hundreds more shows to play. I feel when you get to this age, everything could be the last one. I think I might have been feeling very pessimistic, thinking this would be a good one to go out on. I still think that this would be a good record. If we don’t make another record, this would be a good record to end on. However, last night we had a fantastic gig in Sydney, and when we finished, I just walked off and started talking to the others and said, this can’t be the end. We’ve got to do one more record. Surely there’s at least one more in us. And they were like, “Yeah, I don’t know”. But when you get to this advanced stage, anything could be the final anything. There’s no guarantees anymore.

LeValley:

There are plenty of musicians that are continuing much later in life than you are. McCartney, for instance.

Kilbey:

Who? McCartney?

LeValley:

McCartney.

Kilbey:

He probably has to be more guarded about what he says than me. And he would never mention his mortality. I’m sure that he’s not allowed to say that, but he must be. At 80 years old, you must be thinking, this could be my last show. This could be my last record. This could be my last fucking eggs on toast. It’s just the way it is. Look, I hope I go and have as long a life as he is as he has. Anyway, it’s just a bit of pessimism, I guess, or sort of a way of going– what was it that Richard Nixon always said? He used to say, “You won’t have Richard Nixon to kick around anymore”. I guess that’s my way of saying to the music business, you won’t have Steve Kilbey to kick around anymore. When I die, you’ll miss me and you wish you liked me more when I was around. I guess that’s just a way of saying that I shouldn’t really say it. I’ll tell you what, it really upsets my children when they read that. My five daughters, they read that and they go, “no, dad, no”.

LeValley:

Well, I read that a fan asked a Chat GPT to write a song in your style and that you didn’t think the song was very good. Have you ever tried using Chat GPT yourself?

Kilbey:

Why would I?

LeValley:

I don’t know.

Kilbey:

I’ve already got that. I’ve already got my own version of that in my head. I can write a song in my style whenever I like. I can write songs in other people’s styles, too. Much better than that. If you asked me to write a song in almost anybody I’ve heard of style, I could probably do that. So I don’t need that device to do it.

I don’t think you could find many people in this world who understand songwriting and lyrics and production techniques the way I do.

LeValley:

Well, this question was given to me by a friend who’s a huge fan of yours. And I’m not sure that he meant, could you write a song in your own style? I think he just meant, have you ever messed around with Chat GPT?

Kilbey:

I haven’t.

LeValley:

Okay.

Kilbey:

And in a way, that’s what the hypnogogue is. In a way, the hypnagogue is like another version of that. The hypnogogue is a singer who can no longer write– a pop star who’s dried up, as someone wrote in their review. The pop singer is having a moribund career and he goes and undergoes the process. That’s kind of what it is. And the machine delves right into your mind and pulls the song straight back out again. So I’ve always had that going on. And looking at the results of what I’ve seen, I saw the one someone did for Nick Cave and I saw the one they did for me. I was kind of unimpressed. And I was also really happy because no matter what a program can do, maybe it can make that grotesque art that it’s making. Maybe it can do this and do that. I guarantee you, machines are never going to write poetry. They’re never going to write lyrics, they never can, and even other human beings. So you can get the most brilliant minds on the planet and, say, write a song like Paul McCartney would have in his heyday, or write a song like David Bowie.

Kilbey:

And even we can’t pull it off because there’s some quirky individualism that no one can imitate or simulate. So I was really happy to see that that machine couldn’t write a song like me because there’s still some random process that nobody can understand that creates. And when you hear a really great lyric, it’s so often hard to understand what it is that’s great about it, that there are lyrics that fascinate me, and I go and look at them and go, what is it that I find so fascinating? And even when you’re really intensely looking at it, it’s hard to understand what it is. It’s sometimes a great lyric combined with the way the singer sings. It defies any analysis. And I consider myself like a PhD level. I don’t think you could find many people in this world who understand songwriting and lyrics and production techniques the way I do. With all my experience and my age and all the records I’ve listened to and my obsession on it, I understand what makes the things that I like. I don’t understand all music, but the music that I like, the kind of rock and roll–We’re talking about psychedelic rock and roll: The Beatles, Bowie, Dylan, Mark Bolan, the Rolling Stones. Talking about those people. I think I really understand it and yet it’s still why you get that thrill that maybe one syllable the other way or one inflection is off. It wouldn’t be so perfect. It remains elusive and I don’t think a program will ever be able to write a decent song. I just don’t think–I can’t see it. There’s something that will always elude the program. The programs might write some songs that are hits on the radio and kids are singing them and stuff but they’ll never write anything like “Strawberry Fields Forever” that will fascinate and obsess people for their whole lives. I don’t think the machine has it in it to do that. There’s still something special about the human mind and like a genius like John Lennon or Bob Dylan that they can create these lyrics with just one flick of a syllable. It just sends you off for the rest of your life. Yeah, anyway, I belabored that point. You understand what I’m saying?

LeValley:

I do, yes. You mentioned these artists and you referred to them as psychedelic. I’m wondering if…The Church is often regarded as a psychedelic band and I’m wondering what’s your take on that? Do you consider The Church…?

Kilbey:

For want of a better word we’re not really a psychedelic… It’s a bit like someone saying I’m eating European food or I’m reading a sci-fi novel or I’m wearing hipster clothes. It really depends a lot on what you mean by this word “psychedelic”. Now there are bands who are psychedelic like, for example, back in the very day when psychedelic rock was invented– The Beatles invent psychedelia, they invent this form, suddenly there were bands springing up, they’re paying like The Strawberry Wristwatch or whatever the fuck. There are bands that spring up that are paying lip service to the idea. So they’ve got the clothes, they’ve got a Nehru jacket and a Vox Teardrop guitar and they’ve got the haircut. But still, at the very core of what they’re doing, there’s nothing psychedelic. There’s no sort of transformative surrealistic process going on. So you can say I’m in a psychedelic band just by your clothes and your attitude and your demeanor, but really, there’s nothing psychedelic really going on in your music. There’s no mind-bending stuff happening. So it really depends. When people say a psychedelic band, I have gravitated to that word and embraced that word only because really the category for The Church never has really been invented.

Kilbey:

40 years, 30 years ago they said we were “mope rock”. Guys in America said The Church were mope rock. Mope rock. M-O-P-E. I guess that means that was a primitive word for emo or something. But I don’t know. So I’ve just always thought psychedelic is not a bad term to describe what we do. Although anybody could immediately demolish that categorization by going, “You’re not really psychedelic. You don’t do this or you don’t do that”. I don’t even know who is psychedelic anymore. And then to confer the confusing these days there’s this thing called “psych rock”, which comes obviously kind of comes from the word “psychedelic”. But from what I can gather, we are definitely not psych rock, which is sort of like a bad acid trip. It’s not sort of going for the beauty and the dreaminess. It’s like if an acid trip was more heading towards the speed, the amphetamine side. That’s kind of what psych rock does. Whereas in my idea, my psychedelia, I don’t want it to only be that. I want to have that as well, but I want to have the kind of the dreaminess in the hypnogogic state, which The Hypnogogue is named after–the idea where ideas are sort of fluid and loose in your mind. The thoughts are turning into dreams and the dreams are turning into thoughts. That’s the kind of thing I’m trying to approach. Not wearing a certain sort of shirt. But The Beatles did it and then they got out. The Beatles made like ten really psychedelic songs and then they stopped doing it.

LeValley:

That’s right. And that was just when the whole genre was just getting going, like right at the end of when The Beatles stopped.

Kilbey:

Yeah, that’s right. They abandoned it and left it to all those other bands: the Move and whoever the fuck it was who all jumped on that thing. Some of it became…I don’t really like a lot of it, to tell you the truth. And it’s amusing to see, actually you listen to Rolling Stones and see how they kind of got it wrong as well on Their Satanic Majesty’s Request that they thought, “Oh, we can do this”. But they never approached “Strawberry Fields Forever” or “I Am the Walrus”, which I think to me they remain the two absolute crowning moments of psychedelic rock where… The tragedy is they kind of did it and did the very best thing anyone could do and then stopped and nobody’s really been able to equal that since. Nonetheless, I go on trying to sort of write my own Strawberry Fields Forever, which, of course, is impossible, but nonetheless, I feel like it’s a worthy aim to have.

Marijuana doesn’t write the songs, but it puts me in a state where I can perceive things that I like really quickly.

LeValley:

Sure. Is your music directly influenced by psychedelics?

Kilbey:

No.

LeValley:

Okay.

Kilbey:

No, not really. I would say if my music is influenced by any drug, it’s marijuana. Psychedelics are very hard to harness and very hard to write. To take acid or mushrooms and write a song is very hard for me. I find it much easier to smoke marijuana. It’s much more controllable and doesn’t do any weird things to me that are unpleasant that I’ve got to cope with. I think sort of at the bottom of my creativity has always been marijuana. Marijuana doesn’t write the songs, but it puts me in a state where I can perceive things that I like really quickly. So when my band’s jamming, if I’ve smoked a joint, I can hear things that I like very quickly. Like a phrase will go past, and I’ll stop the band and go, “That phrase there, that’s the one I want!” Which, if I hadn’t been smoking, I might not have been able to spot. So it potentiates my creativity, but it isn’t my creativity. My stuff doesn’t come from drugs. It’s just that drugs make it easier to sort of get at it, I think.

LeValley:

Okay, all right, let’s see. Well, I wanted to ask you about…you’ve mentioned a couple of times that you believe you have Asperger’s syndrome, and I was wondering what makes you say that?

Kilbey:

You know what? There’s a lot of people running around saying that, and there’s a lot of people saying it to other people as well. My brother’s eldest son was diagnosed with it when he was a child. He’s grown up now, and as he was growing up and as my brother was dealing with it, my brother would bring me up and go, “It’s you all over. It’s you all over again”. And he’s going, “This is what you had. This is why you were such a handful and why you were such a sort of…” because people didn’t understand. But when I look back at my classroom of kids back in 1962, which one of them didn’t have something that these days someone could categorize in some psychological manner and go, “That kid’s got AAD. That kid’s got ADH. This one’s got Narcissistic Personality Disorder, this one’s autistic, this one’s got Asperger’s”. I mean, everybody has the touch of something. I guess I’m Asperger’s in the way that I can focus endlessly on the things that I love, and I can’t focus at all on the things I’m not interested in. Which is why all my school reports said he could do much better.

Kilbey:

Because they looked at me and went, “Wow, this kid can eat up Greek mythology but put arithmetic in front of him and he can’t do anything”. And it’s sort of an inability to be able to use my mind. I’d say to myself, ‘hey, come on, we’ve got to do this mathematical thing’. And I’d look at all those numbers and stuff and go, ‘nah’. And I go, Come on, get onto it. And I go ‘nah’. And I guess other people who don’t have whatever this Asperger’s thing is, I guess they can do that. I said to a friend of mine just recently, I said, “You did so well at school. And she said, “I didn’t want to I didn’t like maths or science”. She said, “I just had to work hard and apply myself”. And I said, “that’s the thing I couldn’t do if I didn’t like it”. I just couldn’t take it in. I also have something I think called semantic hyper priming, which is like words aren’t just words to me. And it’s like a test they use to determine madness. When they say, “I’m going to say a word, you say the first word you think of”.

Kilbey:

And when the psychiatrist says, “dog”, you’re supposed to say “bark” or “walk” or “bone” or “cat”. Your mind is supposed to be a normal person. Your mind is supposed to look at words and go like this. But when someone says “dog” to me, I have millions of other associations that, if I was a madman, wouldn’t be right. However, as I’m a poet and a lyricist, it’s good for me to be able to do that. So words have all kinds of different associations to someone with semantic hyper priming than they do to a normal person who just hears the word dog and thinks, “walk”, “cat”, “bone”. But to me, when the guy says “dog”, I might say something else that wouldn’t make any sense, and he could go, “This guy’s a loony, you see?” But as a lyricist, it’s all right to be that, because I’m using my dysfunctionality to create stuff.

LeValley:

So it helps your art.

Kilbey:

Yes, that’s right.

LeValley:

I understand that you also painted.

Kilbey:

I’m not a great painter. I started too late. I don’t have any technique. I struggle with things. I struggle with things. If I really knew what I was doing, I wouldn’t have so much of a struggle. I’m sure I’m not a great painter, and I don’t pretend to be. I don’t think I ever will be. And it’s very much if you like my music, you might like my paintings. But I’m not sort of pushing myself forward as a great painter by any means at all.

LeValley:

Do you have your stuff posted online so fans can check it out if they’re interested?

Kilbey:

Yes. You can go to thetimebeing.com, and there’s all my archive art is there, or some of it.

LeValley:

Okay.

Kilbey:

Or skram on Instagram. You can go to Skram S-K-R-A-M. And some of my paintings are there, and I do commissions and stuff. But there’s a little example of my painting on this album cover of the lady who invents The Hypnogogue. I’ve done a painting of her looking at herself in a mirror, and there’s the mechanical nature and the vegetable nature of the machine. And she’s sort of sitting there in both worlds manipulating the hypnogogue. But I’m no polymath. I’m no Leonardo da Vinci. My main thing is writing lyrics and playing bass guitar and all the rest of it is neither here nor there.

LeValley:

Okay. You mentioned that you have daughters and you have five daughters.

Kilbey:

Five daughters, yes.

LeValley:

And no sons.

Kilbey:

No sons.

LeValley:

And you have two sets of twin daughters.

Kilbey:

Yeah.

LeValley:

Wow. What are the chances of that?

Kilbey:

Literally 100,000 to one in having two sets of twins, different mothers. And the first set were identical twins. The second set of twins were non-identical twins. Yeah.

Alarmy

LeValley:

And the first set of twins has a band that is actually pretty successful. I’d never heard of them, but I looked them up on Spotify and saw that they have a number of songs that have over a million streams. I was surprised at that. Say Lou Lou. Did you have a role in their development?

Kilbey:

No, purely no. They never asked me nor sought…They didn’t seek my advice. I didn’t give it to them. They arrived at this on their own. And I used to say to them, “Don’t you want to be musicians?” “No. That would make you happy, wouldn’t it?” It’s like “Yeah, it would”. “No, well, we don’t want to make you happy. We got to rebel”. We’ve got to rebel against whatever our parents are just like me. My dad said, “you could come and work in my business”, and I’m like, “I don’t want to do that”. So I guess they rebelled against it until their genetics got the better of them. And there’s a lot of music sort of running through the family. And their mother was sort of a songwriter, too. And so I guess in the end the genetics went out and they went, “Hey, this music thing isn’t that bad, actually”. And I’m really proud of them. I think they write really good lyrics, especially as English isn’t really their first language. It kind of is, but they’re really more fluent in Swedish than they are in English. And they write really good lyrics. It’s interesting to me to see. I think this…it sort of runs in their genes.

Kilbey:

Some people, their dad was maybe a carpenter, and the first time they pick up a piece of wood, they have this affinity with it. And my affinity is with words and writing lyrics. And it was very satisfying to see that they had the same kind of affinity with words and they could turn a phrase. It’s a very fine science, writing lyrics. As I was saying before, one misstep, and it’s not good. And when I see the lyrics they write, I’m really proud of them.

LeValley:

That’s great.

Kilbey:

My friend. I’m sorry, we have two minutes.

LeValley:

Oh, two minutes. Okay.

Kilbey:

I’m sorry, Jason.

LeValley:

We can wrap this up.

Kilbey:

Okay.

LeValley:

Well, thank you. I wanted to mention to you that we have the same birthday: September 13.

Kilbey:

No way.

LeValley:

Yeah.

Kilbey:

What year?

LeValley:

‘65.

Kilbey:

You’re a lot younger than me. How I would love to have been born in 1965.

LeValley:

Seriously?

Kilbey:

Well, I wouldn’t be fucking 68 now, would I?

LeValley:

Well, no, no.

Kilbey:

I’d be 57, right?

LeValley:

That’s right, yeah.

Kilbey:

And 57 seems like spring chicken to me at this advanced stage. Let me give you a word of warning, okay? I thought my 50s were a joke. I was like, i”f this is getting old, bring it on”. I’m 50. I was killing it. When I hit my 60s, things really slowed down.

LeValley:

Okay.

Kilbey:

Enjoy your relative youth while you still can, Jason.

LeValley:

I will. I’ll live every day like it’s the last day on earth. All right, well, thank you.

Kilbey:

Thank you, mate.

LeValley:

The album The Hypnogue is out now, and I’ve listened to it a number of times, and I think it’s great. I wish you a great tour of the US. And thanks again.

Kilbey:

Thank you, Jason.

The Hypnogogue by The Church–Album Review

Eros Zeta and the Perfumed Guitars by the Church–Album Review

T

Scott Dudeleson/Getty Images

Gallery

Recent Articles

Can Molly Mend Your Marriage?

•

February 16, 2026

Immer Für Immer by Flying Moon in Space–Album Review

•

February 13, 2026

Loading...