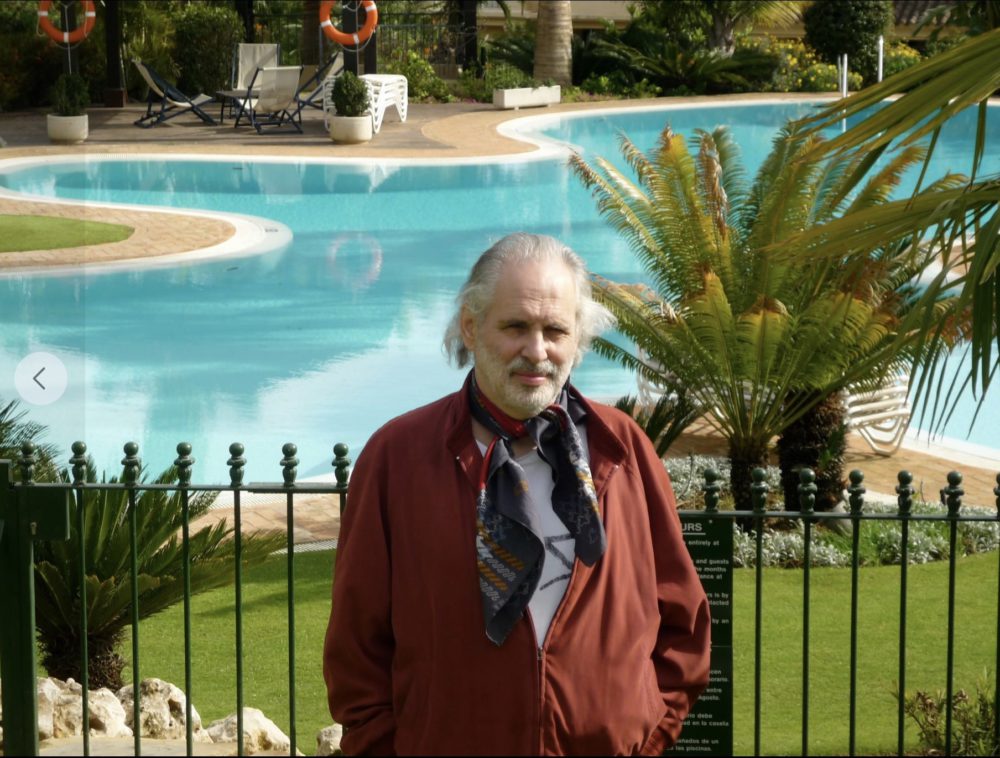

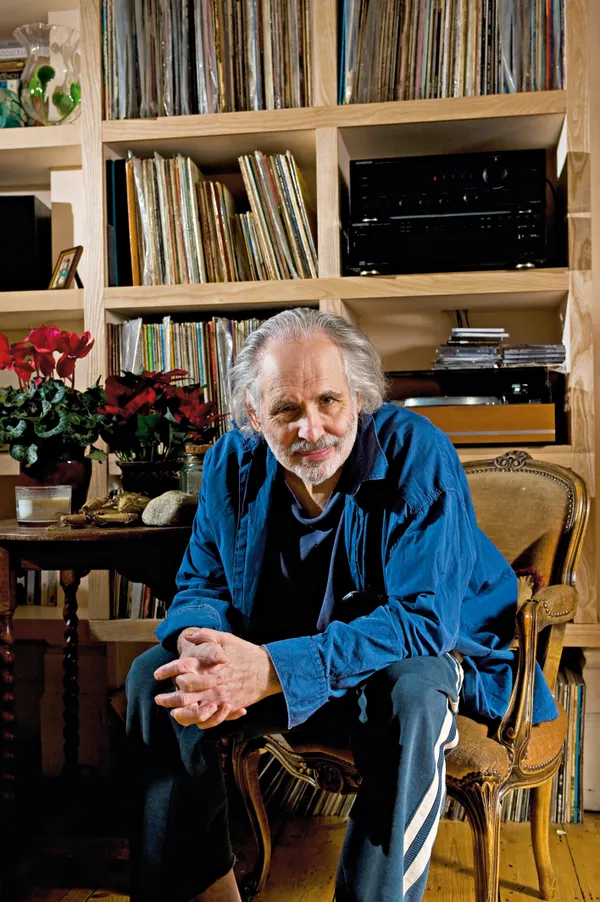

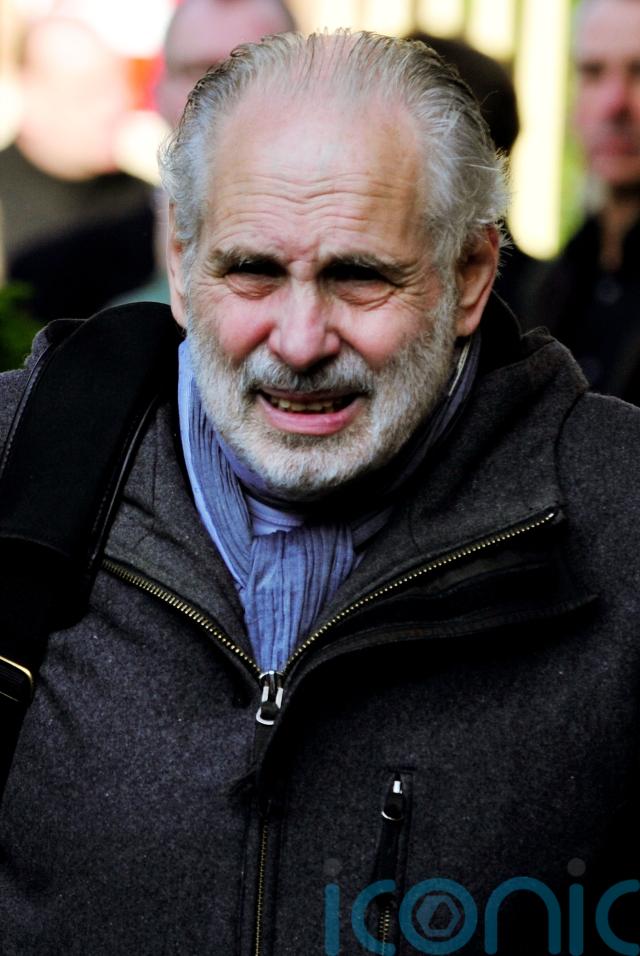

Interview with Cream Lyricist Pete Brown

Interview with Cream Lyricist Pete Brown

Bassam Habal of Psychedelic Scene:

Here we are talking to the legendary Pete Brown. Good to hear from you, Pete.

Pete Brown:

Yeah, thank you.

Habal:

Tell me about some of your early sort of leanings towards writing poetry and some of your early influences that got you wanting to write.

Brown:

Okay, well, I started writing because I had an imagination and the imagination was going crazy all over my schoolwork and so one of my teachers, two of them actually, suggested that I write stuff that was nothing to do with schoolwork and got off in that way and didn’t get in the way of schoolwork. So I started doing that, both in bits of terrible stories which I wrote at one point and mostly science fiction, and some poetry. The poetry sort of worked. I mean, the first of it was terrible but then I started looking around for kindred spirits, famous ones, you know, and I lit on Dylan Thomas and then I lit on Lorca. And then the beats came along, you know, and the beats were doing something very special, because they were sort of professional, you know, they weren’t, or most of them were not academic. Some of them were even working class, like Corso and people and they were also traveling and reaching audiences, which previously had not been reached before and that appealed to me. My first poetry was published, in America anyway, in the very important magazine, Evergreen Review. That was a big encouragement to me.

Habal:

How old were you then, Pete?

Brown:

17 or 18. I had previously sent lots of poetry to British magazines, and got it rejected, but America has always saved my bacon and they rescued me then, and funny enough, today, they’re rescuing me again. Well, I’ll tell you about that later. And so I met this other guy, who was similarly influenced and he had a magazine of his own, but he was wanting to do live shows, a guy called Mike Horovitz. He’s dead, unfortunately, and he had a mixed group of performers. He had some actors, he had musicians and poets and stuff and I joined that group. And we were sort of on the road and we gradually built up a following and built up a circuit of places where you could go and read your own poetry to mostly younger people, obviously. And then, because the movement was happening, I mean, it was a raggedy movement. There was no one particular

I had previously sent lots of poetry to British magazines, and got it rejected, but America has always saved my bacon

theme to it. It was just doing things live and being a poet. And when we attracted interest from America, and gradually built up to the big poetry reading at the Albert Hall in 1965, with Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti and all these people. Meanwhile, we had refined the group down to two poets and a jazz group featuring some of the best musicians in the country and that was working fairly regularly. We even had a residency at the famous Marquee Club in ’63. And then after the great big Albert Hall poetry reading, then we were earning a living almost and then the next year you know, I had always been a jazz and blues fan everything and was friendly with a lot of musicians, some of whom had worked in the poetry group including one guy called Dick Heckstall-Smith. And that’s how I met Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker because they worked with him sometimes.

Habal:

They were working with the Graham Bond Organisation or…

Brown:

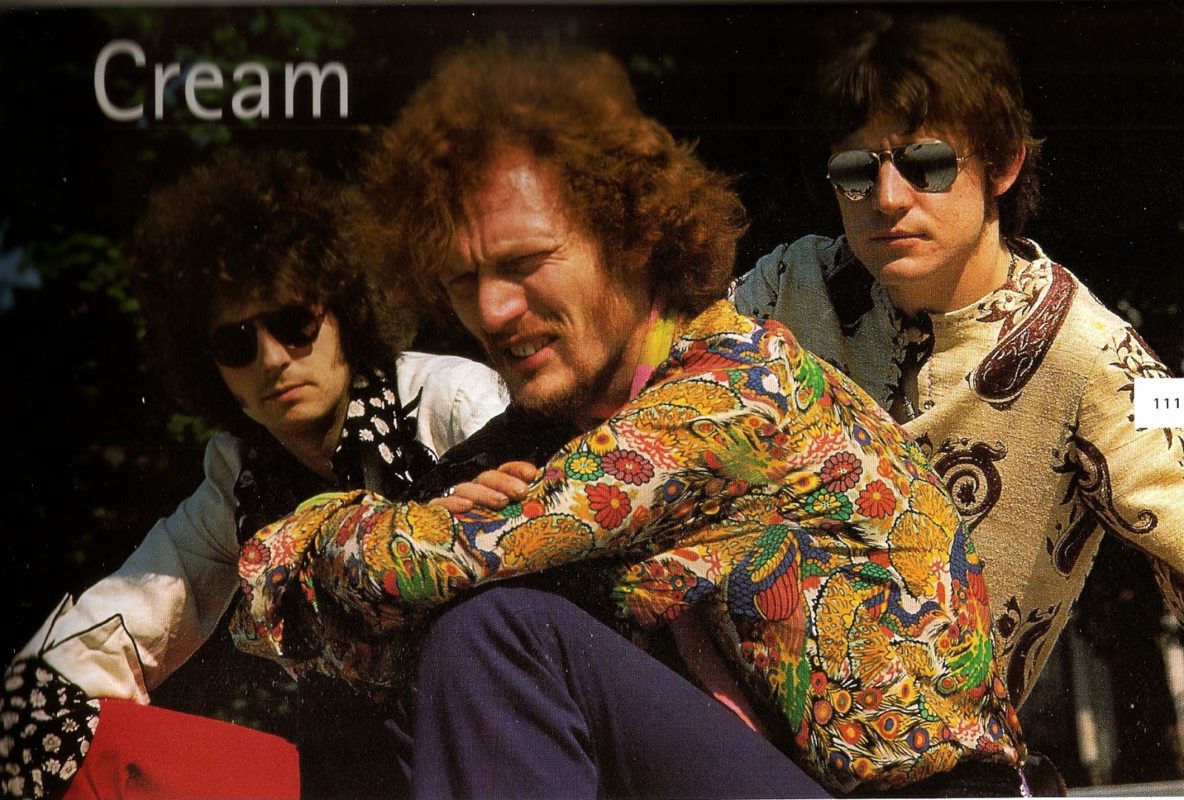

Well, yes, yeah. They started off working with Alexis Korner and then they graduated to the Graham Bond band and I loved the Graham Bond Band. Dick Heckstall-Smith and Graham both worked in the poetry group as well, so that became a little family if you like. And then the next year after the Albert Hall thing, then I got the phone call from Ginger saying, you know, “We’ve formed this band, and we’ve got a track here and we need some lyrics, you know,” so I went down to the studio lyrics for what became “Wrapping paper.” That was their first single.

Habal:

Now when you wrote “Wrapping paper” were you working with Ginger as a collaborator?

Brown:

They wanted to collaborate, generally. Eric wasn’t really writing hardly anything. Ginger was writing things that were pretty far out. But somehow there was, which was very powerful, this chemistry between Jack and myself, which was first successful when we got “I Feel Free” into the big jobs and everything, and everybody loved it. And that was really the beginning of a 48-year relationship. And then we had the hits, of course, “White Room” and “Sunshine of Your Love”, and so I was in the business and then eventually, after a couple of years, I formed my own band and started singing.

Habal:

Now I know that you worked a lot with Jack but also Jack, I guess, worked on his own for “N.S.U” which was strictly a Jack composition.

Brown:

Sure, he wrote his own stuff as well.

Habal:

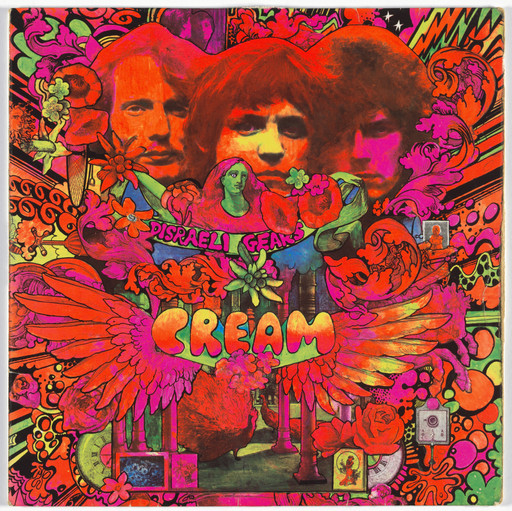

What can you tell me about “Tales of Brave Ulysses” which I thought was a Bruce-Brown composition but it turns out the lyrics were written by Martin Sharp? What can you tell me about Martin Sharp?

Brown:

Martin was an artist who did the Cream covers, you know, he did the “Disraeli Gears” and “Wheels of Fire” and he’s an artist but basically had some writing talents and he was a friend of Eric’s. They were living in the same place. At one point, I was living there too, only for a few weeks. And funnily enough, somebody’s writing a film right now about that time, in that particular place, the Peasantry which I have contributed to. He’s a friend of Eric’s. So, there will be a feature film about those early days and the bohemian life in London. But yeah, Martin was quite a talented guy. I think that was the only lyric he wrote. But he did the covers for the records. He was a talented artist.

Habal:

What can you tell me Mike Taylor (Mike wrote songs with Ginger like “Pressed Rat and Warthog)?

Brown:

Mike Taylor was a wonderful musician, very, very dedicated. He started off as a semi-pro but always with great bands like with people like Tony Reeves and Jon Heisman and he started off just playing Monk and Art Blakey compositions.

Habal:

Was he a piano player?

Brown:

Yeah. And he started off as a commercial artist but then he gradually became more and more dedicated and just did music and made two albums. Jack is on the second one playing standup bass. Heisman is on both. And he was a great musician and some of the compositions that he made both for his own band, which was just a quartet and also for the New Jazz Orchestra, which was a big band, are absolutely astounding. They stand up incredibly well. Unfortunately, he took too much acid. His brain went and he walked into the sea and drowned himself at one point. There is a book about him.

Habal:

Were those albums under his own name?

Brown:

Yeah. I believe they’re being reissued. They cost an awful lot of money to find the original vinyl but I think they are about to be reissued.

The blues is very largely about the war between the sexes from both sides.

Habal:

That’s great. What does the tune SWLABR from Cream’s 2nd LP mean? I’ve heard rumors that it stands for Southwest Los Angeles bearded rainbow or she walks like a bearded rainbow.

Brown:

No, she was like a bearded rainbow. Thing about, and I have to say this, because in today’s age, you know, things have changed a lot. And I mean, the blues, as you know, is very largely about the war between the sexes from both sides, from the female side and the male side. Of course, if you really listen to some of the great early blues material, then it’s women being very, very hard on men as well.

“Hound Dog” is a great example.

All kind of stuff like that, and Hambone blues, you know, tons of it. And so it was a war, but artistically, it was almost equal in some ways because there were a lot of great female blues singers and R&B singers that were very successful and very prominent. But, in the male blues, of course, there was always a touch of misogyny and in some of those early songs, I’m afraid I did inherit it a little bit. So, unconsciously, of course, because I love women and I’ve always done so. I’m actually somebody that does really love women. And so, I was just doing some of the things that I wrote unconsciously because I was still very, very young and not 100% knowing what I was doing and being focused. “She was like a bearded rainbow” is about a guy who gets dumped and goes around defacing pictures of his girlfriend. There’s a kind of comparison with the famous thing about people trying to draw mustaches on the Mona Lisa. It was kind of influenced by that.

Habal:

What can you tell me about writing the song “White Room”? There seems to be a contrast between the yellow and gold to contrast with the black.

Brown:

Yes, well “White Room” is a very strange thing. The reason why it’s been so successful, I think, is because it’s like a movie. It jumps around it. The cuts are very movie-like. I lived in the cinema and I used to go four times, five times a week. And so my head has always been full of cinematic images. Even in that first song “Wrapping Paper”, there are bits of John Pauls, and there are bits of Orson Welles’ “Touch of Evil” and all sorts of things. “White Room” was also very edited, because it started life as an eight-page poem.

Habal:

Was that called “Cinderella’s Last Goodbye”?

Will Ireland

Brown:

No, no, that was another title for the same music, and I did write a lyric with that in mind, but it didn’t work. It was actually “Cinderella’s Last Midnight”, I think it was. It was a poem, and because Cream was on the road all the time, there was never any time to write, hardly any. And so that meant that all the ideas were considered, even just the germs of ideas were considered, some of which worked. And when we were looking for a lyric for the music, which was already written, and “Cinderella’s Last Midnight” didn’t work out. It failed, so I then, perhaps in desperation, or with certainly the clock ticking anyway, came up with this idea, the “White Room” idea and it was eight pages long. Luckily, I had been to journalism school for a short period and had learned to précis things, which is a technique whereby you reduce things to their essentials. And so, I was quite good at that, because I thought it came in handy and so I reduced it to one page from eight and it worked. Hey, presto.

Habal:

It seems to have stood the test of time.

Brown:

It really did.

Habal:

Now in the line, “Where the shadows run from themselves,” would that be kind of the ultimate encapsulation of a place of fear?

Brown:

I guess. I mean, it’s a thing that you can think of it as a set of images. And they’re in a kind of a sequence, a logical sequence that may have not seemed like it to start with. It’s not very calculating, but the intuitive thing about it was that these things would work together, and they flowed. And they flowed when they were written. And so they have their own logic. And, I mean, it was one of the two Cream songs that were written about my own experience. And it was when I was kind of going through a woodshed period in re-evaluating what I was doing and who I was and everything. There was an actual white room. I had been, for a long time without money, well hardly any money, and was just starting to write songs. I’d been staying with various friends on living room floors and whatever. And then suddenly, I just began to have enough money. And so, I moved some of the bits that I’d acquired over the years into this pristine white room and started a new page as it were and all these images just flowed into it, you know? It was like a kind of woodshed period for me and then also, it was the place where I kind of gave up drugs and alcohol as well, which is also slightly reflected in that,

Habal:

How much input did Jack Bruce give you in terms of a lyric alteration or idea, generally speaking?

I always felt that, especially with Jack, I was almost like translating his music into words.

Brown:

Yeah. We wrote in every way imaginable: sometimes the lyrics came first, but mostly the music came first. I mean, the other thing about “White Room”, of course, is that the music was there and it suggested all those things to me anyway. I always felt that, especially with Jack, I was almost like translating his music into words. In the best instances, I think that’s what really happened. I got really inside him and even though that was about me, he identified with it, and with a lot of the others, and then again, sometimes, especially later on when I was working with him on the solo albums, then very often he would, I would sort of say to him, “Okay, here’s the music. I feel something from it, but tell me what it’s about if you know what it’s about.” Sometimes I would get it anyway without having to have any explanations but other times he had quite specific ideas about what he wanted songs to be about, which was fine because that helped me anyway.

Habal:

What was the inspiration behind the song “Never Tell Your Mother She’s Out of Tune” from Jack Bruce’s first solo LP Songs for a Tailor?

Brown:

That was Chris Spedding(the guitarist on the album). Apart from the fact that it’s a semi-nonsense song full of images, which I just liked, and Jack liked singing. But that one was, Chris Spedding’s mother was a musician and she was in a choir and Spedding went to one of her gigs. And she said to him, “What was it like?”, and he said, “It was out of tune.” He told me this story because he was in my band before he was in Jack’s band. And so, I thought that was a great title. You know, I loved it.

Habal:

That’s great. What would you say the differences are between lyrics and poetry?

Brown:

Yeah, I mean, some of the lyrics are close to poetry and others are nothing to do with it at all, a completely different idiom because my early experience was poetry and I still write it sometimes too. I’m not generally speaking, these days, especially. I’m generally speaking, not trying to make it too poetic. I’m trying to make it so everybody understands it. But on the other hand, because I’m using very strong imagery a lot of the time then, some of it gets toward poetry in the same way that poetry imagery works. Mostly, especially these days, I’m trying to write more simply and have a more emotional impact. But it still means that I do have the poetry influences. It’s still there. I still write poetry sometimes as well and it is quite different but they do overlap a little bit.

Habal:

Yeah, I’ve always felt that certain things work in terms of the meter of a vocal and whatnot and then certain things read great as a poem but fall horribly flat as a song due to possibly the meter having the lyrics or other reasons.

Brown:

That’s very interesting you should say that because, obviously, if I was writing with Jack, for instance, then it’s quite clear that, apart from the fact that I felt while I was translating the thing into words, some of which kind of almost wrote themselves, but then again, they’re very specific feelings, some created by melody and rhythm that steered these songs in certain ways. Whereas apart from some, I mean, like “White Room” doesn’t have any rhymes in it, but a lot of them do and the ones with rhymes, of course, are more and more song-like. Of course, it goes both ways. I mean, I write a lot of poetry where there aren’t any rhymes and it’s just down to imagery and what poetry is saying. But then again, I’ve got a very strong influence, for instance, from somebody like Edward Lear who is one of my favorite poets, you know, and all of that is rhyming and rhythmic. And so that’s, in some ways quite closer to song, but in fact, it’s poetry because it’s about certain things that don’t really necessarily go into songs. Subject matter as well, some songs are really suited to certain subject matter. I mean, for instance, the most popular song I wrote with Jack outside of Cream is “Theme for an Imaginary Western”. And the thing about that is, you know, the initial impetus came from the fact that he had the music and played it to me, and I said, “Okay, well, that sounds like Western music”. I love Westerns, I collect them, you know, and I’m quite an expert in knowledge about Westerns. And I felt that it wasn’t about the West, but there was a feeling of that epic sort of feeling, you know, and the traveling and the pioneering and then I thought also to marry it to an idea about the Graham Bond Organisation who were this kind of weird mixture of outlaws and pioneers. And so I thought, “Okay, well, that’s what it’s really about”, but it’s got the feeling of a Western’s ethic but same time it’s about these musicians of whom Jack was one, of course, that created that particular thing, and the way they lived, and the kind of way they worked; mythologized, you know, all of it, but nevertheless, completely about that, you know, and that’s how that song evolved. I still sing it a lot. You know, people love it, you know?

Habal:

What did you think of the Mountain version?

Brown:

It may have even come out before Jack’s, but it was originally written for Cream. You probably know the story that their manager, we did a lot of demos of various songs, and the manager deliberately lost them because he thought they weren’t commercial. And also, there was some kind of collaboration as well with Ahmet Ertegun, who’s running Atlantic and Ertegun didn’t like some of the songs as well, because he wanted a blues band, you know, with Eric leading it and not realizing the value of Jack as a singer or as a composer. But then again, he had to make a

He (Ertegun) had to make a big about-face because he called “Sunshine of Your Love” psychedelic rubbish, and it became the best-selling single that Atlantic ever had.

big about-face because he called “Sunshine of Your Love” psychedelic rubbish, and it became the best-selling single that Atlantic ever had. It just shows you those people misjudge things all the time. Not all the time but I mean, if Jack and the boys hadn’t really pushed him to sort of put the thing out, Christ knows what would have happened. But there you go, they did it, you know?

Habal:

Wow. It’s definitely stood the test of time. I teach kids and I’ve seen kids do it and it’s amazing. Was there a recording of Cream actually doing “Theme for an Imaginary Western” or like you said, it was one that got destroyed and never saw the light of day and was not in a vault anywhere to be found?

Brown:

When they did the big box set of Cream, then some of those demos resurfaced such as “Weird of Hermiston”. Unfortunately, the demo of “Theme for an Imaginary Western” didn’t surface so it may have been destroyed or lost.

Habal:

Interesting. Tell me about some other collaborations with people that you worked with that people might not know about.

Brown:

Well, quite honestly, when I worked with Jack for all that time, and then I was obviously working with my own bands and stuff like that, for a long time, that was enough. I wrote one song with Jeff Beck and Tim Bogert and that finally got onto a compilation, but it wasn’t issued at the time.

Habal:

What was the name of that?

Brown:

I can’t remember it but it is there somewhere and that same band recorded one of my songs that I wrote with Jim Mullen called “Living Life Backwards”. But I wasn’t running around trying to get work as a songwriter, which I do now. I do that a lot now. In very recent years, I did the last Procul Harum album, most of it. I’ve been working with Joe Bonamassa and had one very successful record with three songs that I wrote on that. I worked with young acts as well. There’s this guy called Krissy Matthews, who I think is probably one of the most creative and interesting British blues-rock kind of guitar players. I’ve done nearly four albums with him. I just do it because I like it. I’m working also with a guy called Solomon from New York, a young black guy who is a current blues-rock kind of guy. I’ve just written some songs for him for his new record. I will work with people. I’m trying to make a living. I do work with people now whose musicianship I admire, who I think have got something to say, and who are interesting. So I will take things on, as long as I get on with them okay and as long as I really like what they’re doing musically, but my main project this year, and early next year, is doing my own record again. I’ve been working on that and we’ve just been offered a deal. I’m aiming to get that out probably in March, or April of next year.

Habal:

Any thoughts about taking it on the road and, specifically, coming to America?

Brown:

Yes. I mean, the point is that I’m 81 and I’m in good shape in many ways. I do a hell of a lot of exercise. I haven’t had a drink or a drug since 1967. I don’t eat any meat. I don’t eat any dairy. You know, I look after myself. But I’ve had a few brushes with cancer, not spreading-type cancer but localized. In fact, I have to have an operation next week but it’s a very small thing and am I I’m assured by my very competent doctors that it’s not at all life-threatening or anything like that and that I can continue to be myself for quite a long time from now, so I’m hoping that’s true. Since COVID started to fade out a bit, I’ve been doing a few gigs here and there and it looks like from November onwards, I’ll be doing a few more. And then this record, if it all works out, is for an American company and so they will probably want me to do something. I also have this Detroit connection. I have kind of a thing going on in Detroit. I did a poetry festival there a few years back and have a lot of friends, and they want me to come back sometime next year and do some stuff, do a few poetry dates, and get a new little book out. I had one book published by these guys in Detroit, which I’m very happy about. So, I’m doing that. I still like to do the poetry. It comes and goes in phases. I’m writing songs all the time and I’m writing some film scripts. I’ve got a little film company. And we’re trying to get a couple of those off the ground, but the poetry sometimes, it fades for a year or so and then things come back because there are certain things that can only be said in that particular way and then I drift into it again. I’ve been doing quite a lot lately, actually.

Habal:

Glad to hear you keep busy. Tell me some of the other lyricists you enjoy. Are you familiar with Robert Hunter, who worked with the Grateful Dead?

Brown:

Yeah, he was good. I mean my favorites are Big Joe Turner, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, I think was one of the great lyric writers, Mose Allison, very, very fond of him. I had a sort of friendship with him. He used to work over here a lot. You know, Randy Newman, always was a good one.

Habal:

Did you know Keith Reid (who was a lyricist with Procul Harum)?

Brown:

Yes, I like Keith Reid a lot. He’s somebody I’ve got a lot of respect for. Joni Mitchell, I like a great deal. Victoria Spivey, Do you know her?

Habal:

Yeah, sure.

Brown:

Victoria Spivey was active since the late 20s and she was one of the first black women to have her own record company after the Second World War. Gave Bob Dylan his first session free– playing harp on one of her tracks and she wrote very quirky lyrics which I really love. That’s all

That was the idea in “Politician” of the pinstriped politician or with his, with his Daimler or Bentley, and trying to seduce young mini-skirted women.

good stuff. I mean, I’ve got quite a broad sort of mind about things. I like a lot of blues. I like a lot of the blues Willie Dixon wrote and I like a lot of early stuff like Blind Blake and people like that who come up with some funny lyrics.

Habal:

“Hit me with a chair till my head had got sore, crying that’ll never happen no more”(a lyric from Blake’s song “That’ll Never Happen No More”).

Brown:

Yeah, a lot of stuff. I listen to a lot of jazz, a lot of blues, and soul. I’m quite broad-minded, really, in most ways. Poets, I mean, I love Kenneth Patchen and Robert Creeley. They were absolute favorites. I did some shows with Robert Creeley and he was fantastic. I mean, incredibly skillful. Patchen is somebody whose politics are very much mine. He’s like an old American socialist–a bit like Lawrence Ferlinghetti was. I kind of run along those kinds of lines. Really, those are where my sympathies lie. I like a bit of justice and equality.

Habal:

Sure. Was the song “Politican” written as just a general theme/feeling or did you see a guy on TV and it sort of inspired you to do so?

Brown:

No “Politician” really was very specific, well, specifically influenced by the Profumo case, you know, in the 60s. John Profumo was the Minister of Defense and he had a penchant for call girls, young ones. And the call girl that he was most into, was also the girlfriend of the Russian naval attaché’ in London, who was, in fact, a spy, of course, as everybody was in those days. And so, somehow, which was very difficult in those days, but somehow the story actually did manage to get out and it actually brought the government down. They had to resign, a whole lot of them because it was so untogether and that was really what inspired “Politician” and also the fact that the changing of England, of Britain, was like between these traditional things of people in pinstripes and bowler hats and things like that. And then the beginning of swinging London and miniskirts and people stopped ceasing to wear formal wear, and the sexual sort of semi-revolution as opposed to the establishment who, of course, always did what they wanted but then they kind of tried to infiltrate the young people’s world, and that was the idea in “Politician” of the pinstriped politician or with his, with his Daimler or Bentley, and trying to seduce young mini-skirted women. In recent performances when I’ve done it, I’ve included a verse about Trump as well, “I’ve got my toupee rolled down to my knees, begging and a prayin’, please, baby, please.” I managed to get a bit of him into it.

Habal:

That’s great. Before we wrap up here, Pete, tell me your favorite Ginger Baker story.

Brown:

Well, one of the best things that Ginger ever did was they did this TV program. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it called “Rock Family Trees”. It was a British series, and we’re all in it and, at one point, Ginger is being interviewed and he’s smoking a pipe. And, of course, Ginger, being a drummer, had the most incredible sense of timing. You can almost relate to it. I mean, he wasn’t a comedian, but he was very funny. You know what I mean? Mel Brooks, as you know, was a drummer.

Habal:

I did not know that.

Brown:

Oh, yeah. No, he was a professional drummer. He worked in the Borscht Belt and his timing is incredible as well. Peter Seller, of course, was also a drummer and his timing is amazing. But Ginger is doing this interview on the “Rock Family Trees” program and the interviewer says to him, What about (John) McLaughlin? And of course, McLaughlin was in the Graham Bond Organisation before (Dick) Heckstall-Smith joined. He replaced McLaughlin, and Ginger is smoking a pipe, right? He’s smoking his pipe and he says, “McLaughlin? He was a moaner.” And then

I’ve had a few brushes with cancer, not spreading-type cancer but localized. In fact, I have to have an operation next week but it’s a very small thing.

there’s a pause and then sucks on the pipe again and then he goes, “I told him to fuck off.” It’s the funniest thing. You have to see it to really appreciate it, but it was one of the funniest things I’ve seen in my life. You know, I always quote it ’cause I love it.

Brown:

An interesting thing happened. We did this long project called the Cream Acoustic Record, and that eventually will be released in America in, I think, maybe January or February. A lot of people are on it: Bobby Rush, Maggie Bell, and Ginger with the last sessions that Ginger ever did. He plays on four or five tracks. I’m singing on it. Joe Bonamassa is on it, Bernie Marsden, and loads of different people, are all doing acoustic versions of Cream songs or songs that were associated with Cream. And there’s a great thing where the producer, who is the same guy, a guy called Rob Cass that’s producing my record produced the last Jack Bruce record as well, which is a great record. Anyway, Rob’s producing and Ginger is playing then gets to the end of a take and Rob says, “Sorry to say, but can we have one more take please” Ginger was very ill at the time, and he says (imitates Ginger), “You trying to fucking kill me?” We made a film of the whole thing and that will come out as well and it’s incredible what he does. Ginger was a real comedian.

Habal:

To me, any interview I see with him is just the funniest, most priceless stuff. I remember talking to the guy that did the movie “Beware of Mr. Baker” and somebody asked him during the Q&A at a film showing, “Has Ginger seen your movie?” and he said, “Well, I asked Ginger if you wanted to see it and Ginger said, ‘Why would I want to? I fucking lived it.”

Brown:

You know, there is currently, it only just started an American writer, a guy called Mark Shapiro, and he is writing a book about me currently. I’m helping him with it.

Habal:

Great. Well, look, I look forward to that coming out.

Brown:

I did write an autobiography in 2010, and that’s long gone but didn’t do very well because the guy that signed me to the company then got head-hunted and lost interest in it. But if there’s a lot of interest next year, then I might try and rewrite it and get it going again. I don’t know. We’ll see. But meanwhile, this guy who’s writing this, I’m doing long interviews with him about it. It’s good, I’m enjoying it. He’s a nice guy. I have to say this: I’m very pleased, at the moment anyway, that there is so much interest in what I’m doing. I’m doing a lot of interviews with people and all sorts of stuff, which is great. I mean, I know that part of it is because everybody else has died and I’m one of the few survivors with a brain left. I can actually remember stuff and talk about things, which I’m quite happy to do. I mean, I don’t have any problem with it at all.

Habal:

Well, your work has stood the test of time. That’s for certain.

Brown:

Oh, yes. Well, that’s an interesting thing you see because, when you’re talking about the stuff that I grew up listening to, and Jack as well, we listened to the blues, and jazz and everything and, in Jack’s case, quite a lot of classical music, too, which I also listened to a bit of but we also listen to the standard repertoire, what they call the standard repertoire, which is the great standard: show tunes, and everything, things like “Body and Soul” and stuff like that and it rubbed off. These things may have been made for specific and temporal reasons but they survived because they were very, very well-made. In a way, that’s where we got that kind of inspiration to not just do tissues, to do stuff that somehow was built in that the stuff that we were doing was inspired by stuff that lasted. It wasn’t that conscious but, on the other hand, we weren’t thinking of it as pop frippery. It was more serious than that, so it turned out that a lot of it lasted, which is great. It’s really good. I’m happy about it. Well, it’s the reason I live in a house.

Habal:

Are you in London or outside of London?

Brown:

Well, I lived in London for a long, long, long time but nine years ago, we moved to the seaside in a place called Hastings in the southeast about 70 miles from London. We love it here. Can I just ask you? Have you got a copy of the last record that I did?

Habal:

I do not.

Brown:

I did it with my late partner, Phil Ryan, who I loved very much. He died a few years ago in 2015. But it’s a good example of, I mean, it’s different. What I’m doing now is somewhat different but related because I have a new writing partner down here. He’s another great musician, also a keyboard player, a guy called John Donaldson. And we’ve been working on most of the stuff for the new record together. He’s quite jazz-orientated. The songs are sophisticated but they’re not jazz but there’s a little bit of jazz lurking in the background. I was very surprised and also incredibly grateful because, when Phil died, we had been together since he joined my band Piblokto in 1970 and we’d been together on and off since then for many, many, many years, and I thought that nobody could ever replace him and I’d more or less given up the idea of writing stuff for myself, although I was still singing the old stuff, and then I met John and it was really great. He’s completely sympathetic and a great musician. So I’m very happy and then we gradually develop these new songs with a few other people involved, and it’s very good, it’s working very well and my publishers like it. It’s very interesting. You know we may sell a few copies.

Habal:

That’s great. Well, anyway, Pete, I want to thank you. It’s been a real pleasure and honor talking to you. Thanks again. Well, we’ll see you when the future gets here. Thanks a lot, Pete.

Brown:

Alright. Bye-bye.

Gallery

Recent Articles

Can Molly Mend Your Marriage?

•

February 16, 2026

Immer Für Immer by Flying Moon in Space–Album Review

•

February 13, 2026

Loading...