The Psych Ward–Thank Christ for the Bomb by The Groundhogs

The Psych Ward–Thank Christ for the Bomb by The Groundhogs

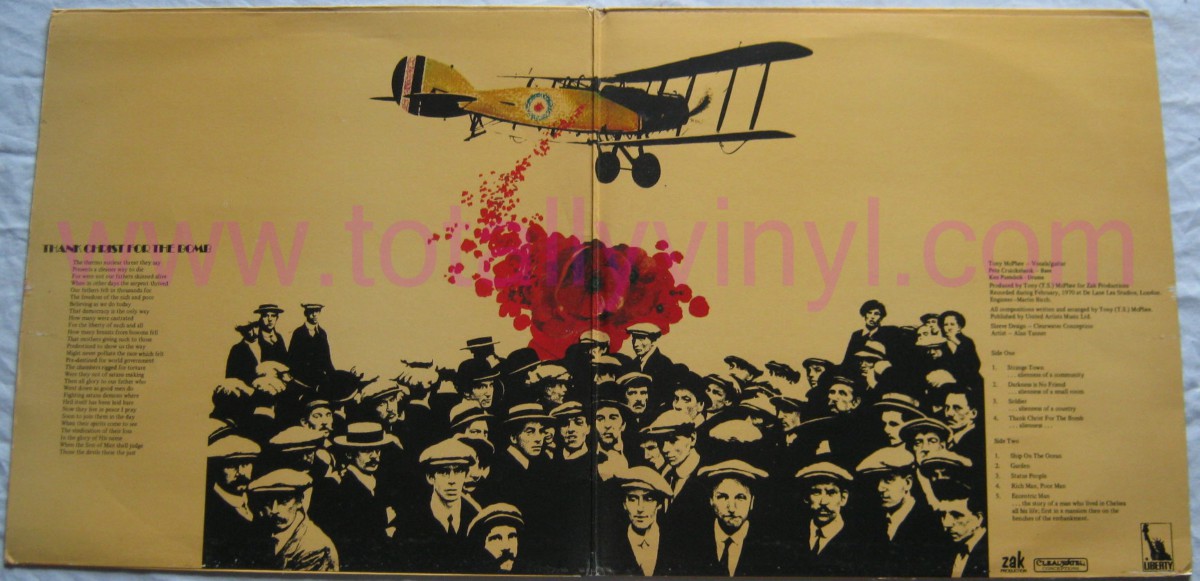

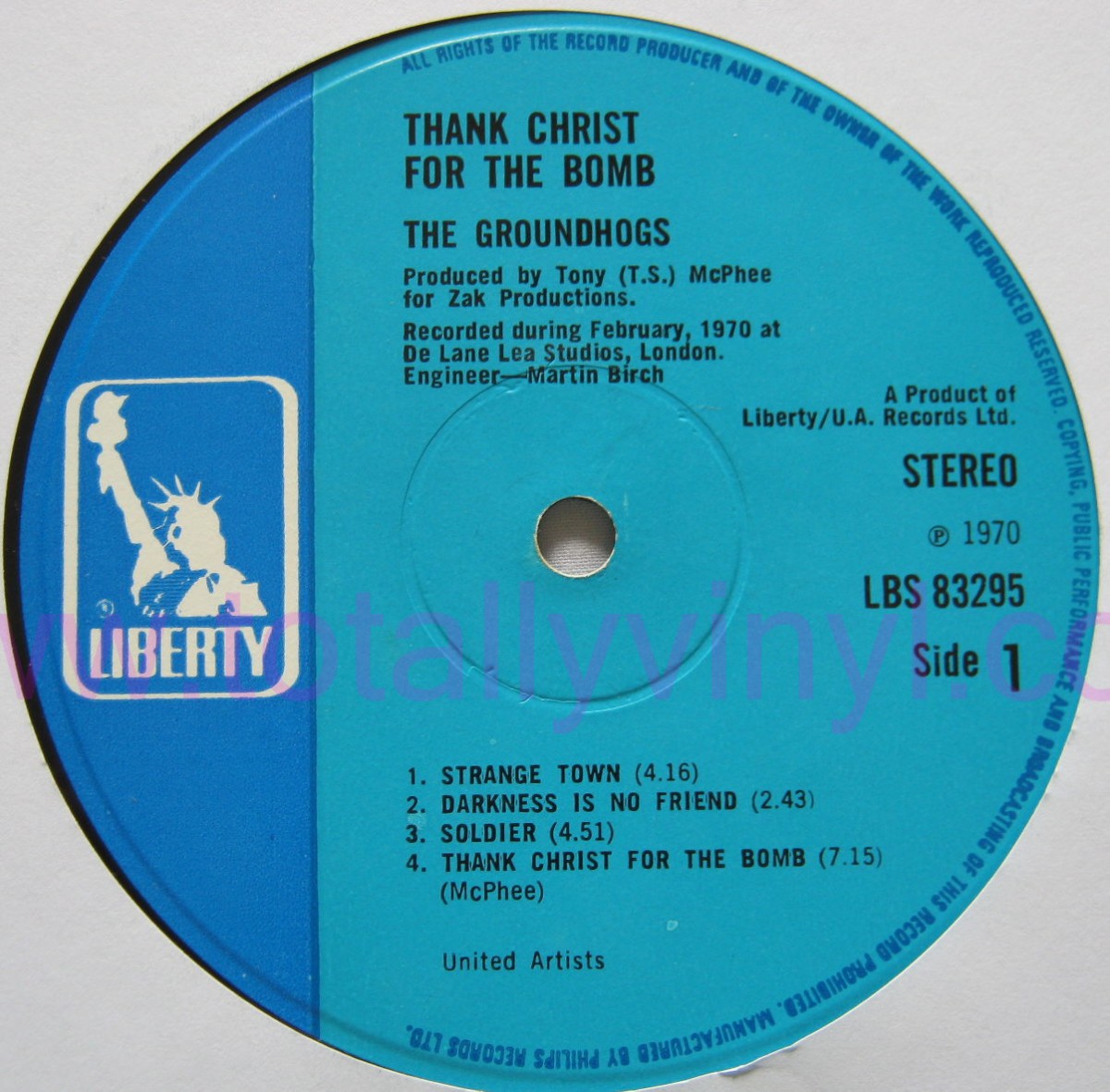

1970’s ‘Thank Christ for the Bomb’ is a concept album by British trio The Groundhogs, so-named after John Lee Hooker’s ‘Groundhog’s Blues.’ This album appeared on my radar in 2020– in Mark Lanegan’s audiobook of his starkly honest memoir, “Sing Backwards and Weep.” I’ve compartmentalized it as a find from the angsty, early days of the pandemic, but listening to it again reveals its rock brilliance, and I’m excited to recommend it.

There’s a tantalizing familiarity to this music.

Revisiting this jewel of British psychedelia, I’m struck by how well it’s aged. It never fails to give that specific, ‘I must’ve heard this before/ I’ve never heard this before!” kind of feeling. There’s a tantalizing familiarity to this music. In another world, one imagines some of these songs would be staples of classic rock radio. But at least in the US, no such luck.

In the UK, ‘Thank Christ for the Bomb’ was a commercial breakthrough, hitting the album chart at No. 9. The sound here is blues-rock, but something in its emotionally raw punch has bright-edged, psychedelic swagger.

The opener, “Strange Town”, is a blend of prog/stoner rock. Singer-guitarist Tony McPhee’s slap-back vocals establish a cool, hypnotic vibe for the album’s side one theme: alienation. It’s the kind of “othering” that speaks to the schism of the late 60’s/70’s. In this strange town:

“I don’t believe these people/ Spend all their time walkin’ round lookin’ so glum/ They think that life is for workin’ to secure their pension when retirement come”.

The second track, “Darkness is no Friend,” is a poetic call to embrace, or at least accept, the shadow. It’s rock but in a slightly theatrical, prog-forward mode. McPhee plays with the Jungian balance of things, the truth in irony:

“But I would not shut out the moonlight/ For darkness is no friend”.

And there’s also a self-aware rejection of life lived in the confines of an echo chamber:

“It’s so easy to shut your eyes/ To block out the things that you despise/ Just as easy for the dark of night/ To blot out the daylight Things that aren’t right”.

The third track, “Soldier,” feels like a cousin to “Band of Gypsy’s” “Machine Gun.” It’s another well-arranged, darkly-tinged rock manifesto. Here, the alienation is the conceit that soldiers must accept to be soldiers – the dehumanization of the enemy: “Don’t see them as men, just see them as enemies of the king, y’know.” For me, it’s somewhere around here in the listen that my ears wake to the perfection of the mix, the work of acclaimed engineer Martin Birch, who worked with Deep Purple, Jeff Beck, and Fleetwood Mac.

The titular “Thank Christ for the Bomb” begins as a single acoustic guitar song, accompanied by McPhee vocals, pointing to the core of a stalemate that’s existed since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, at least in some sense:

Everyone’s scared to obliterate/ So it seems for peace we can thank the bomb/ So I say thank Christ for the bomb.”

That’s a darkly pragmatic aphorism and one that’s certainly familiar to every defense department on the planet. It’s the essential dark irony that only the threat of total annihilation seems to check the escalation of hostilities in a perpetually cold-warring world. All of which hints at the edges of the psychedelic experience, wherein one may tap into the preciousness of life, feeling how vital its preservation feels, and all the more so at the precipice of nothingness.

“Ship on the Ocean” feels like a generational predecessor to Queens of the Stone Age’s “I Never Came,” sharing 3/4 of the same chords in succession and then seeding elements of that melody throughout the song. Here, McPhee admits to the tyranny of desire:

“It’s not my body but my mind I can’t control/ I have everything I need but still… I want more”.

The sixth song, “Garden”, has a hazy, desert rock edge as contemporary as a trip to the dispensary. The liner notes say that side two of the album is “the story of a man who lived in Chelsea all his life; first in a mansion, then on the benches of the embankment.” It seems that the character is proposing to embark on the “drop out” phase of (Leary’s) psychedelic triumvirate:

“When I leave this house I’m going to stay/ I’m forsaking my comforts to live another way/ Get my clothes from heaps, my food from bins/ My water from ponds and have tramps for all my friends”.

“Status People,” has an all-time great, iconic, and powerful bass-riff/octave guitar refrain. McPhee sings across the lines masterfully, the protagonist of side two telling us:

“I’ll be glad to say goodbye/ To status people who are just a lie/ I left them behind when I walked out the door/ I’ll never see them anymore”.

Number eight, “Rich Man, Poor Man,” recalls a mixture of 70’s rock riffology from various rock bands. It’s a little like some of the music on The Who’s Tommy. Again, the same character drops further into dropping out:

“You can be the rich man, I’ll be the poor man/ Cross section of mankind You can have society, I’ll take nature/ Combined with peace of mind”.

The closer, “Eccentric Man”, could be a Masters of Reality heavy, sludgy, headbanger. There’s a fuzzy timbre here that’s ahead of its time and guitar licks that sparkle timelessly. Oh, and it turns out the protagonist is a proto-Chris McCandless:

“My bed is a park bench and my sheet and blankets are newspaper pages/ The people think I’m crazy but I know I’m wiser than all the sages/ ‘Cos I have money they think that I’m a fool for doing what I do, but I know it’s right”.

The album is an odd dive, but even if the lyrics are confounding in places, the music is as lively and contemporary as you could want from something made in 1970. “Thank Christ for the Bomb” reveals an awesome potential: Great discoveries in the annals of rock may still be out there, and perhaps we’ve never heard some of the heaviest riffs of the 20th century.

Gallery

Recent Articles

Loading...