Acid Lore: Mickey Mouse LSD

Acid Lore: Mickey Mouse LSD

He gives the kids free samples,

Because he knows full well

That today’s young innocent faces

Will be tomorrow’s clientele.

‘The Old Dope Pedlar’–Tom Lehrer

In the early 1980s, dire warnings were issued to parents around the USA. Lick and stick ‘tattoos’ with colourful pictures of Mickey Mouse in full Sorcerer’s Apprentice garb were distributed free to children. The transfer tattoos were impregnated with LSD and merely handling them, never mind licking them, would send the child on a potentially fatal acid trip. Unscrupulous drug dealers were giving these tattoos away to children to introduce them to mind-warping psychedelic drugs. Even worse, some of the tattoos were laced with strychnine. Many children had already fallen victim and were being treated in hospital. Some had died…

The Mickey Mouse Acid myth (also known as the Blue Star Acid legend) is one of the most studied pieces of drug lore. It emerged in the early 1980s and was quickly debunked, but the legend was too good to die. The myth has depraved drug dealers wickedly targeting innocent children. It involves a mysterious and frightening mind-altering drug. And, at a time when Disney was known for its conservative family-friendly image, it subverted its most iconic character.

The myth was a regular newspaper scare story well into the early 2000s but seems to have died a death in recent years. So, where did this myth come from, what made it so persistent for so long, and where did it go?

DO NOT HANDLE!!!

The Mickey Mouse acid legend began as Xerox lore. In 1980, these typed and photocopied warnings would appear on noticeboards in schools, hospitals, offices, and other public buildings. Easy access to Xerox machines meant they could be copied at will and the message spread about this appalling new menace to society – children’s transfers dripping with LSD.

The messages made liberal use of exclamation marks and all caps as they warned of these drug-laced transfers. Many had a crudely drawn image of Mickey Mouse in a pointy magician’s hat (based on his appearance in Fantasia) to alert concerned parents what to look out for.

RELATED: LSD is Laced with Strychnine!

Sometimes the flier would be retyped with more horrifying details added – now the transfers also contained strychnine and many children had died from using the stickers. Often, a school, hospital, or local government office would put their stamp or an authoritative signature on the warning, thus its credibility was enhanced. This was often when the press would pick up the story and print it, often uncritically.

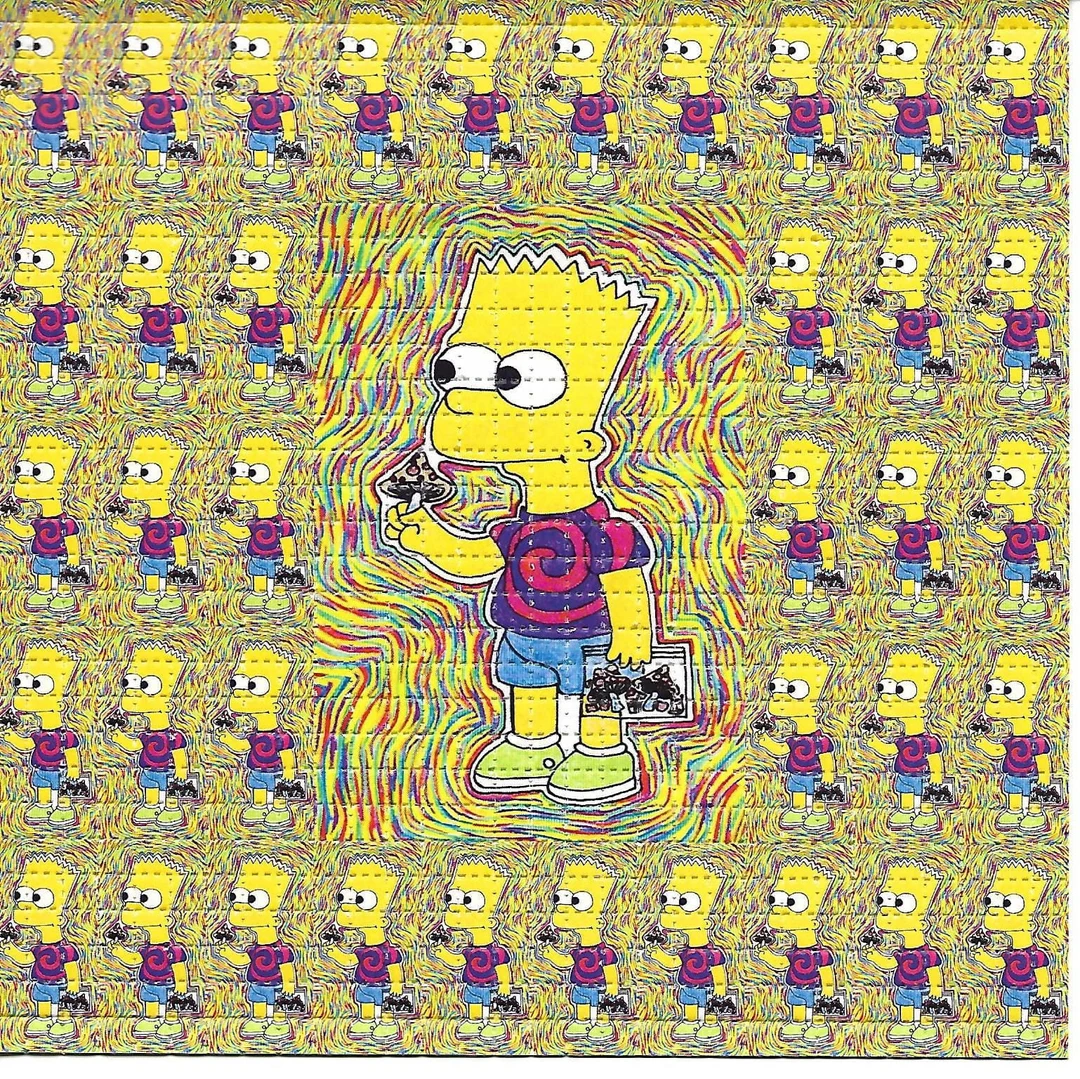

Over the years, the cartoon character depicted on the acid tabs might change, though Mickey was almost always a part of the warning. Sometimes the transfers had images of Superman, Bart Simpson, or a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle. Dealers, it was claimed, were doing this to deliberately attract children as customers.

Goofy

Indiana Journalist Jim Quinn thought the story began as a police noticeboard bulletin informing officers that LSD sometimes came in the form of stamp-like blotters with colourful images. These might be attractive to children who could mistake them for a transfer tattoo. This message was then retyped in garbled form from memory by concerned citizens and spread far and wide, with more details added along the way. The photocopier was what gave this myth wings. The fact that it was printed and apparently came from an authoritative source such as government officials, local health workers, schools, or police departments gave it more credence – even though named officials on the document were often spurious.

Further contributing to the myth was the fact that LSD frequently came in the form of blotters, little square tabs that featured colourful designs, including cartoon characters. The August 1981 edition of the counterculture magazine High Times ran a cover story about a limited-edition bundle of LSD tabs that featured Mickey Mouse in a wizard hat and coat. Some anti-drug campaigners took this as evidence that the LSD tattoo story was true, and police raids found blotter acid with cartoon figure designs.

The Mickey Mouse acid myth reflects our fear of contamination, the corruption of innocence, and concern about LSD driven by two decades of lurid and sensational press coverage about the drug. The concerned citizens who photocopied the fliers and handed them out to all they knew thought they were doing the right thing, and the printed page with its official stamps and signatures masked its absurdity. For one thing, selling LSD to children would be very unwise for a drug dealer. Children don’t have any money to buy drugs once your evil plan to get them hooked has succeeded. And secondly, the risks would be extremely high. Furthermore, the idea that merely touching the ‘tattoos’ could send one on a fatal trip is also ridiculous.

Mickey Takes a Trip

Despite this, the myth was highly successful, aided by the increasing availability of photocopiers, word processors, and email. From the USA, versions of the Mickey Mouse acid leaflet quickly spread to Canada, where it was translated into French and, a few years later, was found all over France. A 1991 survey of 1000 French adults by the Foundation of Rumour Study found that one in five had read the leaflet and that 48% of the sample had read or heard about it. This is the kind of coverage advertisers dream of, especially considering that two-thirds of the people who had read the leaflet assessed that it was believable – a success rate that puts professional advertising campaigns to shame.

The leaflets circulated through Britain in the 80s, resurfacing every few years in the media. A nice example of how the leaflets spread was reported in the Liverpool Echo in 1989. A Lancashire nurse was on holiday in South Africa when she was given the Mickey Mouse acid flier and so brought it home with her. She thought that people should know about this danger, so she made copies of the warning and gave it to parents she met at Ormskirk Hospital where she worked. Parents took copies to their offices and put them on their noticeboards. Children took copies to school and teachers used them in lessons about the dangers of drugs.

Although newspapers frequently dubbed the story a hoax or an urban legend, the myth was more attractive and memorable than the rebuttal. The regular debunkings in the media were quickly forgotten the next time another version of the leaflet came around. In England in 2001, police and local media accused Bedfordshire council of ignoring the menace of acid tattoos targeted at children because the council had said the leaflets were a hoax and refused to issue a public warning about them.

By the early 2000s, reports of Mickey Mouse tattoo acid seemed to dry up. Perhaps it just wasn’t plausible anymore. Increased scientific and medical interest in psychedelics meant LSD was losing its stigma as a drug of abuse and a threat to the youth. Other drugs were now filling that role. The stereotype of the seedy dope dealer hanging around the schoolyard now seems rather quaint. People are nowadays less likely to believe spurious hand-typed, misspelled copies of sensational warnings stuck on noticeboards. Scare stories and urban legends now have the internet and social media, a perfect environment for them to thrive and spread.

Even today, we can see a distant echo of the Mickey Mouse acid legend in the modern fear that Halloween candy is being laced with fentanyl by sinister dealers wanting to catch their clients young…

Gallery

Recent Articles

Vinyl Relics: Fields by Fields

•

February 10, 2026

A Tale of Crescendo ~ Epilogue

•

February 7, 2026

Loading...

Vinyl Relics: Would You Believe with Billy Nicholls

- Farmer John

1 thought on “Acid Lore: Mickey Mouse LSD”

The Mickey mouse LSD was really good clean acid. I was there, Santa Cruz. I saw the two guys in leather jackets brought boxes of it to my buddy Tom. I don’t know where they came from Oakland or SF ? I connected Tom to my buddy Charlie. Charlie was on the History Channel twice. The spread of the Mickey blotter went nationwide. They then made Donald Duck and Goofy. I think it was Sandoz Lab LSD It was clean and a person could take a lot.