Drug Addiction Treatment

Drug Addiction Treatment

Ibogaine, Still Illegal, Is by Far the Most Effective Remedy

Drug and substance use is as old as humanity itself. Throughout history, it is easy to see that our ancestors had a taste for psychoactive substances, which has remained a constant– present in every culture from every period in all areas of the world. Historically, psychoactive substances have been used by several different social groups. Everyone from priests/religious sects who used vision-inducing psychoactive substances for religious ceremonies (i.e., iboga and ayahuasca) to healers that relied on many potent plant alkaloids for medicinal purposes (i.e., opium) to the general population as a way of relaxing and forging strong social bonds (i.e., alcohol, kava, and caffeine). For the first few thousand years of recorded history, there is little mention of the use or overuse of a range of substances aside from alcohol. Whether this was a function of a lack of supply or of cultural normalization, the issues people may had with addictive substances went largely unnoticed or were not recorded.

What can be said with certainty is that the issues that can accompany substance abuse, much resembling today’s concept of addiction, were already being discussed in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. From then, it became abundantly clear that almost every substance that can cause a change in mental status or perception was or had been abused to the point of causing negative social and personal issues.

Due to the conquistadors’ lack of understanding and exposure to such ceremonies, they perceived this literally as devil worship.

Subsequently, a combination of perceived, negative cultural and social impacts, followed by a lack of historical context and a hefty dose of racism, would create the perfect storm in which the repeated prohibition of mind and mood-altering substances was all but inevitable. A great example is when the conquistadors reached Mesoamerica. They were overcome with horror when they observed the indigenous people participating in ritual ceremonies that included blood sacrifices and consuming what they referred to as “The Flesh of the Gods,” aka psilocybin-containing mushrooms. Due to the conquistadors’ lack of understanding and exposure to such ceremonies, they perceived this literally as devil worship. Coming from a predominantly Christian background, the Spaniards saw this as evil, so they did everything they could to obliterate all traces of the practice.

Unfortunately, this prohibition scenario would play out repeatedly all through history. These perceived negative, cultural, and social impacts have manifested in a highly undesirable stigma surrounding the consumption of these compounds regardless of their potential benefits. Not only has this slowed research in addiction medicine, but it has almost entirely frozen the evolution of treatments like psychedelic therapy. Even though psychedelic therapy was seen as a major leap forward in the treatment of addiction and mental health in the 1950s and ’60s, it was almost completely abandoned due to the harsh regulatory issues that reflect this stigma. For decades, this made trying to do research almost completely impossible.

The Stigma Persists

Europeans and Westerners have woven a highly negative narrative surrounding substances that alter consciousness. This becomes crystal clear when you look at the definition of addiction, which, according to the American Society of Addiction Medicine, is when a person who “uses substances or engages in behaviors that become compulsive continues despite harmful consequences.” It is easy to spot the distinctly damaging connotations implicit in this definition. With only one word, “addict”, a person can find himself defined by a whole host of destructive ideas– some merited, some not. Certainly, no one wants to be associated with criminality and a lack of personal control over most aspects of their lives. Furthermore, this nomenclature not only feeds the stigma, it also makes it exceedingly difficult to receive proper treatment and lead a productive life.

According to the Mayo Clinic, a few common symptoms of drug and alcohol addiction are:

- Feeling that you must use the drug regularly — daily or even several times a day

- Having intense urges for the drug that block out any other thoughts

- Needing more of the drug to get the same effect over time

- Taking larger amounts of the drug over a longer period than you intended

- Making certain that you maintain a supply of the drug

- Spending money on the drug, even though you can’t afford it

- Not meeting obligations and work responsibilities, or cutting back on social or recreational activities because of drug use

- Continuing to use the drug, even though you know it’s causing problems in your life or causing you physical or psychological harm.

Some common withdrawal symptoms are:

- Trembling and tremors

- Muscle pain or aches

- Hunger or loss of appetite

- Fatigue

- Sweating

- Irritability and agitation

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Confusion

- Insomnia

- Paranoia

- Seizures

- Dilated pupils

A Historical Look at the Standard Practices for Addiction Treatment

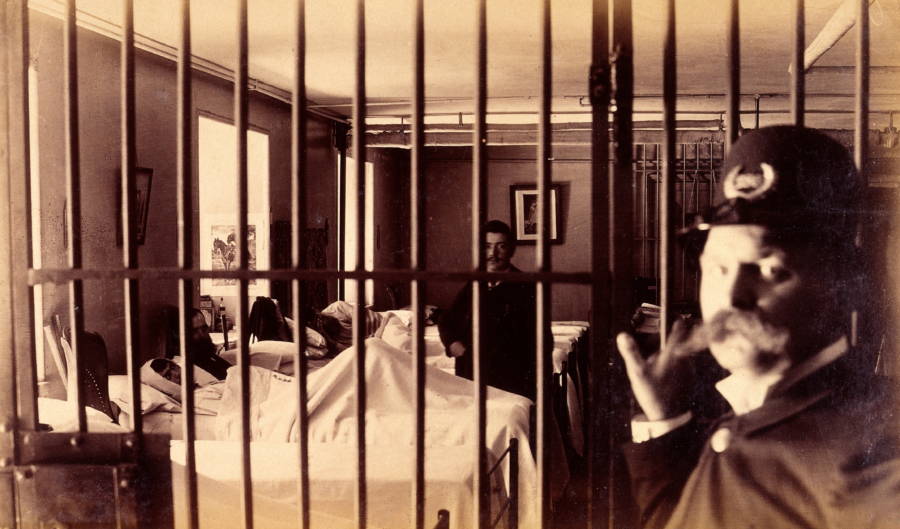

Opened in 1850, Lodging Homes and Homes for the Fallen can be considered the first sober living houses. These homes provided short, voluntary stays that included non-medical detoxification, isolation from drinking culture, moral reframing, and immersion in newly formed sobriety fellowships. These first rehabilitation homes were modeled after state-operated insane asylums.

Although these places were a step in the right direction, they did not offer much in the way of medical detox or help. These early treatment options relied heavily on white-knuckle sobriety, that is, getting off and staying off drugs through sheer willpower. Around the 1890s, this progress was reversed due to de-medicalization and criminalization of alcohol and drug problems. Soon the standard of care for addiction and withdrawal symptoms was reduced to city drunk tanks, public hospitals, and insane asylums.

It took the better part of 100 years for things to begin shifting from a punishment mindset to a treatment-oriented model where long-term recovery was the goal. This change began in 1952 when the American Medical Association agreed to define alcoholism as a chronic disease. Although it took until 1987 for the AMA to classify all drug addictions as diseases, the classification of alcoholism was an essential first step that paved the way for the standard model of care and treatment for addiction today. Without this, all the medical interventions that are now standard practice would never have been explored.

Drug and Alcohol Addiction Treatment Today

Addiction treatment has come a long way in the last fifty years. For starters, treatment has become more accessible with the passage of The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, as well as The Affordable Care Act during the Obama administration. Both of these require insurance companies and group health plans to treat addiction more like they would any other disease. Additionally, as more research is conducted, and scientists develop a deeper understanding of addiction, recovery options have become increasingly available.

Treatment today can be broken down into two categories: the treatment of underlying mental and emotional issues through various forms of therapy, and the treatment of withdrawal symptoms.

Therapy as a Recovery Tool

There are a few types of therapy options and programs that exist to help people going through withdrawal and recovery. Therapy sessions in both group and individual settings, including groups such as the 12-step groups (Alcoholics Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous, Heroin Anonymous, etc.), faith-based recovery groups (Celebrate Recovery, Reformers Unanimous Recovery, Teen Challenge USA, etc.), and Cognitive Behavioral groups (Life Ring, Smart Recovery, etc.). Individual therapy serves two main functions, to provide support and offer guidance during challenging times and to help the patient work through issues and emotions that could trigger people and their substance abuse. Recovery groups serve as a community of like-minded people who have gone through similar challenges. Their experience allows them to offer emotional support and relevant insight to the patient, relieving feelings of isolation and providing a role model for recovery.

All support groups, despite having differing core beliefs, use almost identical methodologies and approaches to recovery. Each is based on a step-by-step process that includes asking for and accepting that you need help, dealing with issues from your past, making a daily attempt to be conscious of your actions, and striving for self-improvement. These act as guidelines for achieving and maintaining a happy, healthy, and productive life after addiction.

Medically-Assisted Drug Withdrawal and Detox

The second category of treatment revolves around medical interventions. Commonly referred to as Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT), this method focuses on using medications to assist in the process of severe withdrawal and maintenance therapies, such as replacement and anti-abuse medications.

Medications commonly used in the treatment of acute withdrawal can be split into a few main categories: non-narcotic pain medications (Tylenol, NSAIDs, and muscle relaxants) to help take the edge off the pain that is associated with withdrawal, non-narcotic anti-anxiety medication (Clonidine, Librium, and other beta-blockers) to ease intense bouts of anxiety, non-narcotic sleeping medications (Remeron, Trazodone, etc.) to treat insomnia, and antidepressants and antipsychotics to help treat any acute or preexisting issues such as depression, mood imbalances, and hallucinations.

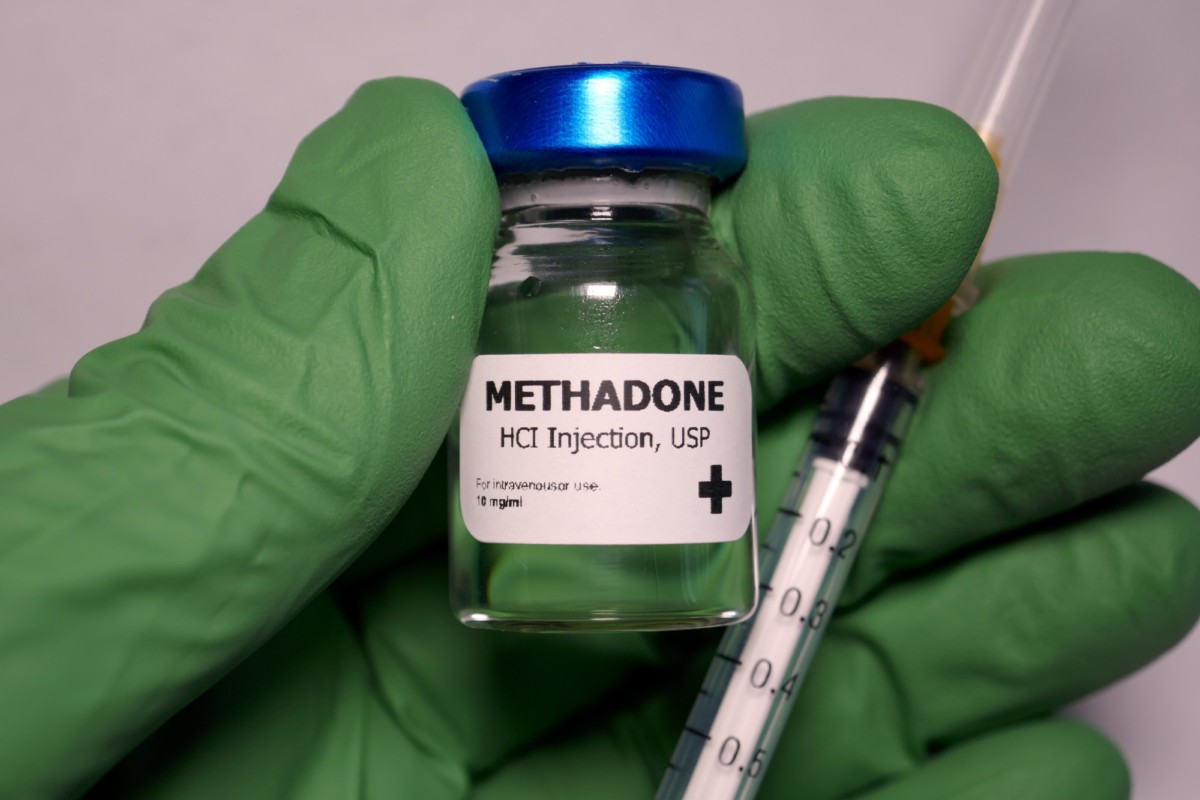

Two of the most well-known and used maintenance medications are Methadone for opioid addiction and Disulfiram, known as Antabuse, for alcoholism.

Methadone, despite historically being used as a pain medication, was approved by the FDA in 1972 for its use as an opiate withdrawal treatment. As a slow-acting opioid agonist, having a half-life of 24 hours. Methadone has shown to be an effective replacement therapy that also has the benefit of a once-daily dosage that can be given in a clinic under direct supervision to reduce the possibility of diversion and abuse.

Opioid agonists can be taken orally or by a subdermal implant, which releases the drug continuously over a period of up to 12 weeks, which makes consuming alcohol almost impossible. If someone taking such a medication uses alcohol, they will experience effects like a severe hangover for possibly the next several hours. Symptoms include flushing of the skin, accelerated heart rate, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, throbbing headache, and visual disturbances. Although this will not physically stop people from being able to drink, it will make drinking so unbearably painful that many will develop an aversion to alcohol.

Medically-assisted detoxing is a way for addicts to ease withdrawal symptoms that could be extremely uncomfortable and painful if they were to quit “cold turkey. Traditional treatments for addiction and withdrawal still carry a high risk of relapse. Often the focus remains on just quitting the substance instead of delving into the deeper issues associated with their persistent substance abuse.

According to researchers at the University of Chicago, “the major drug-treatment modalities,” such as MAT, therapeutic communities, and outpatient programs, “have all been shown to be successful by most outcome criteria.” They highlight that, “programs with flexible policies, goals, and philosophies produce better results than inflexible programs, especially when they adopt combinations of treatment components suited to individual clients’ problems and needs.” It stands to reason that people suffering from addiction can only benefit from having more tools at their disposal.

Holistic Treatments for Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal Symptoms

The current gold standard of addiction treatment uses new medications like buprenorphine and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy which can be used in the treatment of opiate addiction, alcoholism, and possibly other addictions as well. These advances in addiction medicine offer more hope to those struggling with dependance issues. Although this progress is quite promising and some of the stigma surrounding addiction has slowly lifted, current treatments still have relatively low retention and overall success rates. To better serve people struggling with addiction, many have decided to turn to a holistic model of treatment.

Holistic treatment is a term that is loosely defined and can encompass several methods. For this article, let’s define holistic treatment as the treatment of the person as a whole, focusing on physical, emotional, and spiritual issues that are both a symptom and the possible cause of addiction.

A perfect example of holistic treatment is psychedelic therapy. Not only can specific plant medicines help treat acute withdrawal, but they also help heal the brain through various mechanisms and give the patient perspective on old issues that may have ultimately paved the way for addiction. A perfect example of a psychedelic that possesses all these traits is Iboga. Iboga and its primary alkaloids, ibogaine, and noribogaine, have been studied extensively.

According to multiple case reports in a meta-study published by the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, “individuals [who] were treated for opioid withdrawal with a single oral dose of ibogaine [700–1800 mg] in a nonmedical setting […] the report states that all seven participants showed an immediate reduction of opioid withdrawal symptoms.” Alone this fact is quite impressive, and anyone who has been addicted to opiates will tell you it is quite the godsend. Being able to avoid the worst withdrawal symptoms is the holy grail of addiction medicine. To further add to just how unique these compounds are, the study also showed that, “three of them (the patients treated) remained abstinent for at least 14 weeks.” There is no intervention that is currently offered by doctors that can even come close to the statistical efficacy of ibogaine.

Putting ibogaine aside, other psychedelics, specifically LSD and psilocybin-containing mushrooms (magic mushrooms), also show great promise in treating addiction. The literature indicates that psychedelic therapy with these substances has two main ways of affecting a positive impact on the patient’s life. The first is through a mystical experience, which can occur with standard to high doses of psychedelics. The second is the benefit that can be gained when a patient doses small amounts of psychedelics over a long period, commonly referred to as microdosing.

The research on mystical experiences clearly shows through “qualitative studies and anecdotal reports […] that mystical-type experiences can have profound and lasting positive after-effects.” During the studies in anecdotal reports, they found that people who had mystical experiences reported that “there remains the joyful impression of having encountered a higher reality and discovered new truths. Common concerns recede in importance or appear in a new light, and new beliefs and values take the place of old ones. Some patients report feeling intensified love and compassion for others, and many say that life as a whole has taken on new meaning.”

Looking at this through the lens of addiction, it is easy to see how an experience like this can be helpful in overcoming deeply rooted mental blocks and preconceived notions about themselves and others that may hold a person back and keep them locked in negative patterns of thinking.

While it is not advisable for everyone, particularly those with a history of severe mental health issues like psychosis or schizophrenia, to take high doses of psychedelics, there is still a way patients can benefit from psychedelics without the risks associated with a large dose. This can be done best through microdosing. When a patient takes low doses of drugs that activate the serotonin-2A (5-hydroxytryptamine-2A; 5-HT2A) receptor, as most psychedelics do, a process known as neurogenesis is turbocharged. Microdosing is much safer as the patient takes sub-perceptual doses of the substance. This removes the possibility of having a “bad trip” which could cause further mental and emotional issues if the person is either high risk or in an uncontrolled setting.

The way microdosing works is that it causes an increase in BDNF or Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. BDNF is a protein directly responsible for the regrowth and regeneration of nerve cells, particularly those in the brain.

So, the more BDNF is present, the more actively your body can repair and regrow nerve cells. This is one of the reasons microdosing is receiving so much attention from the scientific community, specifically those in the field of addiction medicine. I can help repair a patient’s brain from drug use instead of just treating the associated symptoms.

Unfortunately, despite the apparent benefits of psychedelic therapy, adopting these tools has been painfully slow. The main reason for this is the same reason the field of addiction medicine has been so stunted, the stigma surrounding drugs and drug use. Not only is there the standard barrier that the stigma perpetuates, but people are also incredibly resistant to the idea that “recreational” drugs may help treat addiction.

The science supporting psychedelic therapy grows with every trial that is done. Given this fact , doesn’t it make sense to use every available tool in the treatment toolbox?

- White, W. (1998). Significant Events in the History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America.

- Kelly, J. (2016). Is Alcoholics Anonymous Religious, Spiritual, Neither? Findings from 25 Years of Mechanisms of Behavioral Change Research. Addiction, 112(6), 929-936.

- M. Douglas Anglin, and Yih-Ing Hser (1990). Treatment of Drug Abuse. Crime and Justice, Volume 13.

- Patrick Köck, Katharina Froelich, Marc Walter, Undine Lang, Kenneth M. Dürsteler (2022). A systematic literature review of clinical trials and therapeutic applications of ibogaine. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, Volume 138

- Lutkajtis, A. (2021). Entity encounters and the therapeutic effect of the psychedelic mystical experience. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, Volume 4, Issue 3

- Hutten, N. R., Mason, N. L., Dolder, P. C., Theunissen, E. L., Holze, F., Liechti, M. E., … & Kuypers, K. P. (2020). Low doses of LSD acutely increase BDNF blood plasma levels in healthy volunteers. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science. Volume 4, Issue2, 461-466.

Gallery

Recent Articles

Unicorn by Rio Kosta–Album Review

•

February 24, 2026

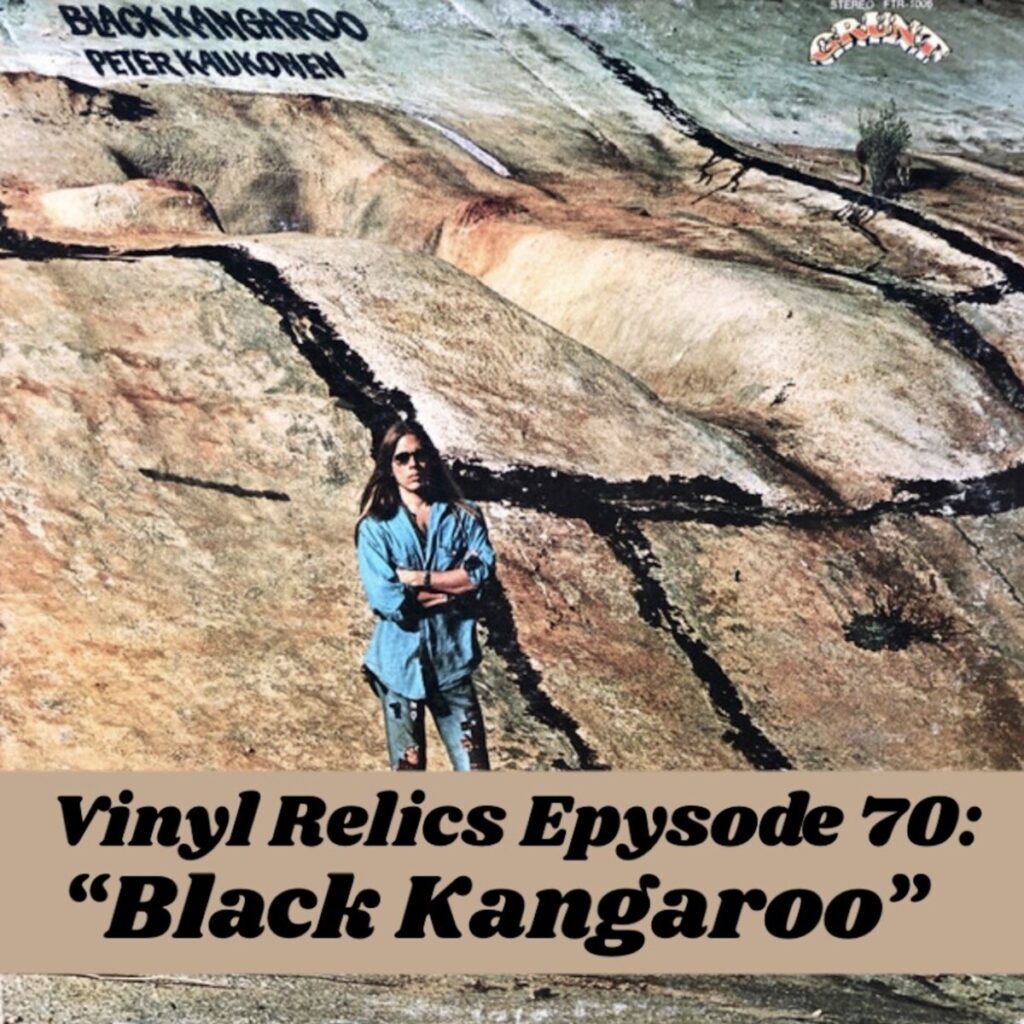

Vinyl Relics: Black Kangaroo by Peter Kaukonen

•

February 21, 2026

Loading...