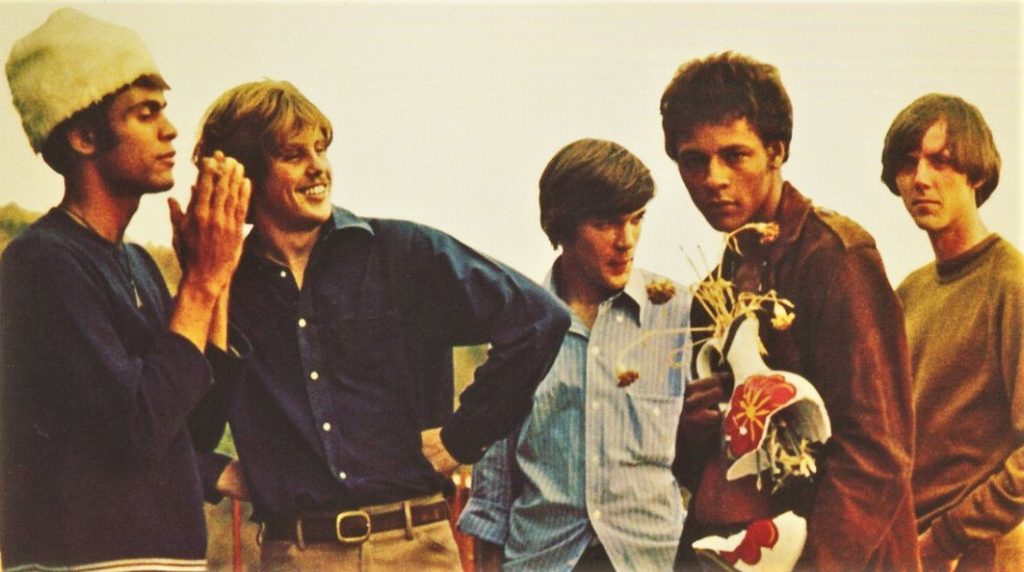

Interview with Johhny Echols of Love

Interview with Johhny Echols of Love

LeValley: I’m Jason LeValley with Psychedelic Scene, and I’m here with Johnny Echols from the band Love. Johnny. Thanks for being here.

Echols: That’s my pleasure. Thanks for having me.

LeValley: So, you knew Arthur Lee when you both lived in Memphis?

Echols: Correct. Yeah. Our families were actually my grandmother and his mother. She was a little older when he was born. They were best friends in high school, and then they were schoolteachers together. So actually, we go back to before my mother was even born. My grandmother and his mother were friends. So, our families go back a long way.

Echols: And he was basically like my big brother most of my life, you know, growing up. He was, you know a couple of years older. So yeah, we’ve known each other or knew each other quite some time.

LeValley: So his family moved to LA before yours, I think. Right?

Echols: Correct. Correct. Yeah.

LeValley: And did you keep in touch with him?

Echols: No. At that point I was still a little kid, so we just happenstance of serendipity. We wound up, moving to the street to Los Angeles, and winding up a couple of doors down from them. It was just totally by chance that we ended up in the same neighborhood just a couple of doors from each other.

LeValley: Wow! It’s fate.

Echols: Yeah, it was fated. Yeah. So, we continued our friendship, which remained until he passed. And we’re still friends, even though it’s on a different plan. So.

LeValley: Yeah.

LeValley: So how old were you when you joined his band, which I think was called the Grassroots?

Billy Preston and I were good friends. We went to high school together, and we started the first group.

Echols: Well,actually, no, we started. I’ll have to go back a little further. Billy Preston and I were good friends. We went to high school together, and we started the first group. It was called Billy Preston and the Soul Brothers, and then it was just called the Soul Brothers. And, let’s see we had the House Rockers also, and Arthur came to one of the high school assemblies. You know the little talent shows and things, and he saw Billy and I playing, and all the attention we were receiving from the young ladies in the audience, and so that got him interested in joining the group. Now, he had taken accordion lessons. You know, these guys who go door to door giving teaching lessons. And you’re buying the instruments. Basically, they’re selling the instruments, and the lessons go with it.

Echols: And so he took accordion lessons. But at that point he was not really that good, because he really didn’t practice that much, but he could play a little bit on the Conga drums and bongo. So, he just joined our group, basically as a kind of semi percussionist, so to speak.

LeValley: Are you talking about Billy Preston?

Echols: Yes, Billy Preston. Billy Preston. Yes.

LeValley: That’s amazing! I didn’t know he factored into your story at all.

Echols: Oh, yeah, yeah, he’s big time in our story, because we started together. And I played with Little Richard when I was a kid. We both did, and as I said, when Arthur heard that he wanted to join, so he joined our group, and we played and did fraternity parties, and up and down the West Coast, and then at some point, Billy’s gospel career was taking off, and he was selling a lot of gospel records. So, Arthur kind of took its place, even though Arthur was nowhere near the organist or keyboardist that Billy was. You know, Billy’s an absolute. He is a real genius, I mean, it’s not a bullshit genius. He is a really perfect pitch genius. He could hear something one time and write every single note down with the accents and everything perfectly, and then play it. That’s how good he was.

LeValley: Is he somebody that you’ve kept in touch with?

Echols: I did. And, of course, Billy passed away. But yeah, we kept in touch for years and years. Yeah, and played from time to time, and we met The Beatles together. And when I was in high school, we did a tour of England with Little Richard, and met The Beatles, and they were kind of like little schoolboys running around chasing Richard. I mean, they were just infatuated with him, and they just loved him so much, and so…

LeValley: So, what year would that have been?

Echols: This would have been 1963, I believe.

LeValley: Wow. Okay.

Echols: And, you know, I was still in in high school then, and we got back here, and a courier came to one of the clubs we’re playing, I think, at the Nightlife Club, I believe, and he brought these tickets–backstage passes for us at the Hollywood Bowl.

Echols: Now, at that point I didn’t realize, and neither did Billy, or at least he didn’t let that on to me that he knew who these guys were– who The Beatles were. We didn’t realize these were the same guys, The Quarrymen, or whoever, that used to follow Richard around, you know, it took us a while to finally realize that they were this group everybody was hearing about. So we go to the Hollywood bowl and we’re backstage. And we see them again, of course, and we realize they’re the same guys. And it was just that at that point everyone knew exactly what they wanted to do. And that was to play music. Because here these guys are up on stage, and there’s a whole, probably 10,000 screaming women and girls. And it was just mind blowing. So yeah, it was really, really fascinating.

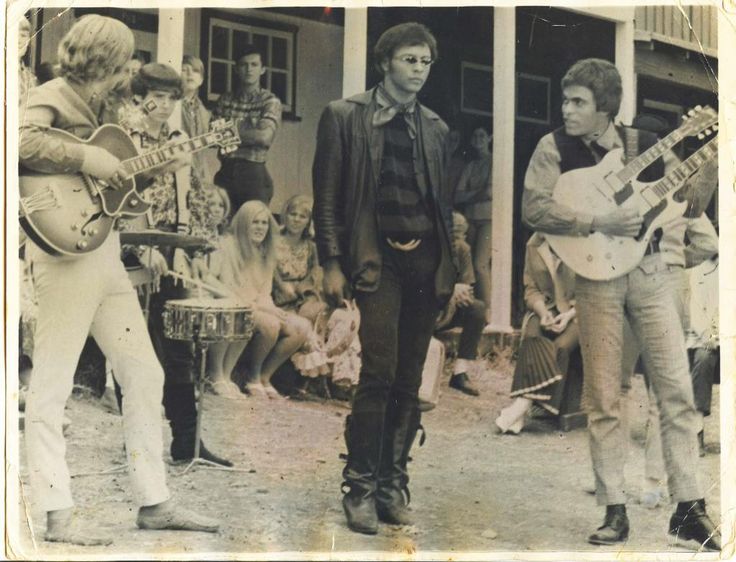

LeValley: Yeah, wow, okay. Well, what was it like working with Arthur and just being in the band Love?

Echols: Well, we have many different groups we had before that. The Grassroots was my group actually, and Arthur played with Nooney Rickett at the time, and we were playing at a place called the Brave New World in Hollywood, and Arthur was on break with Nooney’s group. They were playing up in Reno.

Echols: And he came down and saw us and said, “Wow, man, I really dig what you guys are playing. So, I’d like to join your group.” So he left Nooney Ricket and came with us, and so we started playing at this place, the Brave New World, and we played there a few months and picked up a pretty good following, and then we moved over to Via Litos and Lou Adler, producer Lou Adler came down one time to see Bryan and I. We were on break, and he was telling us how great we were, and how we were going to be the next Beatles, and how much he could. Now we didn’t know who the hell he was. But there’s this drunk guy with a chick, and I think he’s trying to impress her more than he was trying to sign us. So anyway, he talks to us a while, and then we realized, you know, our break is over. We need to go back and play, so we didn’t do it diplomatically, or whatever we said something to him like you need to speak to our management.

Echols: and for some reason he took that the wrong way, and the next thing out of his mouth is, you’ll never work in this town again. Do you know who I am, and we didn’t know who he was. So, we just thought, ‘there’s this drunken fool.’

Echols: Anyway. A couple of months later one of the people that came into the Brave New World said, we heard your record on the radios.

Echols: We don’t have a record. And they said, ‘Yeah, Mr. Jones, that’s what they called it, Mr. Jones. It’s a Bob Dylan song, and it’s done by The Grassroots. And sure enough, we go to Music City, and there’s a single released by The Grass Roots now, with Lou Adler as the producer on Lou’s label, so Lou had nothing to the madness. It wasn’t just to diss us and get back at us for dissing him.

We didn’t realize these were the same guys, The Quarrymen, or whoever, that used to follow Richard around.

Echols: He knew that if, because we were drawing huge crowds, and if they thought that was our records, the kids would run down and buy it, which they did. And Wallichs Music City was one of the… See, they didn’t have computers back then. So, it was one of the places that if you were selling well there and it would go, you know, toward which record is doing well. The Hot 100 and the charts were compiled from the sales at places like Wallichs. Music city. So yeah. Grass Roots song, I think it’s. Is it? “Positively 4th Street”? Is that the one that’s Mr. Jones knows something’s happening, and I think that’s what it is. But anyway, it went up to probably number 2 or 3 in the Los Angeles area.

LeValley: Dylan, cover.

Echols: Yeah. The Dylan cover.

LeValley: Okay.

Echols: As I said it was, it would be presumptuous of us to think that that was the only reason that he did that, but you know.

Echols: He did choose to steal our name because he knew our name was the Grassroots. It was right outside the building that he came, and you know, and he had come by there from what he said a few times and heard his place. So, he knew the Grassroots. The name Grassroots was already taken, and we had what was called a poor man’s copyright, and that’s when you send a registered letter to yourself with the name and all of that, and if you don’t open it, the judge and the court opens it, and see who has 1st claim to the name, and

Echols: we had spoken to attorneys about it, and they said you’d probably win. But this guy is such a big shot in the record industry that you’d be destroying any chance you would have of ever signing with a big label. So, we ended up deciding to change our name. So that’s how we became Love.

LeValley: So the first love album came out when…in 1966?

Echols: ‘66. Yeah, we recorded in ‘65, late ‘65, and it came out in ‘66.

LeValley: Okay? And there’s a hit on that first record. “7 and 7 Is.”

Echols: You know, that was on the second one.

LeValley: That was on the second one. Okay.

Echols: The first one had “My Little Red Book”, which was on the radio. It received quite a bit of airplay. I think it went up to number 20 or something. Oh, yeah, so it did pretty decently.

And then the next album, which is called Da Capo, and that had “7 and 7 Is” on it.

LeValley: I didn’t realize you had a hit before “7 and 7 Is.”

LeValley: Well, what was it like hearing your band on the radio?

Echols: It was just amazing, because we’ve been around for a long time. We were signed to a recording contract with Del-Fi Records, and Bob Keane, and we played with The Bobby Fuller 4, and then Glen Campbell, and he was a studio musician on the label as well. So, we had played quite a few sessions with different artists, and so, having a record of our own actually played on the radio was really mind blowing, you know.

LeValley: I’ll bet.

Echols: Yeah, it was really cool.

LeValley: Now you mentioned seeing the Beatles show at the Hollywood Bowl and having all these women screaming, did you guys have groupies? Or was that even a thing yet?

Echols: After we started, we became Love, and we had a charted record. So yeah, we had groupies, and we lived in a castle, and we lived kind of a fairy tale life. Yeah. It was in the Las Feliz area. So, everybody at that time who was anybody was there. An Airplane, Bob Dylan, The Doors, all of them would come and stay there and hang with us. So, it was cool.

LeValley: Okay. Wow.

Echols: Yeah, we.

LeValley: Who did you say would hang with you?

Echols: Let’s see. Jimi Hendrix quite a bit, because we knew Jimi. We recorded with Jimi first. The Doors because we got The Doors their contract with Elektra and Janis Joplin and Grace Slick from the Jefferson Airplane. So, we had quite a menagerie of different groups coming there to see us, and hey, you know?

LeValley: Like hang out with you at the castle.

Echols: Yeah, and stay there because it had, I think, like 60, 70 rooms. It was a huge place, so they would just come there and hang out and party with us whenever they were in town.

LeValley: Amazing.

Echols: Yeah. So, we were living the rock star’s life before. You know. We were kind of the beginning of that scene, you know.

LeValley: Right.

An Airplane, Bob Dylan, The Doors, all of them would come and stay there and hang with us.

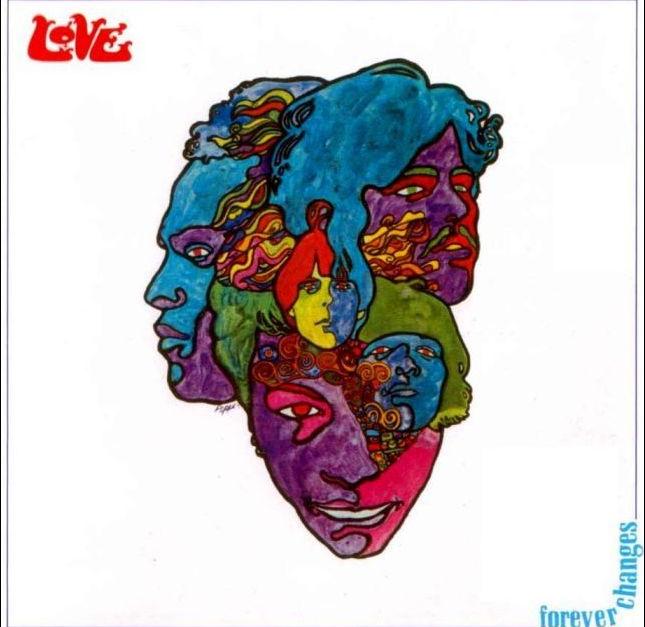

LeValley: Well, Forever Changes didn’t sell well when it came out but, of course, it’s since been hailed as a psychedelic masterpiece. Did you and the band indulge in psychedelic substances around that time?

Echols: Oh, absolutely. Yeah. We took acid. We probably by that time had taken at least a couple 100 doses of LSD, so that was a routine for us, but and so smoking weed was routine. That was what everybody did then, and

Echols: We expected the album to do a lot better than it did. It didn’t receive quite as much promotion as it should have and there was a lot of kind of problems going, you know, as far as recording Forever Changes. But you know, later on, of course, it became kind of an iconic album. And now it’s, you know, considered one of the top records ever recorded.

Echols: And actually, the people in Great Britain and London. The House of Parliament gave us a proclamation that Love Forever Changes was the best rock and roll record in history. So, we still have that proclamation over the Beatles and the Stones and Queen and Led Zeppelin. Love is sitting on top, which is amazing.

LeValley: Yeah, it seems to make just about every critic’s ‘Best of’ list.

LeValley: I first heard it as a sophomore in college. My sophomore roommate played it for me, and it immediately grabbed my attention–like, Wow! That’s pretty unusual, you know.

Yeah, I had never heard of it before, or heard of the band at the time, but it made an immediate impact on me.

Echols: Well, it did a lot of young people growing up during that period because it spoke to the hassles that we were going through– the Civil Rights movement, the college uproar, the Viet Nam war. Everything was, you know, kind of happening at the same time. So the album was kind of…It was basically a newsreel of the times that we lived in so.

LeValley: And there’s that one line in it that goes something like “the news from today will be the movies of tomorrow.”

LeValley: Really prophetic.

Echols: “Turn to blood, and if you don’t think so, go and turn on your tub.” That was a gentleman from that was AWOL from the Viet Nam War, and we were playing with Janis Joplin in a place called the Warehouse in San Francisco, and our dressing room was right near the stage, and Janis was really, really loud. So, we went around where the bar was now back. Then the young people under 18 could be in the same place where alcohol was served as long as they were in a partitioned area. So we went to the area because we were, at that time I think I was 17 or something, and so we were sitting there, and this guy comes and plops a big gun. I don’t know what the hell it was, but I know it’s a huge gun on the table. And so, “I want you guys to listen to me.” I said, “Sure, hey.” Of course we’re going to listen to him, and so he proceeds to tell us how blood mixed with mud turns to gray and that when one of the wounded servicemen were would be in the mud, screaming out for his name, or for God’s name rather, or his mom or somebody, and then one of the lines in the song is “You can call my name. I hear you calling my name.” So he’s basically calling out for God. Well, that was all of the things that the gentleman from Viet Nam had told us. And so Arthur put all of that. Arthur was always doing that he was writing down because he was. Basically, he wasn’t much of a musician, but he was a hell of a lyricist and a wordsmith, so he could just, you know, find just the most mundane things and find something profound in it. So, he really was a fascinating poet.

LeValley: Were you surprised by how much Forever Changes grew in stature over time?

Echols: Oh, absolutely. I’m still shocked now. We play places like we played a couple of years ago in Sefton Park and Liverpool, and over 90,000 people showed up, and they showed up in the rain to hear us play, and they’re singing along with us at Sefton Park. That would have been right after the Covid thing, so I think it would have been 2019. I believe.

LeValley: So then this was a band fronted by you?

Echols: Oh, yeah, we’re still, we’re Love with Johnny Echols. So no. Arthur passed away in in 2006. So yeah, we’ve been traveling and playing and touring as Love since then. So.

LeValley: Wow! I didn’t realize you were drawing crowds that big.

Echols: Yeah, we fill out. Most of this we sell out, and we played Shepherd’s Bush last year, and we filled it up. And that’s where the Stones and Led Zeppelin and all those groups. So we got to put our names there on the wall with all the other guys that played there. And yeah, we sold it out twice. Yeah, we’re fortunate.

LeValley: When did it seem to really take off? I mean, you know, it was like commercial bomb at first, and then like, when did it start? When did you notice that it was like really starting to pick up in terms of critical claim?

Echols: Well, that would have been around 2001. Arthur had gone to prison. He had a gun charge, and he had got sentenced on a bogus gun charge, and he was sent to prison for 12 years, and he spent six years, and when he got out, the group, I wasn’t with that initial group when he first got out, because I had obligations elsewhere. But he started touring, and we played, let’s see, Albert Hall, or the Albert Hall in the there was another hall in there. I’m not remembering the name of it, anyway. Sold it out in England, and he was playing to the Isle of Wight, and several sold out concerts, you know, all over England and Europe, and because people, you know, realized that he’d gotten a raw deal. Yes, but they wanted to see the group that they’d heard so much about. So, we were able to, or he was able to at that point to sell out all these venues, and then I joined them, and we played until he died.

LeValley: Yeah.

Echols: And it’s the same group we’re playing with the gentlemen now that have been playing with us since 1994. So they’ve been playing this music longer than the original members had been alive at the time we did it. So, they do this music perfectly, and when you come to one of the gigs. If you close your eyes you won’t know you’re not listening to the same group that did all those records.

Many times we would be booked to play somewhere and we get there, and they realized that we were a racially mixed group, and they would just cancel the concert.

LeValley: Well, Love was one of the first racially integrated bands at the time. Did that affect how you were perceived by, like, labels, venues, or fans?

Echols: It was a negative because we were right during the Civil Rights movement, and people had, dogs sicked upon them, and fire hoses just for trying to vote.

Echols: you know. So imagine these same people trying to go to a club and hang out together, or dances, or whatever. They didn’t want any part of us, because, you know, if a group was like an all black group, they could play at the R & B clubs and all white groups would play at clubs that catered to white people, but they did not appreciate race mixing back then. It is what they called it, and so many times we would be booked to play somewhere and we get there, and they realized that we were a racially mixed group, and they would just cancel the concert.

LeValley: Oh, man!

Echols: That happened to us quite often. So that’s why Love didn’t do at that particular time as well as the other groups like The Doors, who, as I mentioned, we got their contract for them, their record deal. So, they were doing quite well, and Love should have, and would have, had we not been a group that couldn’t like, we couldn’t play in the South and most of Middle America. We couldn’t play so we could play on the East Coast and parts of the Midwest, like we could play in Detroit and Chicago, and places like that, and on the West Coast from Portland, Oregon and Washington and all of California we were able to play. So we were able to make a living that way. But we weren’t able to break out the way The Doors and and Iron Butterfly and other groups did, because of the facts that we were a racially mixed group.

LeValley: Yeah, I was gonna ask you a little bit about that. Did you feel like you were part of the Sunset Strip scene alongside bands, with like the Byrds and The Doors?

Echols: Well, we were the Sunset. There was Love at the top, and then below that there would have been The Byrds and The Doors and The Leaves and Iron Butterfly and Buffalo Springfield. But no, at that time Love was probably able to outdraw the other groups that I mentioned many, many times over, so we could fill up the Hollywood bowl or fill up Earl Ward showgrounds in Santa Barbara, which was a very, very large venue, so we drew larger crowds than the other groups I mentioned, even though they had more hit records than we did for some reason, and to this day I don’t understand why, but we were taken to the hearts by the people in Los Angeles and Hollywood, California area, and our gigs wherever we played, was considered an event, and so it would always sell out.

LeValley: Wow!

Echols: Yeah.

LeValley: Well, I heard something about you having a bunch of songs that you’d written that Love was going to record, but then never did.

Echols: When we were doing Forever Changes. It was meant to be a double album, so Bryan had worked on one side of an album, and I had worked on one, and Arthur would get the two sides, which became Forever Changes. But when we get to the studio the Record Company kind of reneged on the agreements that we had to do a double album, and said, ‘We’ll do the 1st album, and then we do another one soon after this one, because doing a double album is way more expensive, you know, than doing a single album. Even two single albums are less expensive than one double album, because you know the packaging, and all of that, it causes it to be quite a bit more expensive. So anyway, they didn’t. And there was a lot of turmoil happening around the fact that, you know, we felt basically betrayed by our record company. So, it took a lot to record Forever Changes that there was a lot of false starts and ups and downs with it because of the fact that our hearts just weren’t in it until we had a meeting and decided that, you know, we probably weren’t going to play together anymore. So if we’re going to go out, we should go out with a bang, and so we did the very best we could on Forever Changes the record that was actually released. And lately some of the songs that didn’t make it were also re-released on box sets and things–like they’re doing another one right now where they’re going to release Forever Changes again, and the box set. But all four of the first Love albums, the Love album Da Capo, Forever Changes, and Four Sail, they’re also going to re-release.

LeValley: Okay, I read that you and bassist Ken Forssi, who was your roommate, developed an addiction to heroin.

Echols: But the donut stuff is total bullshit. No, we were stopped, you know, we’re waiting for our connections, the drug man to show up and we were in front of a diner or something like that. And we’ve been sitting there for hours, because when you’re addicted to drugs, when the guy tells you to wait, you wait. There were no cell phones, or, you know, answering stuff, answering machines or anything. So if he says, I’ll meet you on this corner at this particular time. You’ll wait. He has all the power. And the two of us were on this, waiting in a very expensive sports car. Kenny had a Jaguar XKE at the time, and the two of us to interracial again, because even in California race mixing sometimes was frowned on. If they saw a black guy and a white guy together, they felt that we were up to no good, and during that particular instance, we were up to no good. We were waiting to connect.

Echols: And so the gentleman that owned the diner came out and asked us if he could help us, and said, no, we don’t need your help, he said. Why are you sitting in front of my place? I said, ‘We didn’t even realize your place was here. We’re just waiting to meet someone’, and so we stayed there probably another hour, and police come, and they, you know, have us get out of the car, and they chat with us for a while, and they realize that, you know, we haven’t done anything wrong. So they leave.

Echols: Someone somewhere had seen us being, you know, outside the car being questioned by the police, and so they said we must have been involved in some kind of robbery or something. So it started from there, and rumors go that.

Echols: You know, at that time, we are pretty well off financially, so there would have been no reason on this earth for us to be robbing anything, even though we were drug addicts. The fact was, we were making quite a lot of money, so that was not something that was necessary for us to do.

Echols: If we would have done it. In the first place, which is highly unlikely. I don’t think I could have ever gotten that fucking high that I would do something like that. But anyway, that rumor, just, you know, went around and a couple of magazines. I think Zigzag was out of business now, because they were sued, for all they had to do was their due diligence. Go down to the Hall of Records and find out whether or not the two of us had been arrested, which we weren’t. And so, anyway, yeah, that’s just another one, and then there were other ones that we were Communists, and we were part of the CIA because of “My Little Red Book” that we were part of chairman Mao, you know. And this stuff. So yeah.

LeValley: It wasn’t even written by you guys.

Echols: Yeah, no, that was written by Burt Bacharach, but because the title of the song was “My Little Red Book” then we, of course, were Communists. And so, anyway, that’s just part of music. If we didn’t give that many interviews, and when you don’t talk to people and give interviews, they kind of make up their own stories, and that’s what they did.

LeValley: Well, how did you recover from the heroin addiction?

Echols: Well, it was probably serendipity again. I was in New York. I decided I couldn’t–because I was so close to so many people here. I couldn’t get away from the drugs unless I left, and so I moved to New York and late night on the TV there would be a sign off, and usually a Catholic priest would come on, and he’d give a benediction and talk about some of the verses in the Bible or whatever, and that would be the sign off of the station. And so, I was sitting there late at night watching. I was in a hotel and the priest came on. And he said, if someone is hurting and addicted to drugs, and they’re interested in turning their lives around, call this number. And so I thought, what the hell. I called the number, and the priest answered, and he said that there was a bed open, because some, for some reason, the person that was assigned to it, decided not to come, and if you want, you can go to Bernstein Institute, which was a rehab center in New York, and I called the number, he said, ‘Well, if you can get over there within the next hour, there’s a place for you’, which I did, and I stayed there for 90 days, and I was able to clean up, and I’ve never used illegal substances again.

Echols: So that was serendipity, or the universe, or whatever. Who knows, but you know, it was just happenstance that I was watching that station that time, and actually picked up the phone and called.

LeValley: Did that have an influence on you in terms of like becoming a Catholic, or anything like that?

Echols: No, actually, no, I’m still pretty much an agnostic, you know. I don’t know what I don’t know, so I have to leave it that way. I’m not an atheist, but I just don’t know. So, no, that didn’t… it could have been anybody. It just happened to be a Catholic priest, giving, you know, the benediction at the end of the day, so I thought about it a lot of times, and wondered how my life would have been had I not been there watching TV at that particular moment, you know.

LeValley: Yeah.

LeValley: Well, my understanding is that after the commercial failure of Forever Changes, Bryan Mclean left the band to start a solo career and that Lee fired you, Forssi, and the drummer, Michael Stewart. Is that accurate?

Echols: That didn’t happen. What happened was after Forever Changes, Brian had worked out a deal with Electra Records to do a solo album. He was still going to be with us with Love, but he was going to do a solo album, and that was one of the stipulations which none of us actually knew that, unbeknownst to us, when we were having problems during the recording of Forever Changes, they had worked out a deal with Bryan to do that.

Echols: and Bryan calls me up and says, ‘I’ve just got to deal with Electro Records, and we’re gonna do a solo. Would you like to play on my album?

Echols: And I said, ‘Sure, I’ll play on your album. Let’s go break the news to Arthur’. So we went over to Arthur’s house and told him what had happened, and he said, “Wow, Bryan, that’s fantastic. You’re fired.

Echols: He didn’t really have the right to fire Bryan at the time, because we were all equal partners in the group, but he did so, and he changed his mind later. But Bryan was, you know, so taken aback by him actually doing that, that he refused to come back and play. So, we played a few gigs that we played in Santa Monica Civic auditorium and a couple of others, but without Bryan.

Echols: And it just wasn’t the same. It didn’t sound the same. The feeling on stage wasn’t the same. So, we decided to go our own way. And so that’s what we did. Arthur didn’t have the power to fire anybody. As I said, we’re all signed and we all had equal shares in the name Love. So, you know, unless we wanted to go, there’s no way he could fire anyone.

LeValley: Did it bother you that he continued, to use the moniker Love with other musicians?

Echols: At first it bothered us, but then we it was helping to sell records. And so, the royalties we’re getting, because Arthur’s out there playing all the time.

Echols: Things were changing, you know. Jimi Hendrix kind of helped bring in the things so that the psychedelic music that black people were playing, and so we were able to play clubs that normally would have been R & B clubs, but because of Jimi Hendrix, some of the black clubs were now playing that type of music–psychedelic music. So, there was quite a lot more work.

Echols: You know, and so Arthur’s playing these clubs and the records are selling, and so he tries so many times to get us back together. But it just wasn’t meant to be.

Echols: And as I mentioned, he ended up going to prison. Well, right before that, they released a box set. Rhino records did. And we were going to go on tour, and they’d offered us really a huge sum of money to, you know, to go on a world tour. So we were back in SRI doing rehearsals and getting ready to do it, and then Arthur gets arrested for brandishing a firearm, and he gets 12 years.

Echols: We played a few, you know, Bryan and me and Kenny and and Michael played a few times together, and this definitely wasn’t the same again. And so we all went our separate ways and play together once in a while, but Love never. All of us never got on stage and played together again.

LeValley: Well, you did reunite with Arthur Lee in the early 2000s for some well received shows.

Echols: Yes.

LeValley: Yeah. What was that like?

Echols: Well, we toured England and Europe. We were because, you know, Arthur had gotten out of prison and gotten together with the guys that we play with now.

Echols: we were able to rebuild the audience and the fan base. So, we were selling out, you know, very large venues, which, as I said, we still do now. So, we were getting a younger audience and, you know, many of the older people that initially came to see us play were still coming. But as of now, probably 90 or more percent of the people that come to see us are much, much younger, you know. So, most of the people from our age group are long gone, so there’s a few stragglers and few that are left, but it’s very few left now. So our audiences were not alive at the time we recorded these records, but they’ve taken it to heart and Forever Changes has become iconic, and we’re doing very well, we’ll be going again. We just finished a US tour what we played.

Echols: I think it was 30 States we played in in a matter of a couple of months, and we’re going on another world tour which will start next spring in April, and they’re re-releasing all of the Love albums on vinyl. So, we will be touring in support of that. So, we’ve got a full work schedule ahead of us.

LeValley: Okay. What’s something about Arthur Lee that his fans wouldn’t know about?

Echols: Well, that Arthur really was not a musician. I think most people thought of Arthur as being, you know, because he’s writing, or his name was on the songs as writer, and they’re considering him as this great musician that played. Arthur never played except for harmonica on a song called “Message to Pretty”.

Echols: He didn’t play on any of our albums.

LeValley: Wow! I didn’t realize that.

Echols: Yeah.

LeValley: Huh!

Echols: Yeah. People, you know, have this assumption that because they see Arthur’s name, and he’s standing out front, or whatever that he played on them. But no, he didn’t. I think he played on “Revelation”, too. He played harmonica. So there’s a couple of songs that he played harmonica on. But that was it.

LeValley: So what did he do on the Bryan McLean songs? If he…

Echols: Nothing.

LeValley: He didn’t participate?

Echols: He would. Sometimes he would do vocals with Bryan on “Orange Skies”. Bryan wrote. Arthur did the vocals on that on “Alone Again Or”, which is probably the most well-known of our songs, because it’s been covered so many times, and Arthur did vocals with him. So, on Brian’s songs, Arthur would would sometimes do a joining vocal or a background vocal.

LeValley: Well, as we mentioned, you’re performing love’s songs with the group called Love with Johnny Echols.

Echols: Correct.

LeValley: Are you doing any new material, or is it strictly an homage to the original catalog?

Echols: Most of the songs that we do, because that’s what the people want to hear is the older catalog. But we have done a couple of new songs, and we will be re-releasing some songs that we had started, and that were never finished with Arthur. And so that will be released sometime next spring as well, so we will have several new songs. They’re new old songs.

LeValley: Did you ever record any of those songs that you had written for Love back in the mid to late sixties?

Echols: Yeah, there are some demos that I worked on, and some stuff that that I did with the group. But there are–I think we’ve done like 6 or 7 songs with this particular lineup, and that we’re still working on finishing so hopefully when they’re releasing all of the other ones. We’ll release those at the same time, because then we can tour for all of them at the same time.

Echols: So we’re looking forward to that. Anyway, we’ll see how it goes. But that’s the plan as of now.

LeValley: Okay, well, I’d like to wrap this up. Is there anything that you wanna say before we go?

Echols: Well, I thank everyone for continuing to support us, because it’s just mind boggling to me at this age to be playing this music and traveling and working so much and still remaining relevant. So, it’s amazing to me. It’s like some kind of fairy tale that I’m living in. But, you know, it’s amazing to me. And I’m, you know, thankful and grateful that people are still listening to our music.

LeValley: Alright! Well, great.

LeValley: Johnny, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today.

Echols: It’s been my pleasure.

LeValley: I also want to thank Pamela Des Barres, who helped facilitate this meeting.

Echols: Yeah, I love Pamela. She’s a sweetheart.

LeValley: Yeah, she seems really nice.

Echols: Yeah.

LeValley: All right. Well, thank you so much. Have a wonderful day.

Echols: Thank you. You too. Alright, bye, bye, take care.

Gallery

Recent Articles

Unicorn by Rio Kosta–Album Review

•

February 24, 2026

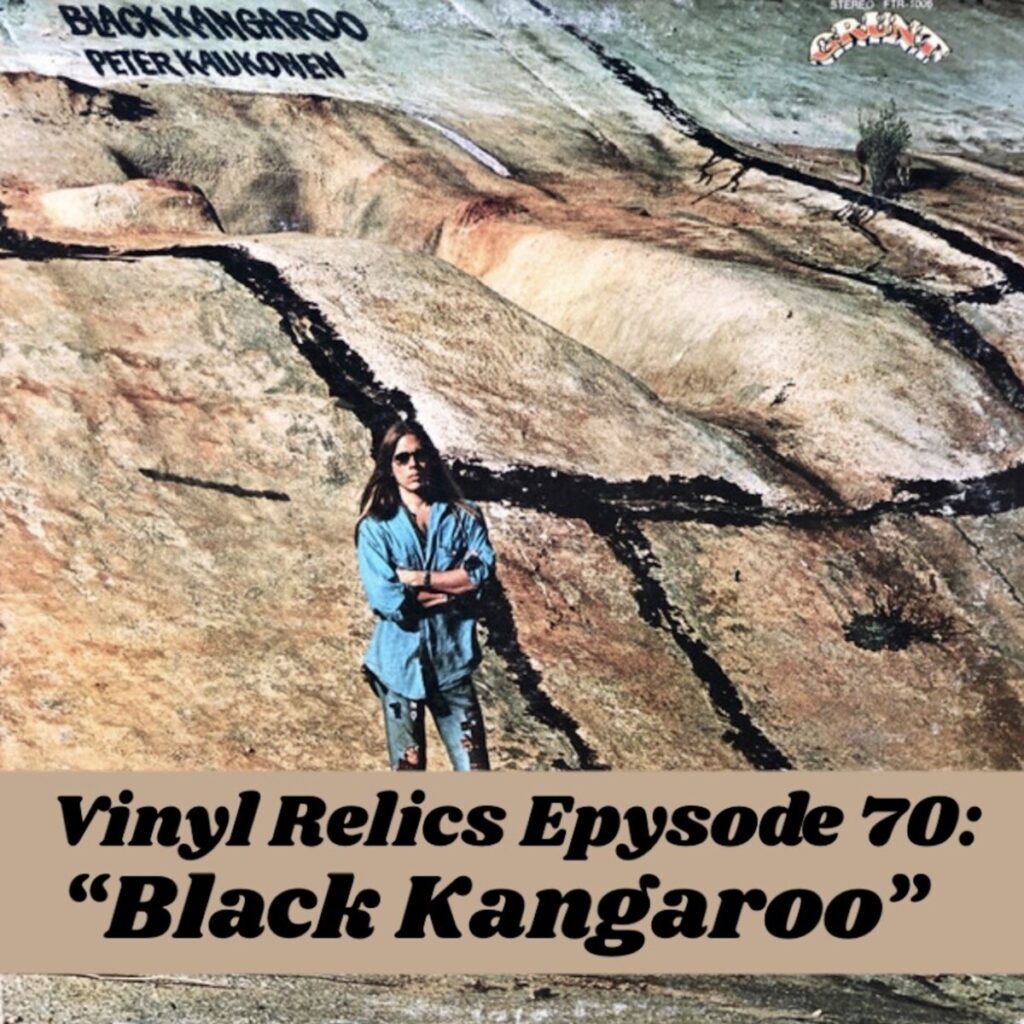

Vinyl Relics: Black Kangaroo by Peter Kaukonen

•

February 21, 2026

Loading...