Psychotropic Cinema: Beyond the Black Rainbow

Psychotropic Cinema: Beyond the Black Rainbow

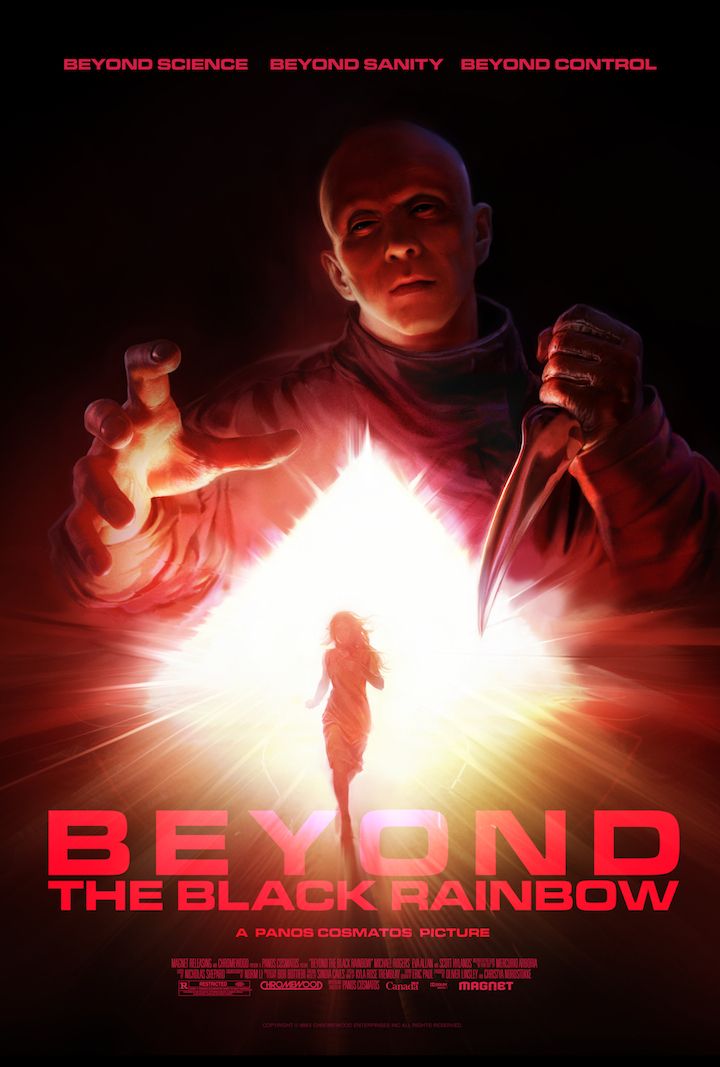

The 2010 film Beyond the Black Rainbow is the fantastical feature film debut of Canadian writer-director Panos Cosmatos. His father was an accomplished director in his own right, which gave Panos the knowledge of how cinema can be made. Not that he would ever make the kind of brash Hollywood movies his dad George directed (Rambo, Cobra), but luckily George Cosmatos’ success was able to fund this first outing for Panos (the residuals from Tombstone funded the bulk of the film).

The plot centers around the good-intentioned Arboria Institute, a research facility established in the Sixties, and dedicated to the union of science and spirituality. The institute is a research facility working with neuropsychological drugs, sensory

The psychedelic rangers amongst us are taught that the inward journey is paramount, but this film ponders that validity.

therapy, and “energy sculpting.” Unfortunately, the founder’s successor was corrupted by a far-reaching and inexplicable psychedelic experiment. This movie is ultimately a sci-fi horror film about new-age psychic research gone wrong.

The year is 1983. The setting outside the institute is an utterly bland world of wood-paneled browns and beiges, but the Cold War threat of nuclear annihilation is always on the back burner. Conversely, the majority of the film takes place within the walls of the Arboria Institute, its futuristic and cold design informed by science fiction past (THX 1138, 2001, The Andromeda Strain). On reflection of the movie’s 1980s time period, Cosmatos has said, “The time had a very vivid feeling: mostly a blend of being hypnotized and intoxicated by pop culture and an omnipresent terror of the world coming to an abrupt, apocalyptic end…The movie takes place in a nostalgic landscape that is poisoned by fear and regret.”

Barry Nyle was the protégé of the institute’s founder Dr. Mercurio Arboria. He was the subject of the aforementioned experiment, which is only shown in a brief, stark flashback from 1966. Barry is dosed with an eyedropper on the tongue (LSD or something more powerful?) before descending into a mysterious oily black pit. While submerged, he becomes a multicolored waxen figure, contrasting greatly with the wholly black-and-white scene to signify the psychedelic experience. He emerges from the blackness, vomiting the viscous liquid out, in a calmly deranged state. This intense event leads him to murderous madness (there is an Altered States filmic parallel here, even musically).

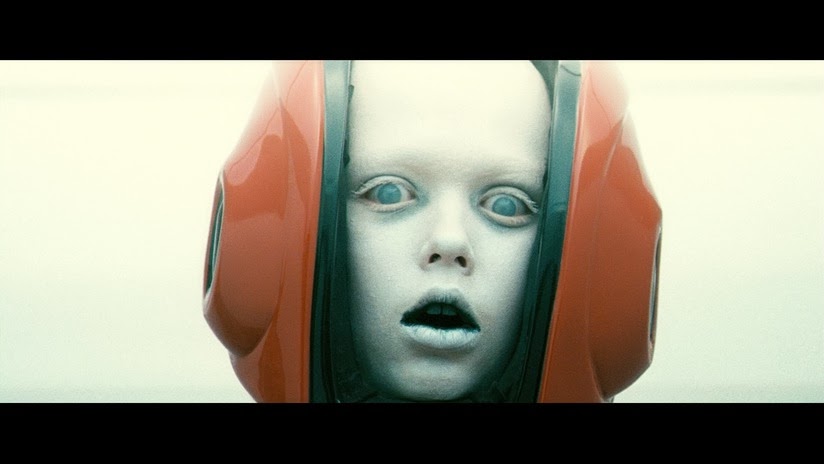

Thematically, Beyond the Black Rainbow is ultimately about control. The control of human captivity as well as the inner control of one’s self. In the present day 1983 of the story, Nyle keeps a young woman captive in the institute. This woman, Elena, possesses extraordinary psychic powers that can only be subdued via a glowing and pulsating pyramid. She is docile and mute–her spirit is sad and broken, and she only communicates telepathically. She has spent her entire life in captivity. The control Nyle exerts over Elena is out of need and want. She needs to be controlled because her telekinetic powers are astounding and highly dangerous. But his wanton needs create a sexual tension that directs his every decision. He leads her to believe that she is sick and requires his help. As he plays the god of her world, he becomes deranged with power and ultimately succumbs to the insanity he’s held at bay for the past 17 years.

The throbbing vintage synth soundtrack by Black Mountain keyboardist Jeremy Schmidt (aka Sinoia Caves) is almost a character on its own. The prog-tinged synth-wave sounds echoing throughout the entire institute are informed by his retrofuturist work. Schmidt’s style sits squarely between John Carpenter’s minimalist early work (Halloween, Escape From New York) and a more modern composer like Cliff Martinez (Neon Demon, Only God Forgives).

Stylistically, the movie is a futuristic funhouse of figments, a mod palette of bold primary colors. The glowing red tinge of menace overwhelms the bulk of the facility but especially projects the danger of Nyle’s interactions with Elena. Elena’s room is blue to elicit calm. She is placated and controlled. Elena is a subject but also a prisoner.

The cinematography by Norm Li is innovative, frugal, and painstakingly deliberate. Shot on 35mm film, the movie was initially thought by some to be too expensive a medium for this low-budget flick. Li found a way to accomplish the look that Cosmatos wanted to see with thoughtfulness and careful planning by utilizing a specialized Panaflex camera that significantly cut the cost of using film. The claustrophobia of the tight interior spaces, coupled with the camera framing, sets the mood of hopelessness and confinement. The 1966 flashback scene is an almost direct stylistic copy of 1989’s The Begotten, a stark, high-contrast black-and-white scene that took some effort to accomplish and is strikingly beautiful in its design.

Without giving too much of the surprising plot details away, many of the characters wind up dead, with only one survivor. The ending leaves the viewer wondering if the inward journey is truly more enlightening than the outer realms of nature itself. The psychedelic rangers amongst us are taught that the inward journey is paramount, but this film ponders that validity. If one has never seen the outside world, does the outward experience not seem more beatific?

Cosmatos claims he wasn’t allowed to watch R-rated films in his youth. When he went to the video store, he would look at the VHS cover art and imagine what the movie might be like. This unknowing and imagined dreamworld of sci-fi and horror informed his formative years. Because of this background of envisioning plots based on production stills and cover art, watching this flick is like staring into a rippling watery reflection. It is acted and filmed like a hazy memory of something that may or may not have happened.

Is Panos the new Jodorowsky (The Holy Mountain, El Topo)? He was certainly hip to the midnight movie king’s psychedelic films, and Cosmatos was definitely drawn to Lucas’ THX 1138 future dystopian style. The plot of Beyond the Black Rainbow knowingly shares a kernel of storyline with David Cronenberg’s Stereo (1969). According to Cosmatos, Beyond the Black Rainbow was visually birthed from Saul Bass’ 1974 film Phase IV, and the production design also indicates a deep affection for Michael Mann’s mid-eighties films (The Keep, Manhunter).

The story idea for Beyond the Black Rainbow, as originally written by Panos, was very detailed, but he stripped away layers to reveal a threadbare plot comprised of hints and suggestions. This style is akin to the “cut up” methodology that William Burroughs used in novels such as Naked Lunch and The Soft Machine. By trimming out parts of the plot and revealing what lies beneath, new divinations are revealed. This adjustment makes the storyline more dreamlike and abstract, where the viewer is just as much in the dark as most of the characters in the film. It creates a mood of abstraction–an idea of what things should be but not necessarily what they are–a dream world. Was it dreamt, or was it real?

Beyond the Black Rainbow–Wikipedia page

Gallery

Recent Articles

Loading...