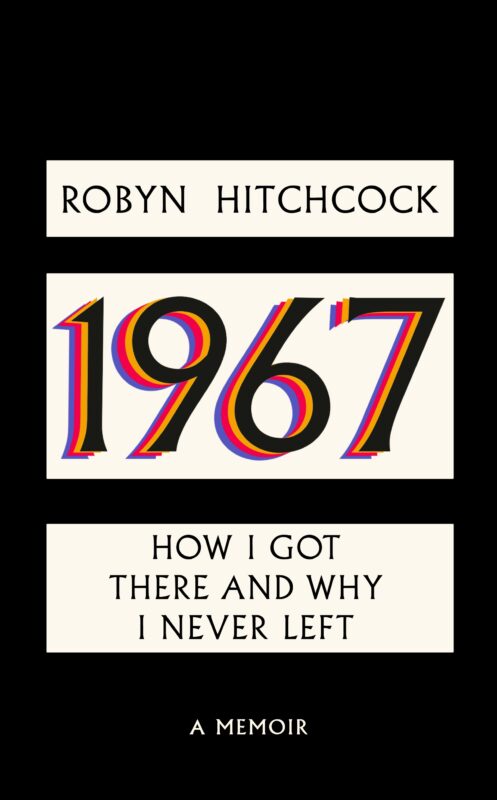

1967: How I Got There and Why I Never Left by Robyn Hitchcock–Book Review

1967: How I Got There and Why I Never Left by Robyn Hitchcock–Book Review

The notion of a musical artist penning a memoir is not new or groundbreaking. Autobiographies that relive the childhood exploits that led to Eric Clapton, John Lennon and countless others usually fall into the same rags to riches template: humble upbringing, small and squalid living quarters, sometimes abusive parents or relatives, a war or other monstrous interruptions that invariably lead to the requisite musical fame and glory. Many are too long – some are too short on the juicy details.

Known for his early musical work with The Soft Boys and later with various ensembles including The Egyptians, Robyn Hitchcock’s thoroughly enjoyable 1967 is a breath of fresh air in its marked contrast to said autobiographical pattern. Robyn grew up in a loving, artistic. and comfortable multi-generational home and went to private school called Winchester College. It was his first year at Winchester that comprised (mostly) the entirety of 1967.

“One of the main functions of private education in Britain is to stunt people emotionally and then send them out to run the country.”

Where most rock memoirs cover the author’s life up to or just after the point they found fame, Hitchcock’s memoir covers a singular (but formative) year and only that year. 1967 (the year) as we now know was the peak of psychedelia and psychedelic music within most definitions. To be a shy twelve-year-old on the verge of finding one’s own personality in such a momentous year must have been exhilarating to say the least.

Hitchcock highlights his first year at Winchester based around his newfound awareness of popular music. While he learned about Jimi Hendrix and the Beatles at home with his sisters by way of the de rigueur portable transistor radio, it was the publicly accessible record player (“gramophone”) at Winchester that led to his most significant discovery to date: Bob Dylan. 1967 traces important releases including “Highway 61 Revisited,” “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” and various singles by Spencer Davis and the Rolling Stones.

“Nineteen sixty-seven finished, but it never ended.”

1967 is less a tell-all that relates to a long childhood and more of a snapshot of an important time. An essential snapshot in time of a nascent psychedelic music fan who goes on to create his own style. When you learn at the end of the book that Hitchcock wrote the majority of it on an iPhone during the hours from midnight to 6:00 AM due to insomnia, you gain an even greater appreciation of his dedication to his craft.

C. Elliott Photography

“Between the groovers and the meatheads lie the semi-groovers. Semi-groovers are literate boys with good taste who nonetheless have some conventional tendencies: they’re not planning to grow their hair down to their navels or smoke themselves into a hashish coma when they leave—and they may even wear ties in their free time.”

“Between the groovers and the meatheads lie the semi-groovers. Semi-groovers are literate boys with good taste who nonetheless have some conventional tendencies: they’re not planning to grow their hair down to their navels or smoke themselves into a hashish coma when they leave—and they may even wear ties in their free time.”

Lacking the over-wrought trope of pasty white young Englishmen “discovering” American blues, 1967 focuses on the organic social growth and musical discoveries of a very kind and considerate young boy in the UK in 1967. Robyn Hitchcock is an erudite writer with a talented pen (finger) and a way with words. The artful turns of phrase we have become accustomed to in his songs like “Balloon Man” or “Madonna of the Wasps” originated in Winchester College. How does it feel indeed?

Gallery

Recent Articles

Loading...

Vinyl Relics: Would You Believe with Billy Nicholls

- Farmer John

A Tale of Crescendo ~ Chapter 9: The Clash; Chapter 10: The Reckoning

- Bill Kurzenberger