Interview: Peppy Castro of The Blues Magoos

Interview: Peppy Castro of The Blues Magoos

Jason LeValley of Psychedelic Scene:

This is Jason LeValley. I’m here with Peppy Castro from the Blues Magoos. Thank you for being here, Peppy.

Castro:

My pleasure, Jason. My pleasure. I’m happy to be anywhere at my age. It’s the George Byrne routine.

LeValley:

You were in a band called the Blues Magoos, of course. The name implies that you were a blues band, but you weren’t really a blues band. You were more of a psychedelic rock band. How did you get the name?

Castro:

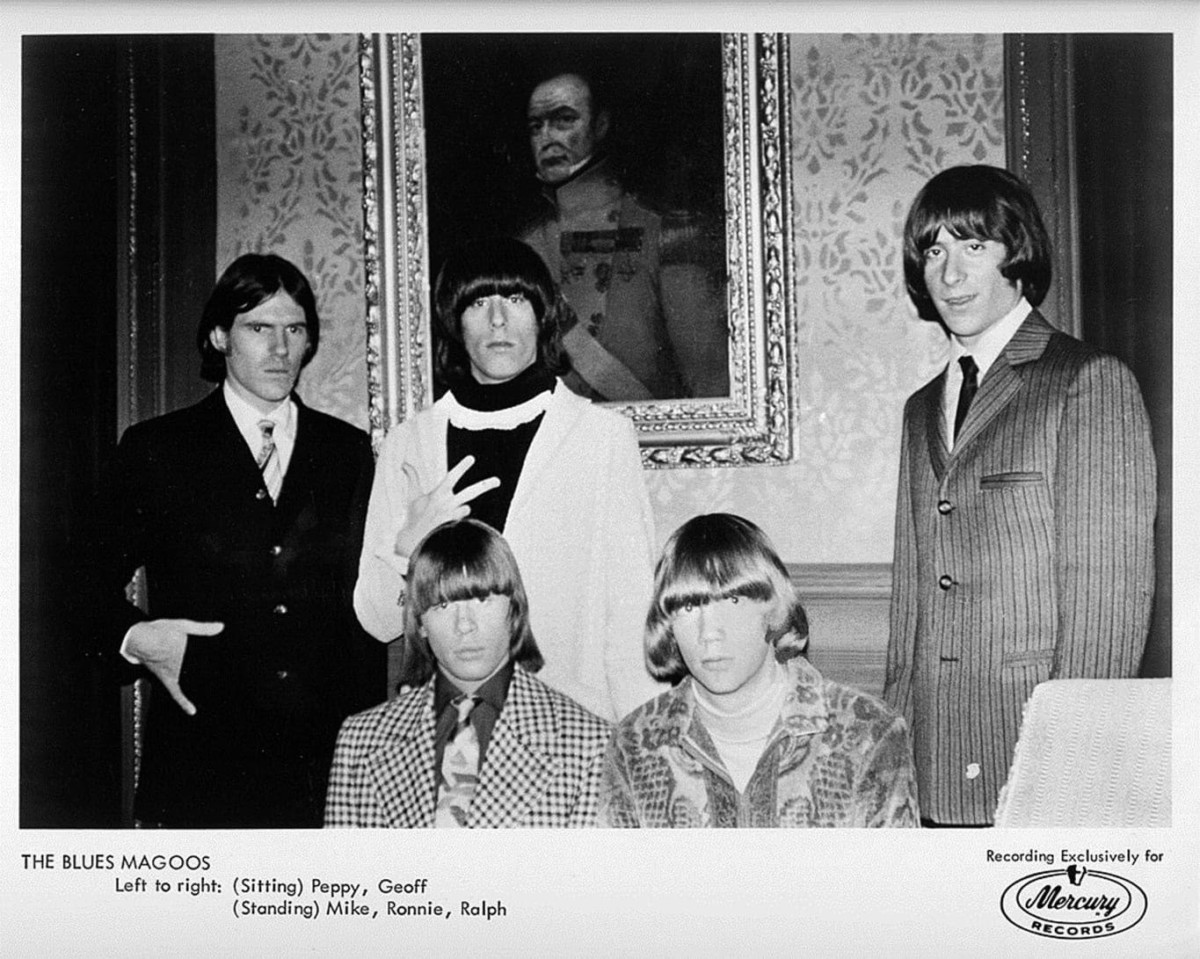

Well, the name, broadly, well, we were three guys from the Bronx, basically. I grew up in Manhattan, and my dad passed away when I was five months old. I was born Emilio Castro. And what happened was Castro died when I was five months old. My mother remarried when I was four. We migrated up to the Bronx. I got adopted to a guy named Thielhelm. And then they dropped Emilio to Emil. So I became Emil Thielhelm. So let me run that out of the way right now before I get back to the Magoo name. And so we were The Trenchoats originally. And then we started migrating down to the Village because that was the only place where it was safe to go. Because when you were in the first wave of New York bands, growing your hair and wearing boots, you were taking your life into your hands if you were anywhere around New York other than the Village. We migrated down there. We worked up through all the clubs, and we ended up having a steady gig at a place called the Night Out Cafe. We were approached by two industry veteran guys who were producers, and they actually chewed over the stuff when they were trying to sign us to an independent production deal.

Castro:

They came up with the name with some people originally, I believe, from CBS. The Blues Magoos, actually, we did not come up with the name ourselves, but because our persona was so street and like, these guys are funny-looking. I think somebody had a laugh at our expense and figured, well, they’re doing Magoos, but they’re also like, wacko young guys with kinky hair and everything else. They came up with the Blues Magoos, which was originally spelled B-L-O-O-S. Then after a few months of doing that, we changed it to B-L-U-E-S. But we do not take the credit for coming up with the name.

LeValley:

Okay. It sounds like the fact that it has the word blues in it was just incidental, almost.

Castro:

Well, I was fortunate enough to grow up in the Village when the Village was going from folk to electric, if you can imagine, because at that point in time, when I’m 14 and 15 years old, because I left home at 14, I’m running around the Village there, and all the coffee houses have guys like Dave Van Ronk and Freddie Neil. Tim Hardin was starting to come up, and Robert Zimmerman is walking around with his guitar case. Richie Havens is walking around as a little

When you were in the first wave of New York bands, growing your hair and wearing boots, you were taking your life into your hands if you were anywhere around New York other than the Village.

troubadour, and all of a sudden, bands like the Lovin’ Spoonful and the Blues Magoos and a handful of other acts that, unfortunately, never went on to great notoriety, were coming up. And so all the clubs were changing over from folk to electric. The blues and good time rock and roll was all around the Village. We gravitated towards some blues songs, and we were very impressed with the first wave of British bands that were coming into the United States,–The Animals being one of them, which had a blues effect on me. But we were also, because we were indoctrinated into the Village, we were listening to a lot of blues artists that the English guys were picking up on American blues, Black blues from America, and then they were putting it in their blender, and they were coming up with all this other stuff, too.

Castro:

So the blues was there. Folk stuff was there. Good time rock and roll was there. “I ain’t going to work on Maggie’s Farm no more”. We’d be playing this stuff before even Dylan was making a record with it. It was part of the culture, actually. But we were also getting high, and we were in the first wave of American bands on the East Coast that were morphing that garage band, psychedelia thing going on.

LeValley:

Yeah. I mean, you guys were from the Bronx, and it seems like the whole psychedelic summer of love thing was more of a West Coast thing. Did it feel… Was it weird being in the Bronx with all this going on around the country and the world?

Castro:

Was there what?

LeValley:

How did it feel being in the Bronx during the Summer of Love?

Castro:

Well, you see, we weren’t really in the Bronx during the Summer of Love. We were out gigging, all over the world. As a matter of fact, I only found out last year that the Blues Magoos played the first rock festival in the United States. We were actually out in San Francisco, and this was a week before the big one, which everybody thinks is the first one. But the first rock festival in the United States was actually in San Francisco, and it was called Magic Mountain or something like that. I have a flyer to it. I’ll send it to you. You’ll be amazed at all the amount of the acts that were on it. Really, even though, yes, I’m in total agreement with you, the musical bubbling up of the psychedelic genre really percolated more in the West Coast, but the East Coast was more indoors. It wasn’t really out because, like I said, I found myself in rooms with Timothy Leary and all these people dropping acid and doing all this stuff on the East Coast. But the scene was not as urban. It was cultivated more in the little clubs in Manhattan, whereas LA and San Francisco was an outdoor environment.

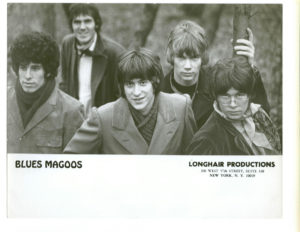

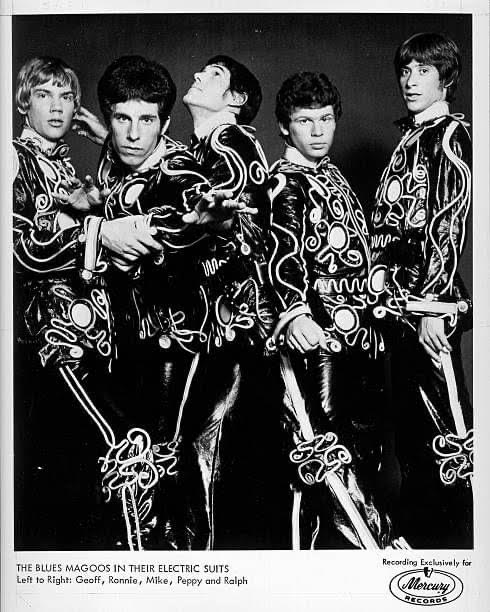

Courtesy of Peppy Castro

Castro:

So that stuff was going on. What was happening in New York is that the first wave of British bands were coming in and starting to do Ed Sullivan. The only thing they wanted to do was to go down to the Village and see what was going on in New York. That’s what was going on in New York at that time, to where we were friending all these other different bands. The Stones were coming in, the Animals, Gerry and the Pacemakers, the Kinks, all this stuff. And the future groupies of New York, would go up to all the hotels. The girls that would hang out in the Village would run up to the Hilton Hotel when they saw an English band was coming in, and then they’d drag them down to the Village and things like that. It was a different percolation going on. And yes, the West Coast gets the kudos of really being more the birth of the scene, but it wasn’t that it wasn’t happening in New York. It just wasn’t as exploited, and it was more indoors as opposed to outdoors. Yet the first festival in the United States, the Blues Magoos were on there with The Grass Roots and Hugh Maskela, and an amazing amount of acts, and that this was the week before Altamont, I believe.

LeValley:

Well, Altamont was 1969, wasn’t it?

Castro:

No, I think it’s before that. I think it’s called… It was from a radio station in San Francisco, and I believe it was called Magic Mountain.

LeValley:

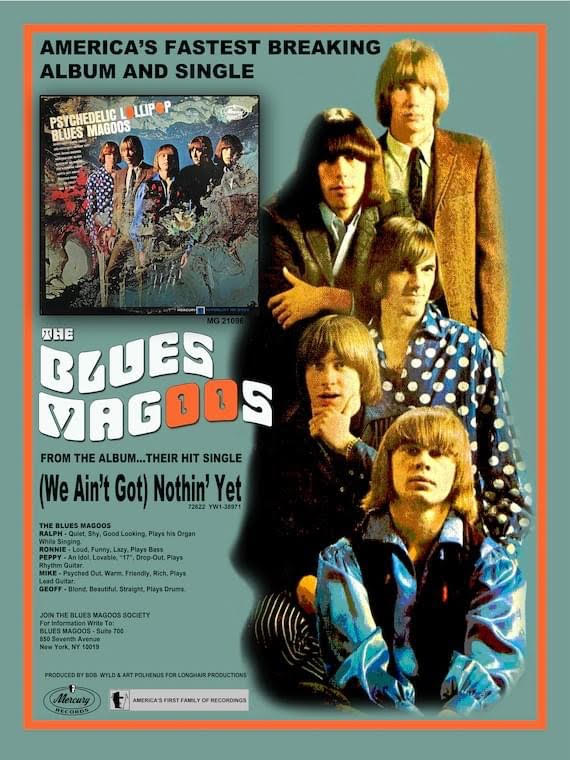

Okay. Well, let’s move on. Your first album, Psychedelic Lollipop, came out in November of 1966– 58 years ago. You were pretty young at the time, weren’t you? How old were you?

Castro:

Yeah, I was 17.

LeValley:

17? Okay. So you were still a high school-age kid.

Castro:

Yeah.

The rush of hearing yourself on the radio as a little kid, teenager was beyond magical. It was not to be believed. It was a total high.

LeValley:

You guys had a number 5 hit in the US shortly thereafter with “(We Ain’t Got) Nothing Yet”. What was it like hearing your song on the radio for the first time?

Castro:

Like dropping acid in heaven. I mean, it was… Because in those days, FM was just starting. So AM controlled the roost, and you didn’t get on radio in LA or New York unless you were top 10 or top 20. If you listen to all those stations back then, they say, “We play the hits and only the hits”. They weren’t kidding. It was like 20 songs in rotation all day long. You didn’t get on there unless you were a hit everywhere else in the United States. So really, the first time I ever heard it was in the Midwest. The rush of hearing yourself on the radio as a little kid, teenager was beyond magical. It was not to be believed. It was a total high.

LeValley:

Yeah, I can imagine. The band’s use of the term “psychedelic” in the name of the album preceded the psychedelic music explosion. I think there were only two bands up to that point who had used that term in an album title. What inspired you to use that word, and did it feel risky at the time?

Castro:

Well, we got banned. Our second single got banned, if you want to know about it, I’ll tell you that. That was the precursor to being a one-hit wonder. But as I said, we were pretty aware of everything. Like Gram Parsons was the first person to get me high on weed. This is all the running around. Mamas and Papas are just coming up out of the Village. Everybody knew The Monkees were being put together as an act. We were all like, freaked out by that and stuff. Our guitar player, a guy named Mike Esposito, was an incredible artist and an incredible musician. He’s an incredible musician. He’s got 10 years on me, and so I learned a tremendous amount of things from him musically. I looked up to him because he was just a consummate artist. He had a painting he had made, which he called Psychedelic Lollipop. And this was 1966. So he had this thing, probably started maybe in ’65 or something like that. His father was Brigadier General Vincent Esposito, who wrote the Encyclopedias of World War I and II for the United States Army. And all his brothers were the youngest colonels and captains in Vietnam.

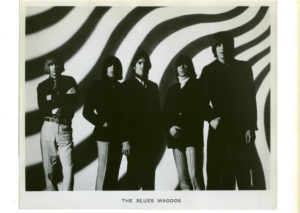

Courtesy of Peppy Castro

Castro:

He was the black sheep of the family, this peacenik consummate artist. And so when it came time to come up with an idea and a cover, he told us about this painting called Psychedelic Lollipop. And because everybody’s starting to drop acid all over the world in LA and New York, we thought, whoa, Psychedelic Lollipop. That’s like licking a stick of acid or something. So we thought that was just too trippy. And then we took his painting and superimposed our photos inside the painting. But it really became the title and the concept because Mike had told us that he had did this painting called Psychedelic Lollipop.

LeValley:

Had you guys already taken acid and that thing by the time that record came out?

Castro:

I have to think about that one.

LeValley:

Had you already been psychedelicized?

Castro:

Yes, we were definitely psychedelicized. I think we were probably psychedelicized after the release of the record. And mind you, when you’re a band and you have a record called Psychedelic Lollipop, you can’t go anywhere in the world without being stopped, strip-searched at every airport and stuff like that. Then at every gig, there’s a ton of kids that just want to turn you on, that just want to get you high. The tour that the Magoos did in ’67 was the Blues Magoos. We opened, the Who followed us, and Herman’s Hermits was the headliner, and we went out for the whole summer of 1967, and this was the tour that broke The Who in the United States. Every night, I’d be going out with Townsend and stuff like this. People would be coming up to us at the after parties and saying, “Here, try this”. What is it? They go, “Oh, we can’t tell you. That would ruin the high”. Pete and I would go like, never mind. But because we were of the psychedelic ilk, there were hippies all over the United States that the feather on their cap and the big rush for them was to know that they could walk away, and they turned on the Blues Magoos at the end of the gig.

Castro:

So there was a lot of funny shit going on. But I was in the apartment. I mean, I left home at 14. And by the grace of God, a truant officer forged my birth certificate so that I could legally get signed out of the school system. That’s a whole other story in itself. But because they were going to put me away, because you can’t be on the streets of New York at 14 and 15 years old, and you can’t even leave school unless you have your parents’ consent. So this guy did me a very good solid, and he forged my birth certificate so that two months before my 15th birthday, he had it that I was turning 16 instead of 15, and then my mother was nice enough to cosign a release. So, I legally got signed out of the school system two months before my 15th birthday. So, I’m running around the Village. Yes, no, I don’t want to drop acid yet, but everybody else is going pretty wild, and I’m just taking it all in. And like I said, I started weed off with Gram Parsons, who had a band called the International Submarine Band at the time.

People would be coming up to us at the after parties and saying, “Here, try this”. What is it? They go, “Oh, we can’t tell you. That would ruin the high”.

LeValley:

Okay. Was this before the Blues Magoos had that hit song?

Castro:

Yes, this was before. Yeah.

LeValley:

Okay. Well, your first three albums were definitely psychedelic, but you went in a different direction with your fourth album, which was called Never Going Back to Georgia.

Castro:

What a story that is. Oh, my God. You got it here? You got it up? I said you got enough time?

LeValley:

I don’t know. What motivated you to change your sound at that point? It was 1969.

Castro:

Yeah. Well, first of all, it wasn’t only the sound, it was the whole band. You see, what happened was when I was wondering whether I was going to be drafted at 18 years old and stuff like that, and the band was becoming very popular. If you listen to the third record, Basic Blues Magoos, there’s a progression in our songwriting that’s going more psychedelic, but there’s a little more melodicism going on, and we’re maturing as songwriters. The other guys decided in 1969, Peppy, we do not want you in the band anymore. I was crushed. At this point, I was 19 years old, and we’re now a one-hit wonder. The money is not coming in. We owe money all over the place to the photographers and the IRS and the agents and the managers and the producers and all this stuff. The ship is sinking because our follow-up single “Pipe Dream” got banned by the ABC Network. They called us up and said, “This is too psychedelic. It refers to drugs. We can’t play this”. So, they were fearful of us. And instead of us being rebels and getting a bunch of kids to go down to the radio, nobody knew that stuff back then.

Castro:

So, we lost the record, and we got the thing of the one-hit wonder. So by the time, the rest of the guys were pissed off at the managers. I truly believe I was getting too much attention and developing as an artist that they decided they wanted to go to California by themselves and be the Blues Magoos, and they just said, “You’re out of the band”. Oh, wow.

LeValley:

So you were the front man, but they kicked you out of the band.

Castro:

Yeah. Well, I was the front man with Ralph Scala. Ralph and I split the vocals, but Ralph was the voice on “(We Ain’t Got) Nothing Yet”. I was the secondary voice, the harmony guy with them on it. But yes, they said, we don’t want you in the band anymore for whatever reason. My only saving grace is that I’m the only guy that stayed in the business and had a career and have gold records downstairs on my wall. I’m a musician with a pension, so God bless me for that. I guess it all worked out in my favor. But what happened was that I, at the ripe age of 19, I wanted to start the first Latin band in the United States. This is before Santana ever even came out. FM was balling up and I said, I’m half Colombian. Let me try and maybe I should get it. So I wanted to be the first Latin rock band in history to come out. I started putting a band together with vibes and congas, and I even ended up getting Peewee Ellis, who was James Brown’s musical director, in the band with me. My managers, who were pissed off at the other guys because they were leaving them as well, looked at me and they said, Listen, we don’t like what they did to you.

Castro:

And the office is here. If you want to use the office, the phones or anything to do whatever you want to do in the future, come on up anytime. So they saw me rehearsing this Latin band, and they had turned around to me and said, We own the name Blues Magoos. I was like, What? They said, Yeah, we own the name, and we sold the name to ABC Dunhill. I was shocked. And they said, and we think you were a focus of the group, and so we want you to still be the Blues Magoos. I was like, Yeah, but this is a Latin band. Even at 19 years old, I didn’t want to do it. I wanted to be my Latin band. But then they said, “We’ll give you some money. We think you should do it. We have a record deal sitting here”. And then at 19 years old, I figured, “Well, it may take me a year to get another record deal”. And then I decided in my mind to say, you know what? I want to keep working. Let me keep working. And so, I did Never Going Back to Georgia as really what I should have called in hindsight, the Latin Blues Magoos, which would have been because that’s what it was.

Castro:

But I did that. It got me through the rough years. If I look back, it’s one of the few should have, would have, could have regrets that I went against the grain and I didn’t want to do. But I did it, and that was how that whole thing changed.

LeValley:

Yeah. Well, I can certainly understand your feelings at the time. They kicked you out, and then here you have the opportunity to put out a record as the Blues Magoos–as the leader.

Castro:

Yeah. So if I can, Jason, what happened was when I had the record in the can and it was ready to release, the other guys tied me up in court. They put a cease and desist on saying they’re the Blues Magoos, and blah, blah, blah, blah. And it tied up for nine months. And within those nine months, Santana came out. And I went, “Shit! There goes that”. You live and learn. Yeah. But it got tremendous. Never Going Back to Georgia, it got tremendous airplay in the New York market. And it is what it is. I’m not sorry I did it. It kept me in the business. It kept me working. It kept me maturing. It kept me writing. I expanded what little knowledge I had as a musician by 19 years old. Now I’m an elder statesman.

LeValley:

You stayed in the business, and you were in a band called Balance. I never heard of them, even though this was the time that I was in high school listening to Top 40 music and stuff. But You had a number 22 hit called “Breaking Away”, which I don’t remember at all. I listened to it, but I don’t remember hearing it.

I taught Ace Freely how to play guitar. I’m his inspiration.

Castro:

It’s classic.

LeValley:

Oh, is it?

Castro:

Yeah, it’s a great record.

LeValley:

Okay. Well, how did that band come about and what was your role in it?

Castro:

Okay, so that band came about… First of all, I secured management for myself. I went from the Magoos till I took a starring role on Broadway in the Broadway musical Hair for a year and a half. I did that as well. Then I wrote a musical that ran in Beverly Hills for months and months called Zen Zen Boogie. That led me to other things. One of the things that I’m part of Kiss-tory because I taught Ace Freely how to play guitar. I’m his inspiration. I’m his first inspiration, the reason why he became a musician. At the same point in time that I had Zen Boogie up in… I had it at a little theater in Beverly Hills called the Solari Theater, which was on Canon, north of Wilshire. It was a big hit for me. A 300-seater. It was great. Cher came in and cut one of the tunes out of the show, which is one of my gold records for Cher. I got for Kiss, Diana Ross, a few things like that. And I’ve stayed active in the theatrical thing. Paul Stanley and I became very fast friends. And Paul Stanley sings. He ghosts a vocal on the first Balance record because he loved the band.

Castro:

Paul came into my apartment in New York. This is while I was signed to a management company called Lieber Krebs, and they had 14 platinum recording artists. Paul walks into my apartment one day in Manhattan on 58th Street, and he goes, “Hey, man, I want you to meet my friend Bob Kulick”. I look at Bob Kulick and I went, “Wait a minute”. I know this guy from the Village like 15 years ago. So I go to Bob and I look at him and go, I know you. And so Bob Kulick ghosted a lot of solos on the early Kiss records that nobody knew. And him and his brother Bruce played for a bunch of people. God rest his soul. Bob’s gone now. And once Bob met me, he was on me like flies to shit. He was like, “Come on, Peppy, you got management. We should start a band. We should start a band”. And so that was the birth of Balance that Bob’s insisted to do this, and everybody seemed behind it. Me, Bob, and a guy by the name of Doug Katsaros, who was on my end for years and years and years, who’s a complete consummate, incredible musician, we decided to start Balance.

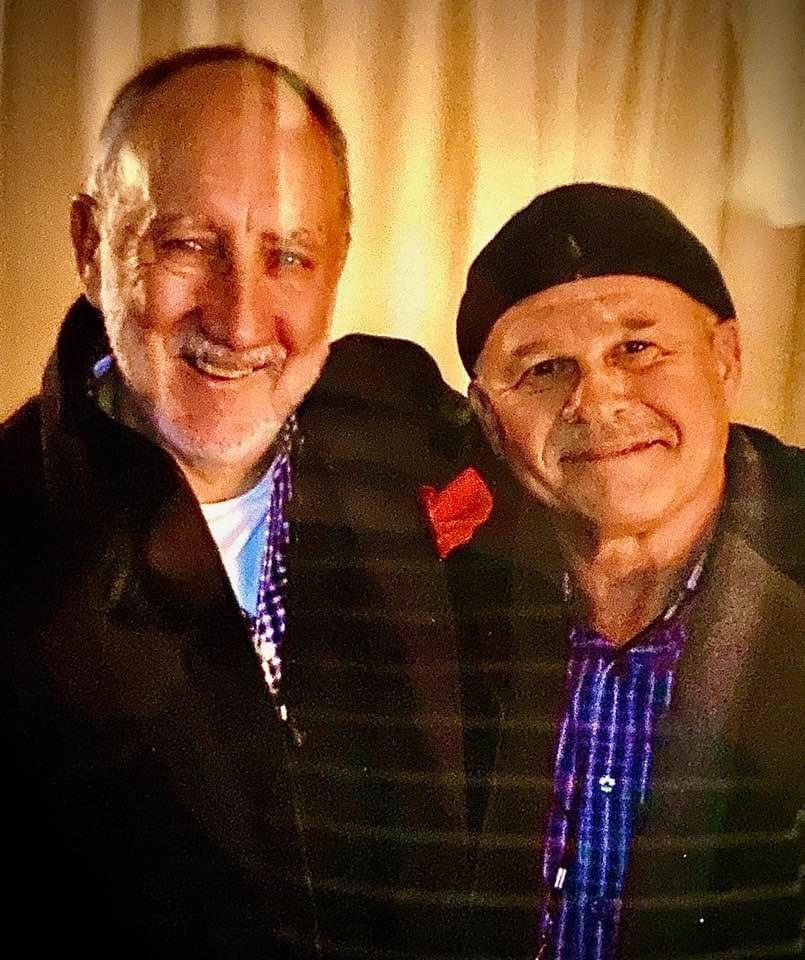

Photo of Pete Townshend and Peppy Castro courtesy of Peppy Castro

Castro:

The original band the first album, you have, I don’t know if you know who Andy Neumark is, but Andy and a guy named Willy Weeks made an amazing amount of top hit records, and they were Riff Martin’s rhythm section on many, many records. Riff was like Atlantic’s George Martin. He was the guy at Atlantic. We had a bunch of heavy hitters. The concept was to be like a New York Toto, to just handpick killer, unbelievable gession Guys. We got a deal in a minute with the epic portrait and stuff. They put out the first album. “Breaking Away” went to 22. I still get phone calls from guys I really, really respect, A-list songwriters who tell me that “Breaking Away” is one of their all-time top 20 records.

LeValley:

So, you wrote that?

Castro:

Yeah, I wrote that in 20 minutes.

LeValley:

And you sing it also?

Castro:

Oh, yeah, I sing and wrote it. I basically did the main frontman stuff in balance, wrote the majority of the material, and the band was revered in Europe. Our second album was voted album-of-the-year in Kerrang magazine over there. So we’re one of those should or would have, could have. But if you listen to it, it’s really me in my prime. I’m like a vocal Superman on this record. It’s probably one of the best musical bands I probably ever did. It’s a great band. It was killer.

LeValley:

Is there anything that you wish you would have done differently career-wise?

Castro:

Two things. Yeah. One was the Latin Magoos. I don’t regret it, but I wish I would have had that door number one or door number two window, the tunnel vision to go, I wonder what would have happened had I just called it Asuego Up My Butt, you know what I mean? And just came out as a Latin band, and I wonder what that would have happened. And the other thing is that when I was in Hair on Broadway, I had two principal roles. I had contracts for two principal roles, and I did the shows, and I had a tremendous amount of hair, obviously. God laughs. And so I had two principal roles in the show because the guys who wrote the show had run on the show’s contract, and they could come into any show in the world. As long as they got there before a half hour, they could say, I’m doing the show tonight, and I would have to pull it over and do another role, depending on if they walked in at the Biltmore Theater on Broadway and said, “We want to do the show tonight”. So one day I got a letter in my mailbox, and it said, We want you to go up for a new show.

Castro:

We saw you do the show. We think you’re fabulous. We think you’ll be great for this. They wanted me to do an audition for a brand-new show that was going to be called Pippin. I thought to myself, Well, music’s my thing, but if I’m going to stay in theater and I can now be in the original, as somebody who originates role, then it’s worth it for me to stay in theater. Nine callbacks I had for this show. So I was like a basket case by the fourth, fifth thing. Equity had to start paying me for the callbacks because they couldn’t abuse you that much under equity rules. And I was now a union member for live theater for Equity. And they said, “No, if you want this guy to come back for more auditions, you got to start paying him for these things”. So by the ninth callback, I’m like a basket case because I know they went to 500 guys in LA and 500 guys in New York. When I go for my ninth callback, it’s me and one other guy whose name is John Rubenstein, who’s Arthur Rubenstein’s son. And so, I go back and there’s a work light and me and this guy and all the suits come up and go, “You guys were great”.

Castro:

Oh, my God. You beat everybody out. It’s good. Thank you so much for all you did and stuff like that. But obviously, we only have one rule for someone show. And I went, That’s it. I’m done. John Rubenstein is going to get the role. So they go, So, Peppy, we’re going to go with John, but we want you to be the understudy. And I was like, Oh, okay. So I turned around to him and I said, “Let me ask you something”. The show opens up in New York, and I’m all of 19, 20 years old. I said, “The show opens up in New York. It’s a big hit. You go to LA and open up?” They went, “Yeah”. I said, “John goes to LA and opens the show in LA?”” They went, Yeah”. I said, And I said, “And you guys bring in a big name to assume the role to sell tickets?” They went, “Well, yeah”, I went, “See you”. I walked. I walked away from it. I walked away from a paycheck. I walked away. And my regret is, again, the tunnel vision. I wonder what my life would have been had I kept the understudy role and stayed within the theater ranks and maybe my whole life would have been better.

Castro:

Those are the only two instances in my whole life that I have any, I wonder, should’ve, could’ve.

LeValley:

Yeah. All right. What’s one Blues Magoos song that you wish more people would hear?

Castro:

Wow. Actually, I have one I did for posterity that’s on YouTube now that I just put up for myself that nobody even knows about. That’s called “Nowhere is Somewhere”, which you can find on YouTube, which I did a year ago, something like that, which is like a capsule of something. But the third album, which was not as successful as the first two, has some really cool gems on that. I would say instead of a song, I would say… That’s a nice question, too. Nobody’s ever asked me that one. But Basic Blues Magoos is really a gem.

LeValley:

Yeah, I’ve heard that. It’s very highly regarded, although it didn’t have any big hit songs on it.

Castro:

Yeah. We didn’t have the promotion or anything. Nobody was behind this space. And we cut it with a remote outside our house. So we didn’t do it in a recording studio. But there’s some really fun things on there. That I like.

LeValley:

I know that you put out an album 10 years ago called Psychedelic Resurrection, or the Blues Magoos did.

Castro:

Yeah, with the Magoos thing.

LeValley:

But was that you and original members or…?

Castro:

Yeah, that was me basically, and Ralph, the original singer, and Geoff Daking, the original drummer.

Castro:

Ron, who’s passed away recently, who was the bass player, is our first loss of an original member. He had health issues. He didn’t want to do it. Mike Esposito, I mean, I’m 75 now, so Mike is 84, 85. He was like, “No, count me out. I’m there in spirit. I’ll play a cowbell or something like that”. But since Ralph was the vocal sound and I was the vocal sound and Geoff wanted to be part of it. I did it just to go out on a little bit of a high so that for whatever segment of people out there that still remember or love the Magoos, that it was just something I did for myself. I never knocked on a door for distribution. I didn’t do any of that stuff. I just put it into the universe to see if anybody would like it. There’s some nice fun stuff. We recut one or two of the old original things as an update, but we wrote some fun stuff, too. That was it. It was just to put a cap on it for myself.

LeValley:

Okay. Last question. Who’s your favorite band or artist that’s come out more recently, say in the last 10 to 20 years?

Castro:

Oh, fuck. Maneskin. Maneskin.

LeValley:

Maneskin. Maneskin, okay.

Castro:

Yeah. They’ve peaked now and they’ve come down, but they’re fucking fabulous. Their fucking stage presence, everything about them. I was like, glued. When I hit on them early on, I was like, oh, man, look at Little Italian kids came out of nowhere and they’re killing it. There’s like something for everything. They’re like, woke, they’re not woke, they’re this, they’re that, they’re trendy, they’re not trendy, they’re hip, they’re too cool. They’re Euro. They blew me away. I love them. I thought like, Oh, this is great. And then I got a kid who’s 36 years old. He was like, “Dad, you got to hear this. You got to see this one. You got to see that”. So It filters down to me and stuff like that. But I’m still active. I still do a lot of things. I have six songs in a new musical about Andy Warhol that’s going up in the UK in 2025 with Sir Trevor Nunn is the director, and he’s also my lyricist, which is cool. That’s sanctioned by the Warhol Foundation. That’ll give me another 15 minutes if and when it gets something to get me off the beach. Because I spend most of my time down in Florida.

Castro:

I’ve got a house built in 1760, which I’m in now. This is my little cubby hole in about an hour and a half out of Manhattan in New York. And so, I’ll head back down to Florida again. I prefer it. You’re out in Arizona, yeah?

LeValley:

I am, yes.

Castro:

Did I lose you?

LeValley:

Yeah. Arizona.

Castro:

There you are. Did I put you to sleep?

LeValley:

No, I think the Internet connection became unstable. But yeah, I’m in Arizona, where it’s nice and warm.

Castro:

Nice and dry. Yeah.

LeValley:

And dry.

Castro:

The whole deal. Summer, though.

LeValley:

Yeah. Well, you get used to it.

Castro:

Yeah. I’m afraid you even drive in the streets out there in summer, I think the tires are going to melt.

LeValley:

Yeah. They somehow never do.

Castro:

Yeah. Listen, I’m happy to send you anything. I’ll send you that little video. Okay, great.

LeValley:

Well, let’s wrap this up. So, thank you, Peppy, for being my guest today. I really appreciate talking to you and for taking the time.

Castro:

Skip out, flip out, trip out, turn in, tune in, drop out, all that good stuff. All right. My pleasure, man. All right. And you’re definitely a better-looking Timothy Leary.

LeValley:

Oh, thank you.

Courtesy of Peppy Castro

Gallery

Recent Articles

Can Molly Mend Your Marriage?

•

February 16, 2026

Immer Für Immer by Flying Moon in Space–Album Review

•

February 13, 2026

Loading...

1 thought on “Interview: Peppy Castro of The Blues Magoos”

Thank you pepe. You seem like a fine person.