Psychotropic Cinema: Yellow Submarine

Psychotropic Cinema: Yellow Submarine

Yellow Submarine

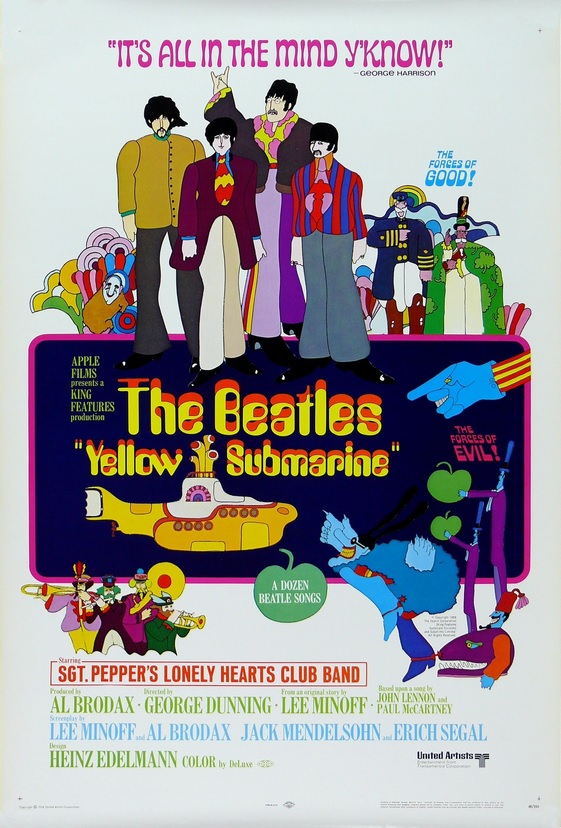

Directed by George Dunning, 1968

When Beatlemania was experiencing its first giddy wave, the Fab Four and their manager Brian Epstein carefully plotted the next steps in the band’s unprecedented career. In late 1963, Epstein signed an agreement with United Artists for three feature films, which went into production as soon as the initial deal was struck. 1964 saw the release of A Hard Day’s Night, the now-classic black & white showcase that has both wonderful songs as well as funny satire and clever dialogue. By the following year’s Help!, the band had discovered the joys of marijuana, which altered both the onscreen comedy (Producer: “Boys, are you buzzing?” John: “No thanks, I’ve got the car!”) as well as the subject of the film’s songs.

The Beatles themselves were changing, growing, adapting. By late 1965 into early 1966, they were experiencing several unpleasant situations on their nonstop world tour. Throughout this time there was a lot of talk regarding the third contracted Beatles film. Several scripts, plots, and outlines were commissioned and rejected. When the tour ended in August, a few weeks after the release of Revolver, they successfully negotiated a vacation for all four — the third film would wait. Paul went off on holiday with Jane Asher, George went to India to study sitar with Ravi Shankar, while both John and Ringo went to Spain, where John was filming his supporting role in Richard Lester’s How I Won the War.

1967 brought “Penny Lane” & “Strawberry Fields Forever”; Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band; “All You Need is Love”; and then Magical Mystery Tour. Unfortunately, Brian Epstein died from an accidental overdose, which threw The Beatles’ financial and legal commitments into chaos. But just before his untimely death, Epstein had negotiated with United Artists what would fulfill the band’s commitment to a third film. Beatles songs (some from the most recent releases, with an unspecified number of “new” songs to be determined) would be used and a script had begun to be written for an animated adventure. The studio to be used was King Features in the US — they had been responsible for the Saturday morning cartoon of the band.

The Beatles were indifferent at best towards the project. They didn’t want to commit to voicing the script’s lines, and they eventually agreed to use four new songs — all had been worked on in rough demo form during the Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour sessions — in other words, they gave the animators their scraps, songs that they hadn’t quite finished yet. But when they began to see the style and uniqueness of the first sequences, they were won over, doing promotion for its release and filming a brief cameo that appears at the film’s end. By the time the film premiered in the summer of 1968, psychedelia was still in full swing throughout pop culture. The film stands as a testament to the power of The Beatles as a cultural force. Fifty-seven years after its release, it still amazes. It is simultaneously a candy-colored child-appropriate fairy tale fantasia, as well as a brain-melting lysergic psychedelic masterpiece.

United Artists / Supafilms Ltd.

In addition to director Dunning, the most important creator of the style and look of the film is Heinz Edelmann (“the German Peter Max”) whose unbridled imagination and flair for visual puns is woven into every frame of animation. Every element, from the watercolor backgrounds to the surreal creature design, the groundbreaking animation incorporating photographs and live-action filmed segments, and the pun-heavy wordplay, are distinctly psychedelic, as are the Beatles songs chosen for the project. Eleven full songs are given life and spectacle by the animation team. They range from older tracks like Rubber Soul’s “Nowhere Man” to the four new songs. In addition, snippets and excerpts from five other songs are used at various moments: a few seconds from Revolver’s “Love You To”; the crescendo from “A Day in the Life”; an oddly echoing sample from “Think for Yourself”; the opening chords to “With a Little Help From My Friends”; and a few seconds from “Baby You’re a Rich Man”.

Each song has a specific style and playfulness. Of course, Revolver’s “Yellow Submarine” was the catalyst for the entire project — it is used in the film’s opening credits. But each segment is bursting with vibrant color and detail: urban photorealism and film-loop magic (“Eleanor Rigby”); typography and whimsy (“When I’m 64” with its demonstration of sixty seconds); playful perspective shifts and backwards dancing (“Nowhere Man”); 1930s stars rotoscoped into blurred colorbursts (“Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”); and plot-driven character interactions which further the story (“Sgt. Pepper,” “All You Need is Love”).

For the four new songs, even more special care was put into their visualizations. For the singalong “All Together Now,” the animators use the song twice. First as they pilot the submarine, and then at the end of the Beatles cameo — with the phrase translated into multiple languages. George’s two contributions are the most psychedelic, with “Only a Northern Song” incorporating images of each member with optical illusions and footage of audio wave frequencies, and “It’s All Too Much” showcasing the victory over the Blue Meanies as well as some truly astonishing images and kaleidoscopic visual patterns. John’s “Hey Bulldog” was cut from the original American release, but is thankfully included in all versions now available. Focusing on the Cerberus-like creature used by the Blue Meanies, the scene has some clever visuals, and the song itself is a propulsive boogie with nonsense lyrics.

United Artists / Subafilms Ltd.

Apart from the four new songs and the cameo at the finale, The Beatles themselves had little to do with the production. Their voices were portrayed by a small cast of seasoned professionals, with John Clive doing the voice of John, and Geoffrey Hughes portraying Paul. George might sound different in certain parts of the film because Peter Batten, the actor hired for the role, was actually a British Army deserter who was arrested while recording was taking place. The remaining sections of the film saw Paul Angelis voicing his lines. Angelis had quadruple duty, as he also voiced Ringo, the Chief Blue Meanie, and the narrator at the film’s start. Dick Emery voiced multiple characters as well: he’s Jeremy Hilary Boob (the “Nowhere Man”), the Lord Mayor, and Blue Meanie assistant Max.

I have been an obsessive Beatles fan all of my life, and “Yellow Submarine” was their first song I heard; it was the mid-1970s (my childhood) on an episode of the PBS kids show Zoom. A public library screening a few years later was my introduction to the film, and generated a love for clever wordplay, colorful strokes of imagination, and surreal adventures. The experience of watching it has changed since then, but not the astonishment at the unusual, the delight in the humor and wit, or the joy communicated in the songs. As a film that both young children and stoned adults can enjoy unironically, it is a rarity of popular entertainment, as well as a showcase for some extraordinary animation. While it is firmly rooted in the psychedelic counterculture of 1965-68, it is also timeless, not unlike The Beatles themselves.

Yellow Submarine is available to stream on Apple+, and is available on DVD and Blu-ray.

— Jeff Broitman

Gallery

Recent Articles

Can Molly Mend Your Marriage?

•

February 16, 2026

Immer Für Immer by Flying Moon in Space–Album Review

•

February 13, 2026

Loading...