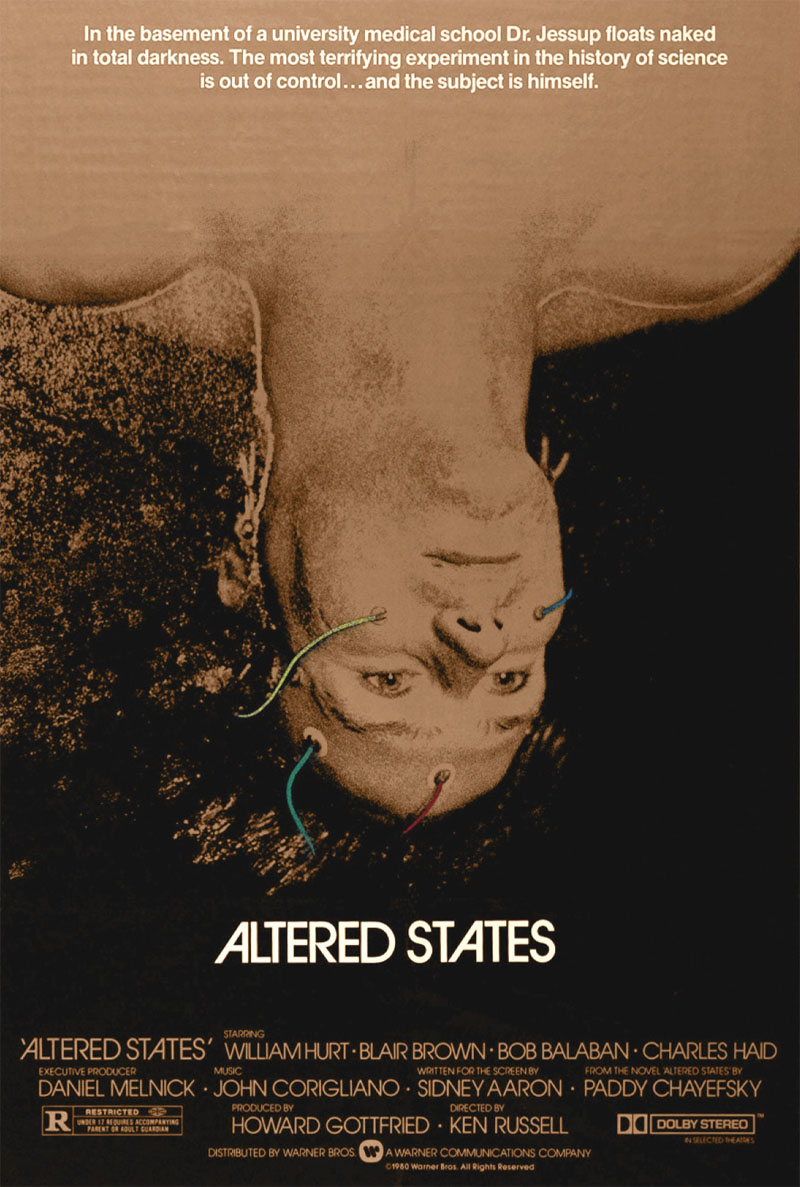

Psychotropic Cinema: Altered States

Psychotropic Cinema: Altered States

Altered States (1980) is a film of monumental magnitude and great importance to the psychedelicized among us. The plot revolves around the dangers inherent in the quest for universal knowledge, facilitated by the use of sensory deprivation interwoven with the use of ancient mind-altering compounds. The movie is a deep dive into the search for meaning of the true self–a cautionary tale of birth and rebirth in the psychedelic cycle of life.

The kernel for Altered States manifested itself during a dinner conversation between screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky and his friend, director/choreographer Bob Fosse. The idea was to make an update of the Jekyll and Hyde story. Chayefsky had previously won Oscars for Network, The Hospital, and Marty and had a reputation around Hollywood for being a domineering pain in the ass when it came to

The movie is a deep dive into the search for meaning of the true self– a cautionary tale of birth and rebirth in the psychedelic cycle of life.

getting a film made. He was the only screenwriter who was allowed to have any say on how a film was shot and produced, often hanging around the set and giving directorial instructions. Director Ken Russell started his career making historical docudramas about the lives of classical composers of the Romantic era. Russell’s innovative use of surreal dream sequences became his calling card, noted in such films as The Who’s Tommy, Mahler, and The Boy Friend. According to Ken Russell’s autobiography Altered States, twenty-six other directors either turned down the offer, were fired, or quit before Chayefsky got to Russell. The last of those was Arthur Penn (Bonnie and Clyde, Little Big Man) who was fired after a dispute with the notoriously difficult Chayefsky.

It had been a long time since Russell’s films were Oscar-nominated or lauded by critics. His late Seventies films had flopped at the box office, and he was struggling. He had also never worked within the Hollywood studio system, opting to make smaller British films. That is why Russell was surprised to hear from producer Howard Gottfried, asking if he wanted to take a meeting with Chayefsky, the hottest screenwriter in Hollywood at the time. It should have been no surprise for him to be asked to helm a production regarding psychedelic research given his penchant for outlandish visions of dream life in his previous works.

The plot of Altered States begins in the late 1960s, where Dr. Jessup (William Hurt in his film debut) is a psychopathologist studying schizophrenia and altered states of consciousness via sensory deprivation. Several years later, Dr. Jessup took his research to another level by visiting a Hinchi tribe in Mexico and partaking in one of their sacred rituals. The tribe used a potion made up of the mushroom Amanita Muscaria and the shrub Heimia Salicifolia (don’t try this at home) to enter into a hallucinatory state. The Hinchi called this shrub Sinicuichi or “first flower” because of its ability to unlock primordial memories genetically filed and locked in the human mind. After some psychedelic shenanigans ensued during this ritual causing Jessup to be summarily dismissed from the tribal ceremony, he took some of the potion to study and synthesize in his lab.

Jessup’s research team consisted of Arthur Rosenberg (Bob Balaban) as the “Igor” to Jessup’s Frankenstein, a facilitator to the mad scientist. A second colleague Mason Parrish (Charles Haid) was a practical man of science who was cautious and consistently tried to reel in the dangerous nature of the new scope of work. Because of the toxicity of larger doses of this compound, Jessup paired it with his sensory deprivation experiments, believing he could go “further out” without the danger of taking too much of the drug. And further out he went! Physical devolution into a protohuman caveman and then reconstituting back into human form, which is a pretty cool trick. The only problem is the drug hung about so long in the body that he started to transform involuntarily during off-experimental hours. After waking up naked in a zoo (as sometimes happens with these things) following a Neanderthal’s night out in the city streets, his colleagues expressed concern and begged Jessup to stop any further experimentation. A decision was made to do one last experiment under strict supervision. This is when all hell breaks loose. To not spoil the plot, I’ll end it here but WOW! What a story.

The dreamlike hallucinatory visions are superb in the film. Many are religious in nature, which is a hallmark of Russell’s work. Paired with practical effects by makeup genius Dick Smith (The Exorcist, Little Big Man), everything seems so real and unreal at the same time. This film contains the first use of innovative pulsing and breathing “bladder” effects that I can recall beyond their use for gunshot squibs, which Smith had himself created for The Godfather.

The struggles between Ken Russell and Paddy Chayefsky were visceral in this production but thankfully didn’t make it to the screen. Russell was unused to having a screenwriter take over the set. After Russell banned Chayefsky from the set for being too much of a distraction, he tried to have Russell fired. The producers at Warner Brothers told Chayefsky that unless he took over direction himself, he couldn’t fire Russell. They were too deep into production to lose director number 27! In the end, Chayefsky was so disgruntled he had his name taken off the film and it would be his last screenplay. He died of cancer a year later. Russell would continue to direct, signing a multi-picture deal with Vestron. He made many more films with a couple of them being great, very worthwhile watches such as Gothic (1986) about the night Mary Shelley decided to write Frankenstein, and Lair of the White Worm (1988) from a Bram Stoker novella. Russell died in 2011 after a series of strokes.

Gallery

Recent Articles

Loading...