Interview with Robyn Hitchcock

Interview with Robyn Hitchcock

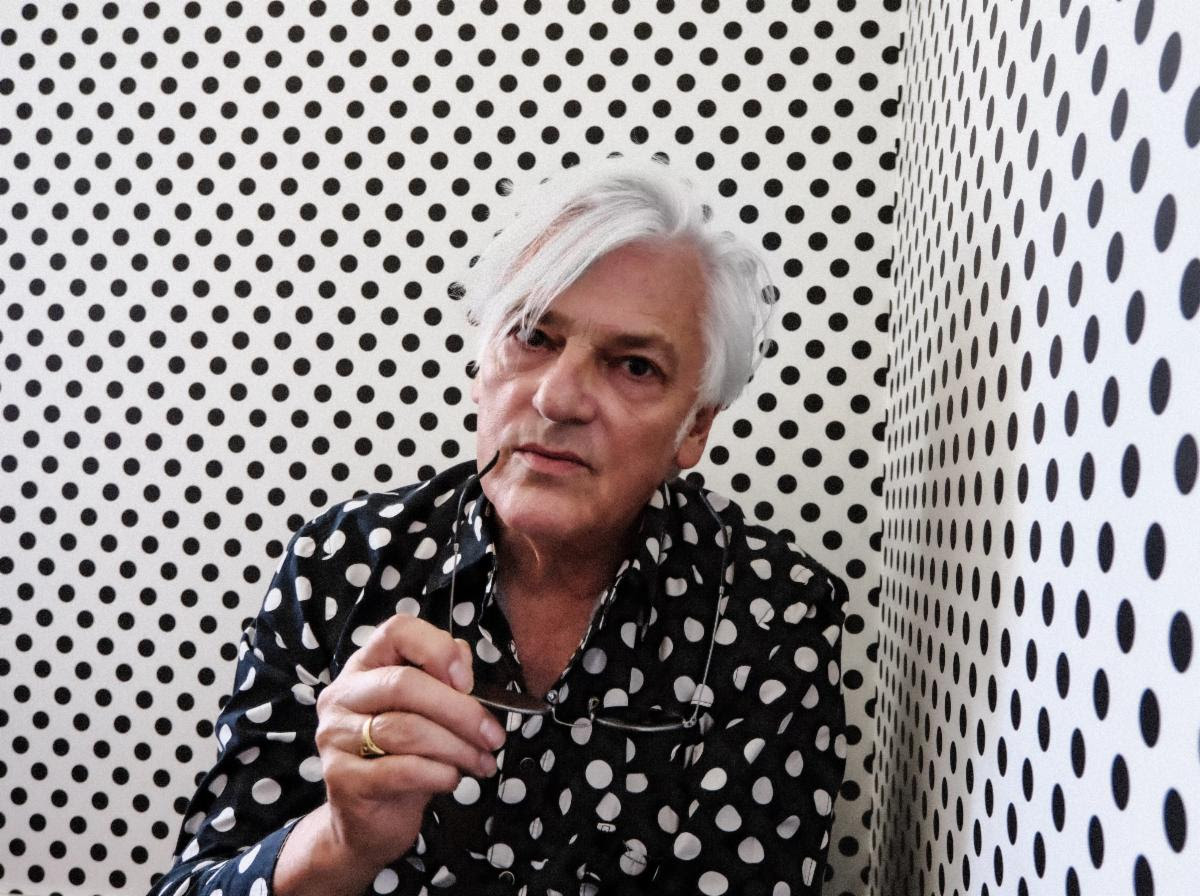

Robyn Hitchcock–Date of interview: July 22, 2024

Cavenagh:

First of all, thank you for doing this. I really appreciate you fitting me in. How much time can you give me?

Hitchcock:

45 minutes to an hour. Hour tops.

Cavenagh:

Perfect. Perfect.

Hitchcock:

But that should give you enough time to discuss all you can bear to think of and more on these particular topics.

Cavenagh:

Yeah. So I’m sure you’ve been doing a lot of the same kinds of questions over and over again. So I’m hopefully not going to ask all of the same ones. But I guess my first question, which is the chicken or the egg question, which is, which came first, the album or the book?

Hitchcock:

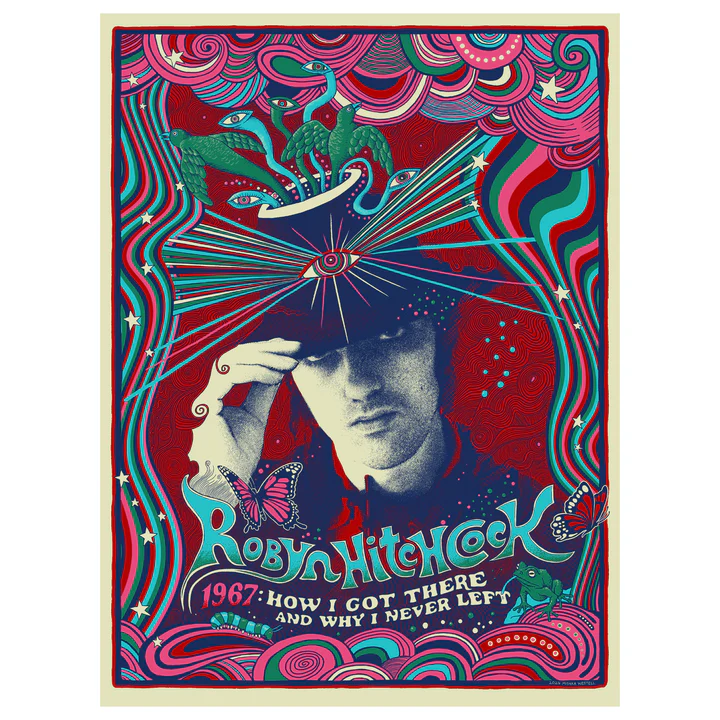

Oh, the book. Totally. The album is simply there to go with the book. It’s a companion piece, if you like. It just seemed like because the book was getting published, it would be a nice flourish to have the album come out afterwards as a sort of “and here he is singing some of those songs,” you know because they’re also because the songs some of those songs were part of the fuel that combusted in me to launch my career. So the book is basically a… it’s basically context. It basically explains why I became what I became. So rather than writing a book about my career, I thought, “Why not just write about why?” you know…

Cavenagh:

I get it. And I love the way in the first of all, I very much enjoyed the book.

Hitchcock:

Oh, thank you.

Cavenagh:

I like the way that you kept referring to the turntable or the hi-fi that was at Winchester. You talked about it in such reverent tones because it was a new thing to you at first. And then it became a source of fuel for you. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Hitchcock:

Well, it was the Oracle, really. You know. We didn’t have radio or TV. We did have the newspapers for what they were worth. Every day they would turn up on the table. The big table in the hall around which we all had our little modules that we sat and wrote in, worked in. But the record player, the house record player, was just a wooden… it was a turntable that some boys, I guess, had rigged up themselves with a quite powerful speaker. It was just mono, but you could definitely blast out all over the hall. And I think everything was in mono at that point, 1966. But whoever had records could play them. And there would be often there’d be a break and people would rush sprint to the record player to see who could put a record on first. Because obviously, what you played might not be to other people’s tastes.

So once I got in there, I inflicted far more Bob Dylan on people than they necessarily wanted. You know. And there were people who liked the Monkees and people who liked the Beach Boys. And then there were people who liked Bob Dylan and jazz. And then there were people who liked the Beatles, and just about everybody liked the Beatles. The Beatles was what everybody had in common. It was a sort of meeting place. So you know a few people had their own little cells that they were allotted, and they had record players in there. And after a while, I got my own portable record player. So I’d go and climb up the hill or walk into the water meadows or go into a distant gallery somewhere. And you know I’d play music portably. In the days before people had personal hi-fis, let alone iPhones, you know let alone streaming. In those days, you had to carry the record and the record deck with you, which we did because music was so important.

Cavenagh:

So one of the things that I have always admired about you and your lyric writing, which I saw not surprising in the way that you write prose, is your gift for – and I’m not just blowing smoke – but you have a very noticeable and recognizable style. And can you talk a little bit about how your writing style evolved versus your lyric writing style?

Hitchcock:

I’m not aware of having a writing style. You know I know who influenced my lyric what influenced my lyric writing, if you like. But I’m not aware of a prose style at all.

Cavenagh:

Well, let me take a step back then.

Hitchcock:

I’m very honoured, flattered by what you say, but I don’t think of myself as having a prose style, really.

Cavenagh:

Well, if anything, I think maybe it’s your turn of phrase and the way that you describe things. So you could feel the cold walls of Winchester while I was reading the book. And you know…

Hitchcock:

Oh, really?

Cavenagh:

You were talking about the places you were going and, you know, being on the street. And you gave the reader a sense of what you were experiencing and recalling at the tender age of 12.

Hitchcock:

Wow. Well, that’s really good. I mean, I think partly it’s because what I was writing about. That was the most vivid time of my life. I was going through puberty. And I was in a world that was changing as fast as I was. So for about 18 months, the world and I were keeping pace. You know. Then the world raced ahead. But that was my accelerated time, and that’s when I was at my most intense. So I think I felt everything very strongly, and that probably comes through when I write about it. You know. It’d be interesting to see if I wrote about 1987 or, you know, 2003, whether I was able to make people feel to conjure up that feeling, that would be an interesting experiment because by that time, you know real life had asserted itself. And real life is so much about being diluted and compromised and so much about having made mistakes that you have to try and live with or rectify. You know. You’ve got all that baggage and all that sort of beige membrane that grows up around you. And of course, with 13, 14, you should, anyway, have none of that.

Cavenagh:

Right. You’re just a tabula rasa. You are ready to be written.

Hitchcock:

Yeah. Yeah. You’re ready to be written or you are writing, you know and it’s the first couple of pages. So the paper is very smooth and your nib is sharp.

I remember reading Roald Dahl books when I was a kid. And, oh yeah, he was always writing about being in those horrific schools. And sorry, sir, I had a bust nib. And I remember asking my dad, “Dad, what’s a bust nib?” Because my dad went to school in England for a time. Oh, yeah. And he said, “Oh, it’s a pen tip for a fountain pen you dipped into ink. And if it was broken, you were nowhere.” And so that phrase has always reminded me of Roald Dahl and the tortures of his childhood in public school.

Hitchcock:

Oh, yeah. Gosh. Well, he probably had a worse time of it than I did. Mine was quite humane, really.

Emma Swift

Cavenagh:

It sounded it.

Hitchcock:

But we did have fountain pens. I mean, I use a fountain pen now. Track down ones that are easy to you just put a cartridge in them and things, but I much prefer writing with a fountain pen.

Cavenagh:

So one of the interesting things I got from the book was the way you described it. It wasn’t so much a hierarchy of your classmates, but just where everybody kind of slotted themselves in, where you had the people that liked The Monkees, and then you had the people that liked I don’t remember what your first reference was, but you had kind of a spectrum of what people liked and how that kind of dictated their social standing on some levels. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Hitchcock:

Well, I think also their social standing dictated what they liked. So it’s almost like you know whatever you aspire to, you then find the music that goes with it. Or maybe it all happens in one divine package. So what I call the groovers who basically tended to be the intellectuals, the kids whose parents were probably academics. They liked initially Jazz, and then Dylan, and then Hendrix, and then like I said, The Beatles was common ground. And the meatheads were into much more into the Beach Boys, you know jock music. I mean, not that Brian Wilson isn’t an exquisite and sensitive artist, but sort of the people that picked up on “Fun, Fun, Fun” and “California Girls” and things tended to be much more like that.

You know they were more likely the people who were going to go into the army or to become financial consultants or something. When they were into sport, of course, which the groovers weren’t. And I mean, you could pick your own way. You didn’t have to be a groover or a meathead. And in some ways, I admire people who were more you know selected what they wanted from each package and formed themselves.

But people are tribal and they, especially at that age, congregate to belonging to some kind of tribe, and then that inevitably fits into a hierarchy. So I mean, I don’t think Winchester College is actually any more hierarchical than the music business is. You know There’s definitely pecking orders here.

You know the more people you can play to, the further up the bill you are, the more albums you sell or streams you get, you know the more important you are and the more the people in the lower branches have to defer to you. And then you know the cherry on top is Taylor Swift or Paul McCartney or whoever it is, you know?

Cavenagh:

It’s an accessibility thing at some point, right?

Hitchcock:

Well, you mean whether what you do is accessible?

Cavenagh:

Yeah. Not accessible in access to it as much as you know the Beatles ran the gamut of crazy psychedelia to you know straight up pop. Taylor Swift is probably purely pop. I can’t say that I’ve listened to that much of her music, but I know it when I hear it. But what I’m saying is more of the you know I guess it’s that spectrum of their output that appeals to a broad hierarchy of people?

Hitchcock:

Well, I don’t know. I mean, you mean the Beatles’ output or you mean Taylor Swift’s output?

Cavenagh:

Yeah. The Beatles more than anything. Because I think you were comparing the groovers to the meatheads and I can see how “Fun, Fun, Fun,” “California Girls,” that kind of stuff would appeal to maybe the same kind of people who like “She Loves You,” you know “Love Me Do,” like the more pop. They kind of align. You know.

Hitchcock:

Well, it did. And then, of course, you know Dylan and the drugs came in, and then you got “Good Vibrations.” And as I say in the book, you know somebody turns up from another house, a groover, and says, “You got to listen to this.” And you know we go, “No, no. This is the Beach Boys. It’s for meatheads. It’s not for the likes of us. Oh, but it is, man. It’s jazz with words or whatever. You know I forget what he said exactly, but you know it’s beautiful, man. And it was. It was “Good Vibrations.” And suddenly, you know we were wrong-footed. Oh, my gosh. Look at this. It’s “Good Vibrations”. It’s the Beach Boys. Of course, the meatheads had to like it because it was the Beach Boys. There was some confusion. They didn’t then like everything the Beach Boys did because Brian Wilson started producing stuff like Heroes and Villains and various things that never got finished.

And the Beatles was just the great… everything met at the Beatles. You know The Beatles was like the great hub. The hub from on high.

Cavenagh:

It was a time and place thing, right?

Hitchcock:

Yeah. And it was all time and place, really. And I think that’s why people are interested in it as well. The book has provoked a lot of interest, people, particularly from older people who remember that time, but also just people with a sense of music history. Because so much stems from there and not just music, but culture.

You know, certainly in Britain, by the end of the end of ’67, you know it’s legal to have sex with your own gender. It’s legal to have an abortion. It’s socially acceptable to grow your hair. It’s beginning to be socially acceptable to smoke pot. Nowhere near legal, but it’s not like, “Oh my God, these people are drug fiends.” you know So many of the templates of modern life seemed to be formed then. They were brewing beforehand, for sure, but ’67 is when it actually became visible. It came up above the horizon.

And you know because the Beatles had such a universal appeal, because Paul wrote songs, as John said, that the grannies could dig. Because Ringo was cuddly for all the exploratory nature of George or the acerbic nature of John, you have the other two people who go, “Oh, yeah, come on. It’s no problem.” And so you got the Magical Mystery Tour that was I mean, if people had seen it in colour, I think they’d have been kinder to it.

TVs were so small in those days, but you just got this sort of family psychedelia, really. And you’ve got to thank the Beatles for so much of that making what was difficult seem acceptable. You know Sure, you have the innovators like Dylan and Jimi Hendrix, but the Beatles just got it out to everybody.

Cavenagh:

For Psychedelic Scene, we started a section called the Psych Ward. The Psych Ward is a look back at classic psychedelic records. And yeah, we started with Revolver.

Hitchcock:

Oh, yeah. Good place.

Cavenagh:

And I got to write that review, which was a lot of fun because it’s my favorite Beatles record. So it was a labor of love. But I want to ask you two questions, and they’re both probably going to be a fairly long response. So one of the questions is what we typically ask a lot of people that we interview for the magazine, which is how do you define psychedelic music?

What makes something psychedelic from a musical perspective?

Hitchcock:

You mean psychedelic generally, or you mean specifically pertaining to 1966, ’67?

Cavenagh:

I would say probably more generally because I don’t want to limit you to your potential response.

Hitchcock:

I think of psychedelia as whatever you look at when you look at it closely, it changes. So it always contains something that isn’t immediately visible. So it has a transformative nature. But I mean, the shibboleths, the symbols, the totems of psychedelia, things that I’ve always used, you know like sitars, backwards guitars, phased harmonies, you know just the obvious tool kit from ’66, ’67. But in a more general sense, I mean, I would say that things like Roxy Music, what Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music were doing in the late ’70s, early ’80s, around the time of Manifesto and Flesh and Blood was a kind of it was a kind of slightly decadent, stylized psychedelia, but it was definitely had a lot of those textural elements in it.

I mean, you could argue that it’s just a sense of texture, which is generally something that people become more aware of if they take psychedelics. You know That’s where people first begin to notice or start making unusual noises. I don’t know what psychedelic music is now because it’s probably largely generated by machines, you know dance music, trance music, stuff that’s been going now for 40 years, really.

And I’ve never taken the drugs that you would need to enjoy it. I just never got that far. It seemed to me like it was more regimented and that ecstasy was a more manageable version of LSD. You would never get all those people. LSD made people into cats. They all go off by themselves in different ways.

E and MDMA and all those seem to make people into dogs. They were always happy to be in a pack. They’d all blow whistles and dance and love each other. It was much more manageable. You kind of knew what was going to happen. Just as rock music now, it’s a much more obedient beast. It generates large sums of money, so it’s acceptable for capitalism, and it absorbs people, and it has a stylized sense of rebellion.

If you want to look like a badass now, just be photographed with a cigarette. My God, you’re not going to light that, are you? Marijuana and tobacco have changed places. I don’t know. I mean, I sort of feel like a social historian now. I don’t really know. I’m not really a psychedelic musician.

I have unchained words, and I reserve the right to put anything I want in a song lyrically. But musically, I’m more like just a folk artist, really. You know And I garnish my stuff with a few you know you can hear the record I’ve just done.

It really is campfire psychedelia with a little bit of Mellotron and sitar on it just to kind of show you as a nod to where it came from. But it’s not going to blow your mind.

Cavenagh:

No, I like the campfire psychedelic. Campfire psychedelia is a great reference. It should be an official genre. I’m thinking.

Hitchcock:

Well, it might come in handy in years to come if resources become scant.

Cavenagh:

So let’s take that and not necessarily based on that, but my next question is going to be based on your learning about him and becoming a giant fan and you’re obviously influenced by him. Tell me more about how Bob Dylan figures into not only the book and the period, but after.

Hitchcock:

Well, Bob Dylan was the Big Bang, really. I mean, I’m sure you know lots of ingredients must be there in a parallel universe in order to create a Big Bang. And I guess they were all those things that he absorbed and then he exploded and transformed music. So yeah, his music hit me as a 13-year-old, you know being away at boarding school and away from my family. So within about six weeks, my compass had shifted from mom and dad and sisters and au pair girls and grandma and everything. And it moved around to Bob Dylan, but he didn’t know that and still doesn’t …you know 50, 70 years later.

So it was otherwise one-way relationship. In that way, it’s very like a relationship with God. You have your own personal God and your own personal Dylan. That’s why there’s these sort of internecine punch-ups between different strands of Dylan fans. And you know no, no, no. You don’t understand. Absolutely sweet Marie is about somebody called Marie.

No. It’s someone who was sweet, you know whatever. It’s subject to your interpretation, but it influenced me. It changed my molecular structure. I know I sort of wound up sounding like Syd Barrett, but that was simply because I needed an English approach. I mean, I love Syd Barrett totally, but what I was aiming for was Dylan and kind of slipstreaming Barrett got me into that, whatever that kind of music is, you know visionary music.

I mean, I love Jim Morrison too. I think he’s the ultimate rock star, the ultimate visionary who is also standing there in leather pants wailing around for people to get drunk to. But you know I’m sure he wouldn’t have fared well if he’d lasted. But I think he was the real thing as much as there is a real thing.

Yeah. Dylan just you know he’s endless. He still goes on. He actually, I think, ceases to be the same person after a while. And that’s why people are so baffled by him. Certainly, in the ’60s, he was transforming so quickly. And the gulf between Blonde on Blonde and Nashville Skyline is so vast that he doesn’t even look the same in photos or anything.

You know I think his molecular structure keeps changing. People are just constantly wrong-footed by Dylan, and he knows it, and I think he enjoys it in a way. Maybe he gets frustrated. Maybe he wrong-foots himself, I don’t know.

My favourite quote about Dylan is somebody who I think is a friend of his. I don’t know what he said, “Oh, there’s so many sides to Bob, He’s practically round.” I think you know Dylan is a sphere. All I do know is that when he dies, when he’s gone, there’s going to be an awful coldness that steals over so many of us.

And that even though he’s very clearly not the Messiah and he’s very clearly fallible, and even though a lot of his live gigs have been shit for the past 45 years, and he sometimes doesn’t seem to be a tenth of what he was, he’s still in there and sometimes he can deliver like nobody else.

And you just have to accept this is not something you can fully understand, but it is alive, and it’s still producing things. And so you kind of I don’t feel that kind of adoration, but I still take comfort from the fact that Dylan is there doing his own strange reinterpretations of his songs and coming up with new ones which are at times almost just like lists.

But you know when he’s into it, he’s still great. It’s simply a matter of whether he’s into it or not. Sorry, that’s a very, very long answer, and feel free to prune it.

Cavenagh:

No, no. That was exactly what I was hoping to get. And you gave a lot of detail and descriptive parts that I was hoping you were going to hit. So that was great.

Hitchcock:

Oh, great. Good. Thank you.

Cavenagh:

So I want to be mindful of the time, but I also want to ask, is it true that you wrote this entire book on your iPhone?

Hitchcock:

Yeah, I don’t have a laptop. And I was writing it at night, so it’s too noisy to have a typewriter. And at night, it’s too noisy to play guitar or have phone calls or anything. So mindful of other people. I would just be because I’m a fairly regular insomniac. So I would just be between the hours of 2:00 and 6:00 a.m. you know writing. And actually, I was trying to help me sleep, really, after I’d written a bunch of written a number of words, but it’s all on the iPhone, yeah.

Cavenagh:

That’s fantastic. I think it’s a great element to this for all the reasons that you said.

Hitchcock:

Well, it’s funny. You know I could be using an iPhone to listen to the music from all around the world if I streamed. As it is, I can still probably find it on YouTube. If I want to learn my old songs, I just go onto YouTube.

Cavenagh:

And watch yourself play them or watch somebody do a lesson?

Hitchcock:

No, I listen, I just find it, and then I can you know I don’t watch myself, but I re-familiarize myself with the chords or the tune or whatever because I actually only have a pool of about 50, 60 songs perhaps that I play, which is a lot. But there’s another couple of hundred lying around that I never play, so I can’t remember how they go.

Cavenagh:

Well, prolific, I think, is probably a great word to describe you, but also the understatement of the year, given your output over the last 45, 50 years.

Hitchcock:

Well, you know you have all eternity in which not to exist, so you really want to make the most of your time. And I don’t know. I mean, Dylan’s been pretty prolific. I mean, sometimes he doesn’t release anything, but then you find it’s all been recorded.

Cavenagh:

That’s like the Prince factor.

Hitchcock:

What do you mean? Because Prince was always churning stuff out.

Cavenagh:

Yeah. There’s a legend about Kevin Smith getting an interview at Paisley Park and them giving him the runaround for two days. And he wanted to see the vault because no one had ever been into the vault. But the rumor was that Prince had you know 500 I don’t know if he had 500 albums or 500 songs or…

Hitchcock:

Oh, yeah.

Cavenagh:

It’s just a lifetime’s worth of catalog backlog. So that’s why I refer to it like that.

Hitchcock:

Did he actually get to see them in the end?

Cavenagh:

You know what? I don’t remember the end of the story because I don’t think he ever made the documentary, so I don’t know that he ever actually got in to see the vault or hear it. But it’s worth a follow-up. I’ll have to look.

Hitchcock:

Whoa.

Cavenagh:

But one of the things that struck me, and this is a personal question more than anything, is I’m asking this in two parts. One of the things I’ve noticed listening to your catalog, I traveled to my parents over the weekend, and I had a lot of time in the car. So I listened to a lot of your back catalog on Spotify because it’s hard to play records in the car without them skipping.

Hitchcock:

Yeah, yeah.

Cavenagh:

But one recurring sound that I kept hearing, and I quite enjoy is the 12-string. And the 12-string is, to my mind, one of the most accessible sounds, but it’s also one of the most important sounds to psychedelia. And I’m wondering if you had, let’s just say not necessarily that it’s important to psychedelia as much as it’s prevalent.

Hitchcock:

Well, yeah. I mean, particularly the Byrds, particularly McGuinn, and how he and George Harrison echoed each other. But actually, I don’t play 12-string hardly at all. Where were you hearing it?

Cavenagh:

One of my favorite records is one of the Egyptians records, Globe of Frogs. And I spent a lot of time listening to that because I got it when it came out and listened to it.

Hitchcock:

Oh, right. Yeah. Yeah.

Courtesy of robynhitchcock.com

Cavenagh:

“Luminous Rose,” “Vibrating.” Obviously, “Balloon Man” has that crazy guitar so that was that Peter Buck on that?

Hitchcock:

No, that’s me.

Cavenagh:

That’s you playing that?

Hitchcock:

Okay. Yeah. There’s no 12 string, though. I mean, there would be I think I’ll tell you who plays Peter Buck is on. There’s two songs, and he’s playing 12-string on them. One of them is “Flesh Number One.” He’s very good at sort of picking up a melody inside a song. Those chords are already there, and he finds a sort of counter melody to go with it. It’s one of his strengths. And the other one he’s on is a song called “Chinese Bones.”

Cavenagh:

Oh, right, right.

Hitchcock:

He’s playing 12-string, but I’m not. I think I played a Telecaster.

Cavenagh:

Yeah. And I just misconstrued them. But I guess it’s leading me more to my question because you’ve worked with him a number of times, and you’ve worked with some other people over the years with some of your collaborations, which you’re as prolific a collaborator as you are a writer. And yeah, tell me about some of those. Obviously, one collaboration has gone very, very well with a particular member of the female gender (editor’s note: Rob is referring to Emma Swift – Robyn’s wife). But what can you tell me about some of those Pete Buck, Scott McCaughey kind of things that you’ve done in the last 15, 20 years?

Hitchcock:

Well, they’re all men of a certain age who we all listen to the same records. Sometimes they’re a little bit younger than me. And so a lot of the American guys, Peter, Scott, the late Bill Reiflin. I mean, they were backing me up for a while.

They were a great sort of garage rock band. A lot of those people used to sell our records in indie record stores around you know late ’70s, early ’80s. For some reason, you know The Soft Boys and my records seem to wind up over here rather than in British record shops. I guess they didn’t want them in Britain, but they seem to want them over here.

So a lot of yeah, those people just heard us. They were selling you know if you work in a record store, you go, “Oh, wow, what’s this what you did in the old days?” you know. There was no other way of hearing it. So they drop it on and they seem to like it. So a lot of those people were well disposed to me when I turned up. I met Peter and R.E.M. in ’84. I met Scott and the Young Fresh Fellows in ’86.

I didn’t meet Bill Reiflin until 2000 or so, but no, no. Earlier. Actually, it was only ’90s. But I did discover they’d all sold my stuff in shops, store record stores. But the other thing, I think, is that they’d all listen to Revolver. They’d all listen to “Mr.Tambourine Man” and “Eight Miles High,” and they’d all listen to Pet Sounds. Love. And they listened to Pet Sounds, which was not an influence on me. And they’d all listened to the Velvet Underground. You know they’d listen to those four extraordinary records and The Doors and Love and everybody in the stone. So we all had a common lexicon.

And there are people in Britain that have the same you know come from the same lake as it were. The most obvious one is Andy Partridge, who I did wind up doing stuff with writing a few songs from XTC, who was another you know child of psychedelia. He never took any drugs.

I mean, he couldn’t. He was not stable enough to take psychedelics, and he was aware of it. He’s got a very delicate mechanism, Andy. I really like him. He’s a good egg. But you know Captain Beefheart, The Beatles, Syd Barrett are all right up at the top of Andy’s record collection as they are mine. I think people like that– I just tend to meet more of them over here in the States than I do in Britain.

But I mean, most of them are also you know all nudging 70 or over the waterfall now. I do know some younger people. Davy Lane in Australia who is in a band called You Am I. Davy plays with me, plays acoustic and Mellotron on the album, the ’67 album. He’s a mere 43.

And a scampering pup. Yeah. But he’s on have you heard the ’67 album, which is the book?

Cavenagh:

No, I’ve heard the record. And that’s why I thought that campfire psychedelia is such an apt term.

C. Elliott Photography

Hitchcock:

Well, that’s David. I had a guitar. It was all done, I think, made me bar two songs where I had me and another guitarist. So Kimberly Rew from The Soft Boys, even older than me, was there for it was me, Kimberly and myself in Cambridge in Britain. And then it was Davy and myself in Sydney, Australia. And that was pretty much the whole thing. And then just a few little overdubs.

But no, Davey is a younger version of that same school that you know Peter Buck and Scott McCaughey and Bill and Andy Partridge and I’m sure many others, but you know the ones I’m involved with, those are the obvious ones. Yeah. He’s just a younger branch on that tree.

Cavenagh:

Right. No, I think that’s great. And you know you’re rattling off all those people that are the essence of my record collection. So it all make sense to me.

Hitchcock:

May I ask how old you are?

Cavenagh:

I am a youngish 56.

Hitchcock:

Oh, okay. So you’re sort of the generation after me. You would have been born in ’67, ’68.

Cavenagh:

Right.

Hitchcock:

Okay. So you wouldn’t have heard that stuff in real time. It would have got to you later.

Cavenagh:

Right. And I was lucky enough that I had a dad who not only grew up in England, but also listened to lots of folk. So he listened to Bob Dylan like a crazy person.

Hitchcock:

Oh, yeah.

Cavenagh:

And he listened to the Kingston Trio and Tom Rush, who’s an American guitarist.

Hitchcock:

Oh, yeah, yeah. He was on a link to that, yeah.

Cavenagh:

And my dad had a folk show on his college radio station and used to just play stuff. And he and I talk about it all the time. He taught me to play the guitar when I was a kid, but he can’t play anymore, so it’s frustrating for him. But you know he has this just kind of backlog of folk and that informed a lot of what I listened to. And of course, the Beatles and the Mamas and the Papas and you know there were a lot of bands in that kind of folk adjacent time that were my first exposure to music. But the Beatles, you know the Beatles were right in the middle of everything.

Hitchcock:

When was your dad born?

Cavenagh:

My dad was born in ’43.

Hitchcock:

Okay. So he’s exactly 10 years older than me. So was he a hippie?

Cavenagh:

No. No. He was a college guy and then an Army guy.

Hitchcock:

Oh, an army guy.

Cavenagh:

And then he became a college professor. So he kind of turned full circle. But you know his influence was you know a big part of what I started to listen to. And I, of course, stole all of his Beatles records and his Johnny Cash records. And that’s what you did.

Hitchcock:

Great. Oh, good. Good for him. Well, then he’d have been in that whole I mean, I looked up to people like that. You know I didn’t have an elder brother, so I mean, most of my elder brothers were fantasy elder brothers. They didn’t know they fulfilled that role to me. Obviously, particularly Bob Dylan, but you know yeah.

Cavenagh:

I love the nicknames everybody had, and I know that’s a thing, but the names everybody had in the book, you just get a picture of what they are and what they look like for good or bad. Oh, yeah. Well, that’s good. Some of them are names that some of those people are hybrids and some of them aren’t. But you know hopefully, it all blends together.

Cavenagh:

No, no. I get it, and I understand. But the combination of the book with the companion album, I think, is not only a fantastic concept, but the fact that you’re putting the songs in that you’re talking about, that you’re listening to that…

Hitchcock:

Yeah. Yeah. No, that’s really good. That was Emma’s idea. You know my wife, I mean, she runs the label. And you know it was clear that the book was going to come out. And she said, “Well, why don’t you just make a record to go with it?” you know. So it was all done fairly quickly. But they were songs that I’d known for three-quarters of my life. You know and often been singing, I’ve been singing. I sang “Waterloo Sunset” in my art school band back in ’72, ’73. So some of those songs are really older than me, really, just about there’s no Dylan, of course, because Dylan didn’t release anything in ’67 or not that we heard. So you know I mean, it was fun.

Cavenagh:

’67 when he was in the hospital after the motorcycle?

Hitchcock:

I don’t think he was in the hospital. I think he was just off the map. You know, at the time, there were rumors that he was in hospital because nobody knew if he’d been really badly hurt. And I think he probably exploited that to some extent. People would leave him alone. You know, but he was essentially when he recorded the Basement Tapes with The Band and John Wesley Harding. So it turned out that he was actually doing an awful lot of music. Arguably, it was his most prolific year. And then after that, I think that the fountain ran dry for quite a long time. But stuff was just pouring out of him or seemed to be. But we didn’t discover that until later.

Cavenagh:

Right. Well, I don’t want to take up much more of your time, but I do want to ask you another question or two if that’s okay.

Hitchcock:

Yeah, yeah, sure.

Cavenagh:

I guess it’s one of the most obvious ways to close an interview, which is to say, what’s next for Robyn Hitchcock? You know Is there another book? Is there another record? What’s next?

Hitchcock:

Well, Robyn Hitchcock is still here. He’s going to be very busy. I have a lot of old records here in the basement with me. I’ve got old master tapes that need to be baked and sometimes remixed if necessary. I’m working on getting the rights back to some of the records that were on major labels. I love playing live, so I will continue to play live, but probably less than I have been doing or traveling less.

I’m working on more book writing kind of thing. But I don’t know. I won’t say anything more until I finish it, but there is definitely something in the works. And hopefully, I’ll find a publisher. And I’m drawing. I always draw. And I’m actually halfway through a batch of paintings, I had to stop for a while, but I’m hoping to finish those off after all you know next year.

So masses. It stretches off to infinity, Rob. I mean, I have enough work to last many lifetimes. Sadly, I’ll only be able to complete this one. But if I am cloned and put into an as seems highly likely, if I become a phone, which is what’s going to happen to us all in the next few years as we merge with our phones, and there’s a sort of AI version of me which is constantly updating and self-regenerating and intends to be much better than the original. I hope my AI avatar is able to carry on with what I’ve begun you know.

Cavenagh:

I would have thought it would have been a trout.

Hitchcock:

Oh, it might be. It might be a digital trout. I mean, there’s no reason why these things shouldn’t be shapeshifters.

Cavenagh:

I always like the end of that song.

Hitchcock:

Oh, “Devil Mask.” Next time round I’ll be a trout. Yeah. See?

Cavenagh:

Oh, well, yeah. Let’s hope it’s a lucky trout. Well, I, for one, I’m looking forward to seeing you. I think you’re coming through the New York area this fall, correct? Yeah. Where are you?

Cavenagh:

I’m in Soho right now.

Hitchcock:

Oh, okay. Well, then, no, we are totally. We’re going to be in fact, I’m doing a book session on the first (of August) at Rough Trade. Oh, with wherever it is. You know It’s the Brooklyn, I think. It’s with David Fricke. You have to check the websites, but it’s August the 1st. I’m doing one of those. And I’ve got a gig on October 30th, I think, at City Winery.

Cavenagh:

Oh, good.

Hitchcock:

You know I love to come to New York, so I’m sure I’ll always be I’m sure I’ll be as long as I’m visible, it’s one of the places I’ll be visible.

Cavenagh:

Good. And you’re currently in Nashville, correct?

Hitchcock:

Yes. Yeah. I’m in Nashville, but I’m often in London and I’ve had a lot of time in Australia recently, so you know I flicker.

Cavenagh:

Well, that sounds good. Well, I’m glad you’re able to get around and do what you do. We’re all the better for it.

Hitchcock:

Well, thank you very much, Rob. That’s absolutely great. What would you reincarnate as if you had the chance?

Cavenagh:

I think a hummingbird.

Hitchcock:

Oh, beautiful. And they don’t last that long, so you could probably be a chain of hummingbirds.

Cavenagh:

Yeah. My wife and I are obsessed with hummingbirds if you liked it.

Hitchcock:

Oh, God, they’re beautiful things. I don’t know if you get many of them in New York.

Cavenagh:

We do. I live north of the city, and we have hummingbird feeders in the front and back of our house, and we’ve been going through sugar water like it’s going out of style.

Hitchcock:

Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. Oh, wow. Oh, is that what they like?

Cavenagh:

Yeah, they do. It’s kind of like simple syrup.

Hitchcock:

Okay. Yeah. I should try that sometime. I just have to be in one place long enough to attract a hummingbird.

Cavenagh:

The trick is to not make it too sweet because then you attract bees. So it’s a delicate balance.

Hitchcock:

Oh, man. Well, actually, there’s been a shortage of bees, I think. There’s a lot of dark black bees wandering around at the moment. I think they’re not bees, but they’re so big, I can see them without my spectacles. That sounds fantastic.

Well, that’s really good. Oh God, I’ve got to get going. I’m so glad we managed to chat – tell Rachel, I’m sure you will, that we’ve managed to speak. And I’ll see you up there somewhere.

Cavenagh:

I’m looking forward to it. Thank you so much. Appreciate the time.

Hitchcock:

You’re very welcome, Rob. All right. Take care.

Cavenagh:

Talk soon.

Hitchcock:

Cheers. Bye.

Gallery

Recent Articles

Immer Für Immer by Flying Moon in Space–Album Review

•

February 13, 2026

Vinyl Relics: Fields by Fields

•

February 10, 2026

Loading...

Vinyl Relics: Would You Believe with Billy Nicholls

- Farmer John