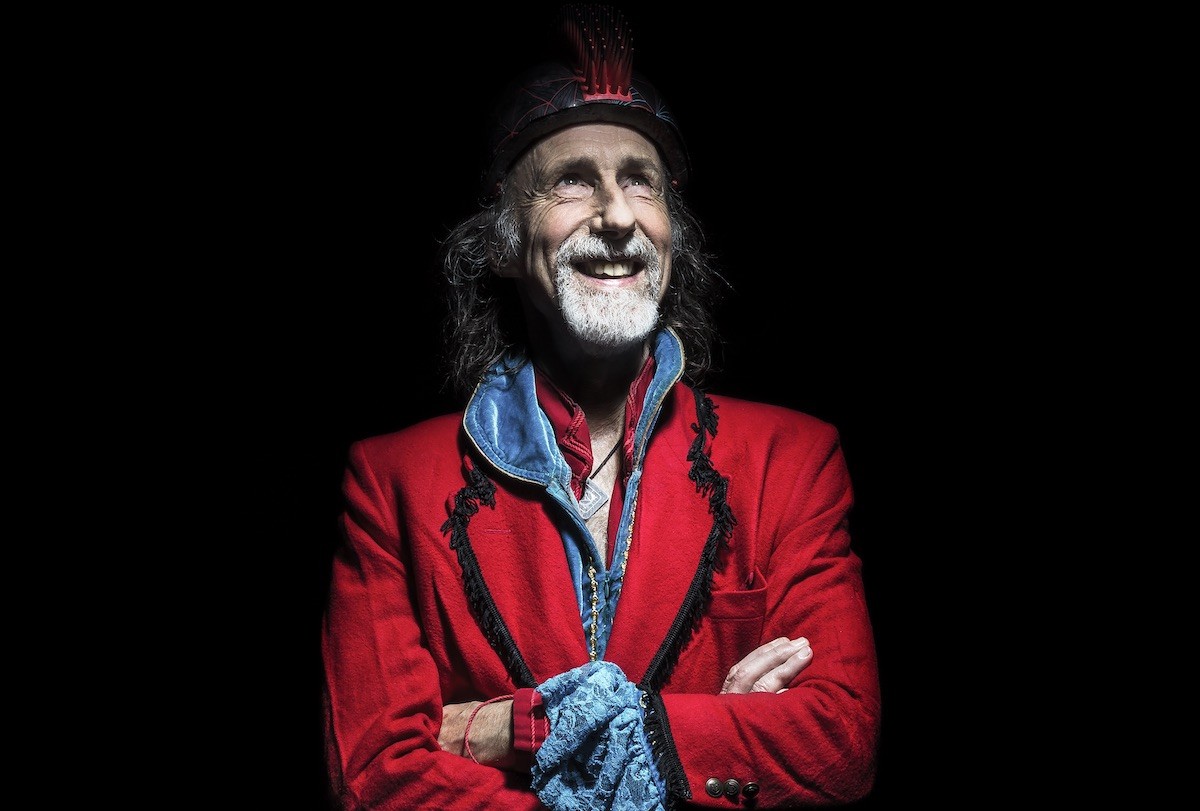

New Interview with The God of Hellfire, Arthur Brown

New Interview with The God of Hellfire, Arthur Brown

Psychedelic Scene: It’s been almost a year since I last spoke to you. What have you been up to in the past year?

Arthur Brown: Well, we’ve been dealing partly with the new album that’s about to come out on Prophecy.

Okay.

And also their 25th anniversary concert that they just had a few weeks ago in a cave in the Balve, a fantastic location. It was all the artists from their label, and it’s a lot of doomers and heavy, dark metal, but really lovely, lovely festival. Indeed.

The album that you’re talking about is coming out under what moniker?

It comes out under Prophecy. It’s just called The Long Long Road.

Okay. And is this an Arthur Brown record?

It is. Yeah.

Have things opened up in London? Is the pandemic pretty much under control there?

Well, as much as it’s under control anywhere. Really, after two years, you just admit there is scientific evidence this way and scientific evidence that way. Nobody knows still why it came out, how it came out. And as to what the full intention is regarding it, it’s impossible to say at the moment they tried to stop downs. Of course, the economy starts to go down, so you can’t do that for too long. And so they basically left it up to the individual citizens to do what they felt was right in that situation. And of course, there were certain things they asked everybody to do, like wearing masks in certain places.

It sounds very similar to how it is here.

Yeah. I think it’s the same everywhere. Very strange time and a lot of soul searching going on when things are not clear and definite and one answer for it, then the soul searching starts.

I didn’t know whether I wanted to form a band or go and live in this Tibetan monastery in Scotland.

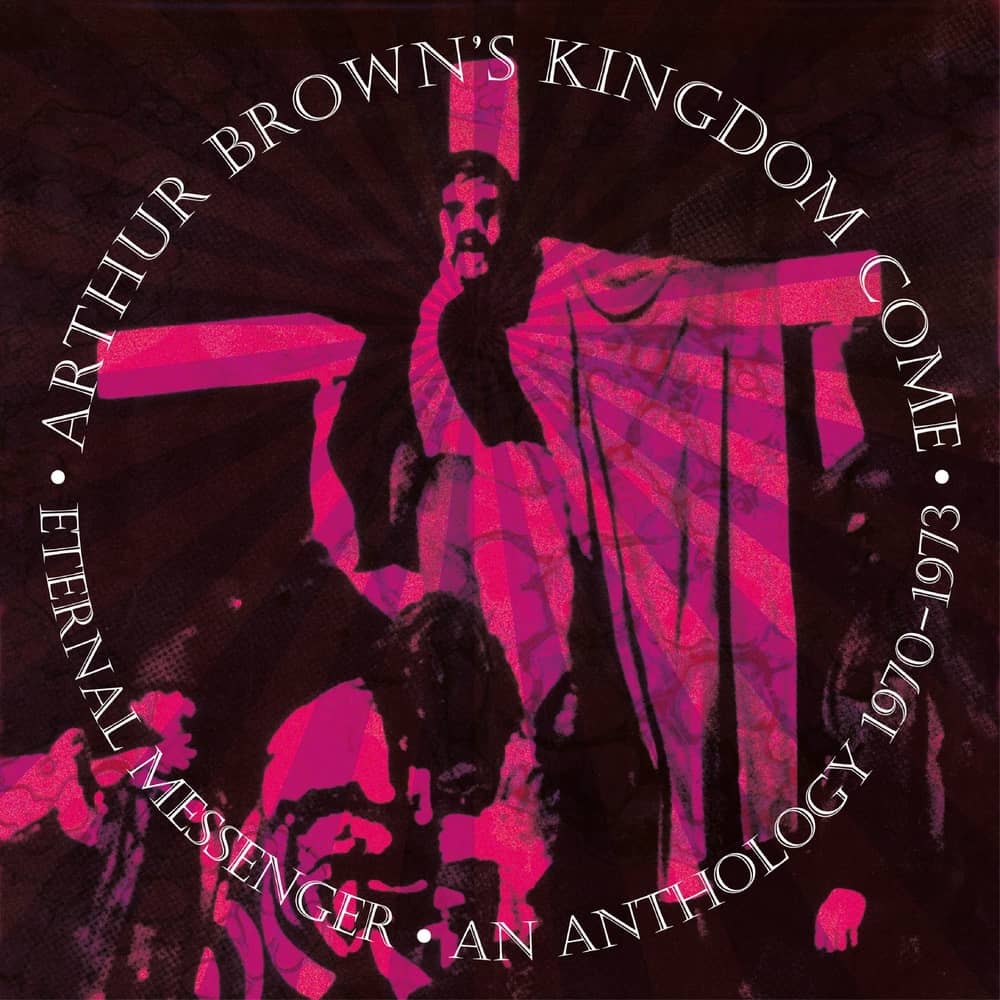

I noticed that there’s a new compilation album out called Eternal Messenger, which covers your early 70s output with Kingdom Come. Was that something that you had been wanting to get out there?

Yeah. It’s done through my basic back catalog is with Cherry Red Records. And so they have another company that they fund, like we call Esoteric, who’s been putting out good music for a long time. And so it’s come out basically on Cherry Red, but through Esoteric, Mark Powell.

And it’s three albums made by Kingdom Come. There’s the album that covers the getting together of the musicians and jamming and doing and all that and finding the ones that we’re going to actually play on the record. And then another album of BBC tapes and a good piece of writing by Malcolm Dunn. It’s very good indeed. You open your own box heads with some trepidation thinking “Uhh”, but actually, I was very happy with it and so was Claire. It’s well put together very good on the history.

So it’s everything that band ever released?

Yes. I think it’s everything. We may find a few pieces that we didn’t come across this time, but basically.

I noticed that there’s a re-recording of Fire with Brian Auger, James Williamson of The Stooges and Carmine of Peace from Vanilla Fudge, who I just interviewed a few months ago. How did that come about?

Well, as I say, I’ve signed a deal with Prophecy for it’ll take me through about another two years.

But, there was included in that deal, the ability to make this album with Cleopatra. They were last year 1950s horror tunes, but it’s sort of fun when it’s done their way. The older tunes are spoofs, really. But this involved a lot of great musicians. Each track is different. There are one, two, three

people who produced it in layers, and it probably got about 20 well-known musicians on it.

You’re talking about an album?

Yeah.

You’re talking about the re-recording of Fire on a particular new album?

As far as I know, that is coming out on that album, it’s certainly joined to it in spirit, and it’s put together in the same way. So that one was done basically as the part of the soundtrack of one of those B-grade horror movies on a rainy day. You put it on and half watch it.

Okay.

Some of my favorite people there. Brian Auger was always someone I wanted to play with.

Carmine Appice and I were going to put something together in about 1985, I think it was. The other people are also sort of monsters in their field, so it’s quite an interesting way to put an album together.

You must have some association with Vanilla Fudge since you worked with Mark Stein not long ago, too.

Yeah. Well, of course, we were playing festivals right about the same time as Vanilla Fudge, and we’ve also played with them over the last ten years, quite often on the same festivals in Germany.

You mentioned festivals recently, and I wanted to ask you about something I read not long ago. You would occasionally shed your clothes back in the old days. You were even arrested for it at a festival in 1970. So what was going through your head at the time?

Of course, the body is a beautiful thing. It’s a great sketch somewhere by Dave Allen, who says, Imagine if God in the Bible, in that addition, says, because of this wicked thing you’ve got here (motions to crotch), you’re going to suffer. Well, he said, Why did you pick that threat? If you had his nose, then everybody would have to wear sort of underwear over the nose and the rest of them would be naked. And it was just sort of a way of saying, “Well, The body is a beautiful thing”.

There’s no shame in nudity.

I don’t bother doing it nowadays.

Yeah. It seems to be more of a thing to do when you’re younger.

Yeah. Although I’ve known communities where a lot of them are older.

And, by that time, it’s no different than people wearing clothes. It’s like part of the daily thing now, like that.

So I wanted to ask about the formation of Kingdom Come. I think the Crazy World of Arthur Brown broke up in ‘69. Did you ever consider just continuing with that same band name just because you were the focal point of the band?

Not really. Because at that time, I considered Vincent and Carl Palmer had gone off and formed Atomic Rooster, and that was a successful band. I just thought, “Well, I’ve moved on as a person, so I’d like to write new stuff”. It was a strange thing, really, because I didn’t know whether I wanted to form a band or go and live in this Tibetan monastery in Scotland.

And I went out into the meadow of the place that I was living.

And I saw an angel. What resulted from that was that definitely the way for me is I’m going to form a band. And that’s what I did. And that meant putting together a group of people.

So then who joined the band?

Well, you see, it was a process, first of all, before deciding that it all had to be new. I went into the studio and I did a recording with some people that just came together.

The occasioning of that was that Drachen Theaker, who was the drummer of The Crazy World before Carl Palmer, and, who you might say, spiked with some wicked substances. And in the end, he had to leave. And so move on. A year and a half, he came back to England in the meantime, having and played with Arthur Lee of Love, Graham Bonnet and various other people. So he had a good time while he was not with me at all. But then we decided we’d just get some people together and see what came out in the studio.

And Giorgio Gomelski, who was the proprietor of Marmalade Records, where Julie Driscoll and Brian Auger were, and who was a very influential figure in English rock history. He was the one who did The Yardbirds, for instance. That was Giorgio Gomelski’s doing, so he had been in at the beginning of the experimental music that led into the 60s. He heard it and said, I’ll put together a tour in France for you. So we went and did the tour in France. And I did call that one with The Crazy World because all the music was a bit different.

We did for the sake of the tour– so that the audience would recognize at least one thing–“Fire”. The tour resulted from the Communist Party in France had had to deal with the situation of the revolution over there. And so they were putting these tourists on to show that the youth was now not wanting to be in revolution. So they had the Pink Floyd, the Soft Machine, ourselves, and I can’t remember who the fourth, it was four bands– not playing on the same night, just separate tours.

That was one of the occasions where I did take off my clothes. And this woman, this old lady who was about 60 was sitting next to Georgio Gamowski. And when I came out in that nude state, she fell. So Georgio said, “All you alright?” “Oh, yes. Now I have seen two naked men in my life, first my husband, and now this man.” And so at that point.

I had meetings with the heads of the Communist Party and slightly changed the act. And I didn’t come on naked anymore.

Okay.

We have already lost one seat in the government as a result of this and so, we would ask you not to.

What do you mean, you lost one seat in the government?

They did– the Communist Party. Local elections at that time. And this was enough to dissuade some people from the Communist government.

Wow.

And so they asked, look, the elections are still going on. Please.

If it is a moral, absolute, moral decree in your heart that you must do this, then do it. But please, we are asking you and I thought, Well, they’re the ones who put this tour together. They are trying to do something of some value. I’m just not doing it.

I got up at about 5:30, drove to the studio, strode forward, and delivered a big scream.

So I went to Germany with my new manager then and met the head of German Polydor and played them this tape that we just put together. And the boss at that time said, “You’ve done it once before, you can do it again. So here’s the deal” and gave us a three album deal, one a year. And there was enough money from that to rent a warehouse in Covent Garden in London. And we decked it out with sound equipment and lighting.

From there went through a series of musicians. We had, for instance, the first drummer was called Andy McCulloch, and he just came from King Crimson. That was the Larks’ Tongues in Aspic album, I think I’m correct. And we had various musicians. And over a period of four months, we wrote all the songs and we made the stage act. We got it all and put in the imagery, the crucifixions on the cross. The guitarist was a telephone which would ring during the act, and I would pick up the phone and I would talk to him and his voice would come out of the phone and we’d be talking and singing. And so various things like that came about for some of the time. We had for about some months after that, Dave Ambrose, the bass player with Brian Auger, played in the event. But we came out of that whole thing with the first album, The Galactic Zoo Dossier.

So that’s the formation of Arthur Brown’s Kingdom Come?

Yeah.

I wanted to ask you. You just touched on the religious imagery. I’m not religious at all. I’ve never read the Bible, but I recognize Kingdom Come as something biblical.

It is. But it was also a reference to having gone away with and been in America for about six months. And coming with a new band that was doing new material by then in Kingdom Kome. We didn’t do Fire or any of the Fire material, so we had to create a whole new audience.

Well, people certainly knew your name, and I assume they knew that you were very theatrical.

Yes.

So they had some idea what to expect.

They did. But it was a different kind of music.

We lost three quarters of the audience who didn’t like the new kind of music. But we built it up again to where there was a good audience.

Was there, like, a religious theme to the band?

Not as such. No. Although the title, Kingdom Come is the name of the band, and it is a religious statement as such. It was like coming back to England from America, having separated from Carl and Vince and then thinking. “Well. That’s quite a long time”. But by the time I got the band together, as far as doing concerts in England, it was probably about a year, a year and a half. And in those days, that was a long time to not be playing.

That was one of the occasions where I did take off my clothes.

Right.

And so I remember being down in Glastonbury with the bass player, Dennis Taylor. And he said, “Well, if you’re going to form a new band, what’s going to be the title of it?” It’s almost like I come back here. I started doing all the theatrical rock, and now I left it behind.

So I’m coming back. I almost like to claim what I created, my Kingdom, my theatrical Kingdom. So I said, I’ll call it Kingdom. And then Dennis said, “Well, if you’re going to call it Kingdom, you might as well call it Kingdom Come”. It’s something that is lodged in some people’s mind. And of course, it does deal with some spiritual things.

Right. So it sounds like it had a double meaning.

Yeah. Also, the side of music at that time where you might get ripped off by the company representing you financially. My manager said he thought that was a bit like a crucifixion and the stage act kind of in part. And it was also to do with if you had certain beliefs about society and stuff. There was a period where the government didn’t like that. And so there was a feeling of crucifixion. There’s a lot of the people in that movement, the Underground, and particularly the leader of it ended up in jail for seven years until the whole underground thing became less than it was.

And so the theme of crucifixion was in there.

In your stage show?

In some of the lyrics.

Yeah.

In some of the lyrics on the stage show. Whether you believe in one religion or another, that’s up to everybody. Like you said, you don’t believe that.

Well, yeah. I just wanted to get some clarification about whether there were religious overtones to that band.

What it partly evolved from was that, of course, as you say, the band broke up in America. I was over there when Bobby Kennedy departed from the planet. Various other people were killed, of course. And the pictures of the Vietnam War direct from the battlefield started to appear for a short while on TV itself. It was so shocking in those days because it wasn’t the kind of thing that appeared on a news program at all. So, the idea that the peace marches, the ideas for how to live in a different way, looking after nature, all of those things that were part of the Underground. There were other people who believed in them who weren’t part of the Underground. But they were there as almost the core of the Underground. Those things clashed. And do you know, the Kent State riot was where it crashed most evidently. So those things had been milling round in my mind. I came back to England, which was not in the same state as America, but had some of the same things going on, which led into Reagan and Thatcher and all the massive changes in social structure and stuff.

One of the ways that some of the people living in the underground was a kind of spiritual vision. And it underlay the idea that a human being is creative, is exploratory, and that society itself should be made in that form. They were stamped on. And so part of the album reflects all that. But behind it was this kind of spiritual vision.

And you’re referring to Galactic Zoo Dossier?

Yeah.

Well, you played a role in the movie Tommy as a priest, coincidentally. I didn’t know that when I talked to you previously. Did you have to audition for that or did you just get that on the basis of your theatrical background and knowing Pete Townshend and so forth?

Well, when I met Pete, I was dealing with the Fire theme. He was dealing with something that I think was around them. And it was called Rayal, and it was about China, and it had a theatrical lead player. So initially, I was supposed to be Tommy. And then Kit Lambert and I separated, left the management and everything, and he felt that whereas Pete was thinking of a lead solo singer, he said, “No, we’ve got to keep it for the band. Keep it for the band!”

We’ve got Roger is the lead figure, Pete. And then we got all these other people playing different parts, Jack Nicholson and all the other people. At one time, Pete wanted me to do the priest, but then it became the case that the finance for the movie was got through Robert Stigwood. And he, of course, managed Eric Clapton. And so it came about that Clapton was the preacher in the Marilyn Monroe scene, but after he did some part of it, he didn’t do the whole of the song.

And so I was called in and had the pleasure of working with Ken Russell. And he’s quite a character. And so that’s how I sing the part of the priest.

Okay. So you replaced Eric Clapton, basically?

Well, yeah, he did some of it, and then I took over from it.

Oh, I see.

Because he did the first half, really. And he was the preacher. And then for some reason, he didn’t do the rest. And of course, he’d had a beard, which I had. So there wasn’t too much of a visual discontinuity there.

You were playing the same character that he played?

Yeah.

Oh, I didn’t realize that.

Well, it was the same song, and he came into the grotto as in his priest garb. And then it does the scene right in front of Marilyn Monroe. And then that’s me.

Okay. You recorded with the Alan Parsons project. What year was that? And what was the song?

I think that there was ‘76, and it was The Telltale Heart from the first Alan Parson’s album, Tales of Mystery and Imagination.

Okay. Yeah. That’s the one that has all the Edgar Allen Poe stuff on it.

Yes. Alan. I think that was the first time I’ve met him. And so I got in there and he put on the track, and I did it in, I think it was second take. But then I got a call saying, “we need you to come in tomorrow morning at 8:30 in the morning”. “What do you want me to do?” “At the end there, we didn’t quite get the big scream in its entirety. So we would like you to do another big scream”.

I got up at about 5:30, drove to the studio, strode forward, delivered a big scream. And that was what appeared on the album. Yeah, it worked.

Great! Wow. That’s a lot of effort for a scream.

Yeah. Well, you know, those filming people, they’re so extravagant.

Yes. I’ve noticed that your music is sometimes described as psychedelic soul, like on AllMusic.com. I don’t know if you’ve seen that, but I found that kind of interesting and a little bit perplexing, too, because you seem like a rock artist to me. Not that you’re singing isn’t soulful; it is. But there are other artists that are rock artists who haven’t had that label applied to them. I know you did “I Put a Spell on You”, and I think your song “Sunrise” is very soulful. How do you think that you got labeled with that term “psychedelic soul”?

Well, because I started in music in a trad jazz band, playing bass and then started singing, then took classical stuff, then joined a mod band, and we were doing various things. And it was during that period that James Brown did “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag”, “It’s a Man’s World”. All of that came out. And so it was part of the sets that we used to do because during that period was also a member of The Ramong Sound, who at the time I left, changed their name to The Foundations and had all those hits. Do you know The Foundations? (sings: “Baby, Now That I Found You”)

I know that song.

Brown: and “Build me up, Buttercup”.

Oh, yeah. Okay. I know The Foundations.

Then the basis of their music was some R n’ B in the modern way, but also soul. So we do a lot of Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett. So I did. I sang a lot of soul, and I loved it. I thought it was great music. When The Crazy World started, we also did some of the sole pieces and some Nina Simone. She was jazz, blues, and soul. So I think that’s why it was a style that I had absorbed and loved. And I sang a lot of it before and during the beginning of The Crazy World.

I see. I also read that you moved to Africa in 1979. What inspired you to do that?

I wanted to go and find the real people who knew the meaning of the African dances. So I went to Burundi and for about five… Maybe a week I was leader of the Burundi Orchestra, which turned out to be, of course, that I’d forgotten the French word Orchestra is banned. And so it was about a ten piece soul band, which was doing funk and soul. I also did some teaching there of the history of music and how the Western ballad forms and musical forms for folk came together with the African rhythms.

And in Burundi, they play this thing that looks a bit like a wooden tea tray with round ends and one string is all the way. And so the strings longer in the middle and shorter at each end. And then you play it with your thumbs. And it’s quite an amazing instrument. And that later Adam and the Ants used their music form. That was what they based their music on.

Oh, okay. I think I know what you’re talking about. I can hear it in one of their songs. Like, “Goody Two Shoes”. Is it used in that?

Brown: I think it was that one. And they called it the Burundi Beat. It wasn’t at that time I had great fun bringing in traditional musicians, saying to the class, “Listen to Howlin’ Wolf. Now listen to this”. And exactly the same rhythm from the tribe. And so you’ve got an idea that some people came from a different country with their own folk rhythms joined into what became rock and roll. And that’s how the music developed because I had a lot of African students in the class as well as European. And they all thought at that time the Rolling Stones music and all that that’s Western. And if I asked them who made it, they would sell the Western people. And I said, “Well, just listen to this. No, it’s a blending of the two musics”. So I find that kind of quite exciting as an exploration for myself.

How long were you in Africa?

Brown: Between six months and a year.

Okay. I also saw that you moved to Austin, Texas, in the US at one point.

Yeah. I was there for a long time, over ten years. Of course, when I got there, which was about ‘81, ‘82, if you went to 6th street in that time, Austin was not built up like New York or anything. Now it’s getting much more like a big city. It was like an outback. But along this one street, 6th street in, say, about 42 houses or properties. Some of them were bigger than houses. Different style of music.

All live. Every building. And then there was the big one, the Armadillo. And you had all kinds of people. Willie Nelson was already there on his ranch, and then Stevie Ray Vaughn didn’t come until later.

Yeah, and there were a lot of the older blues guys who came there. There was one who was 92, and he arrived there. He was called Grey Ghost because he was one of the guys who just traveled endlessly, playing in whatever establishment his keyboard player and singer. And then he would be put up, lodged by that early in the morning or late at night. If you got there in the afternoon and slept after the gig, he would just suddenly disappear. And he would jump on a train. A train jumper. No ticket.

Even at 92?

Yeah. And he ended up in a railway car on a plot of land. And people used to come. And it was only about, say, 40 people in the night would come and see him. But it was always full.

Well, Austin is, of course, known as the live music capital of the world. Were you, like, a part of that music scene there for the duration of your time there?

Yeah. I had a bad for some time there with Jimmy Carl Black of the Mothers of Invention. I had a different band in which the guitarist was from the underground band of the 60s, Spirit.

John Stahili, and his brother was a lawyer, and he was the bass player from Spirit. So they both lived in Austin. And we had a band together. I didn’t do any touring.

Did you perform live with local musicians and so forth while you were there?

Yeah. But not, like, constantly. Just now and again, I was more concentrating on the…I went into construction, but in my case, it was like carpentry and house painting. And that was my focus for that period.

All right. Well, what’s next for you?

Well, you mentioned soul music. Coming up in about ten days is a concert of soul classics that I’m doing down in the Pizza Express, which has got a room. It’s quite small. It’s about 120 people. But the amount of great musicians that play there, it’s become a very important place.

An unlikely place.

An unlikely place, indeed. But I think their theme was, well, we get a flow of people through here eating. We can increase the flow and then make it sort of like the old jazz diner. And some people love to play there.

In November/December, I’ve got about four concerts with the Hamburg Blues Band that’s been delighting the blues audiences, the R n’ B audiences in Germany for about 25 years, and I’ve been singing with them. I like singing that stuff and also sings Chris Farlowe.

Who’s that?

Chris Farlowe. Let me see. At the time when Otis Redding was singing, he was one of the few people that Otis Redding invited to sing with him…from the English singers.

Oh, yeah?

Yeah. He had about three hits and one of them was written for him by The Rolling Stones and he also sang with Colosseum.

With who?

Colosseum. It was jazz-rock.

Okay.

He was one of the great early singers in the Flamingo Club.

All right.

Where Georgie Fame became famous. So he sings Maggie Bell, who was one of the great rock singers in England from about 1970 onwards and then various other people in that style of music.

These are people you’re going to be working with in the near future?

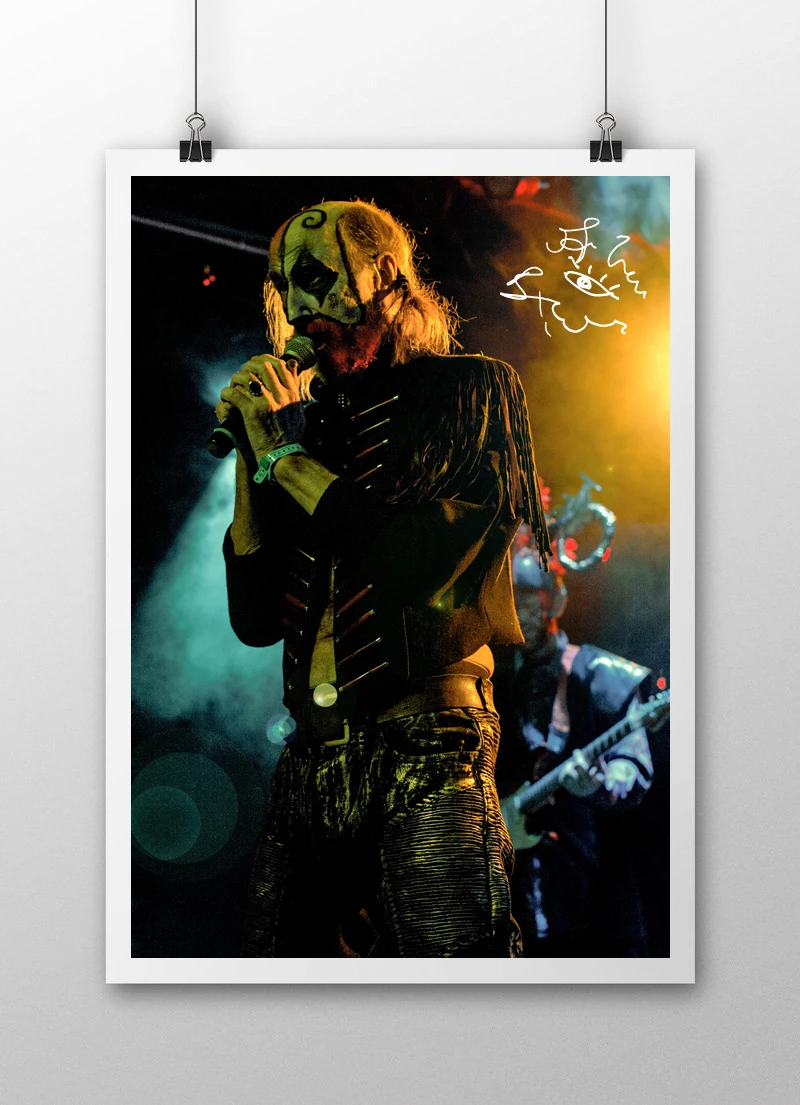

Well, I do evenings with them. And so there’s four of those between now and I think December the 17th. But also, we’ve got the Crazy World Tour, the modern Crazy World band, the present one, which is a multimedia piece. It’s a show, and it has incredible lights and projections and theater.

We’ll take songs from all the way through my career and then some new material as well.

And we’ve played that out about six times so far, and the reception has been amazing. So we’ve got a tour in England in May, June. Coming up.

Great! All right.

Claire is the creative director of this show has been concerned with the building of all the visual images and how the interface between the music and the lights and the visual imagery. We’re looking at a great visual guy, Andy Clark, who before that one of his major things was doing the visuals for Yes. And he’s just an incredibly creative person.

And the musicians, two of them were with an experimental album that registered quite strongly in Europe. And then the keyboard player, he had two recent bands: Heliocentrics and The Noisettes.

He had a few hits in England recently.

He is quite amazing. And then the bass player is Jim Mortimer, who I played with for about ten years on and off, and the drummer is Sam Walker.

And this is the current touring version of The Crazy World?

Yes, indeed. It has experimental electronic overtones. So it is a really a dramatic whole thing to show.

I wish I could see it.

We are currently looking at agency for playing across the world.

That’d be great.

It would.

Well, it’s great that you’re doing all these things. You’re so busy.

Yeah. With the soul evening, I’ve had to learn a lot of new tunes. It keeps me awake.

Yeah, well, great. Thanks so much for talking with me again. It’s been a pleasure.

Always.

Related: Interview with Arthur Brown

The Top 100 Psychedelic Rock Artists of All Time

The 100 Best Psychedelic Rock Albums of the Golden Era

The Top 200 Psychedelic Songs of the Original Psychedelic Era

Gallery

Recent Articles

The Circle is Red by White Noise Sound–Album Review

•

March 2, 2026

The Best Way to Do MDMA-Assisted Therapy

•

February 27, 2026

Loading...