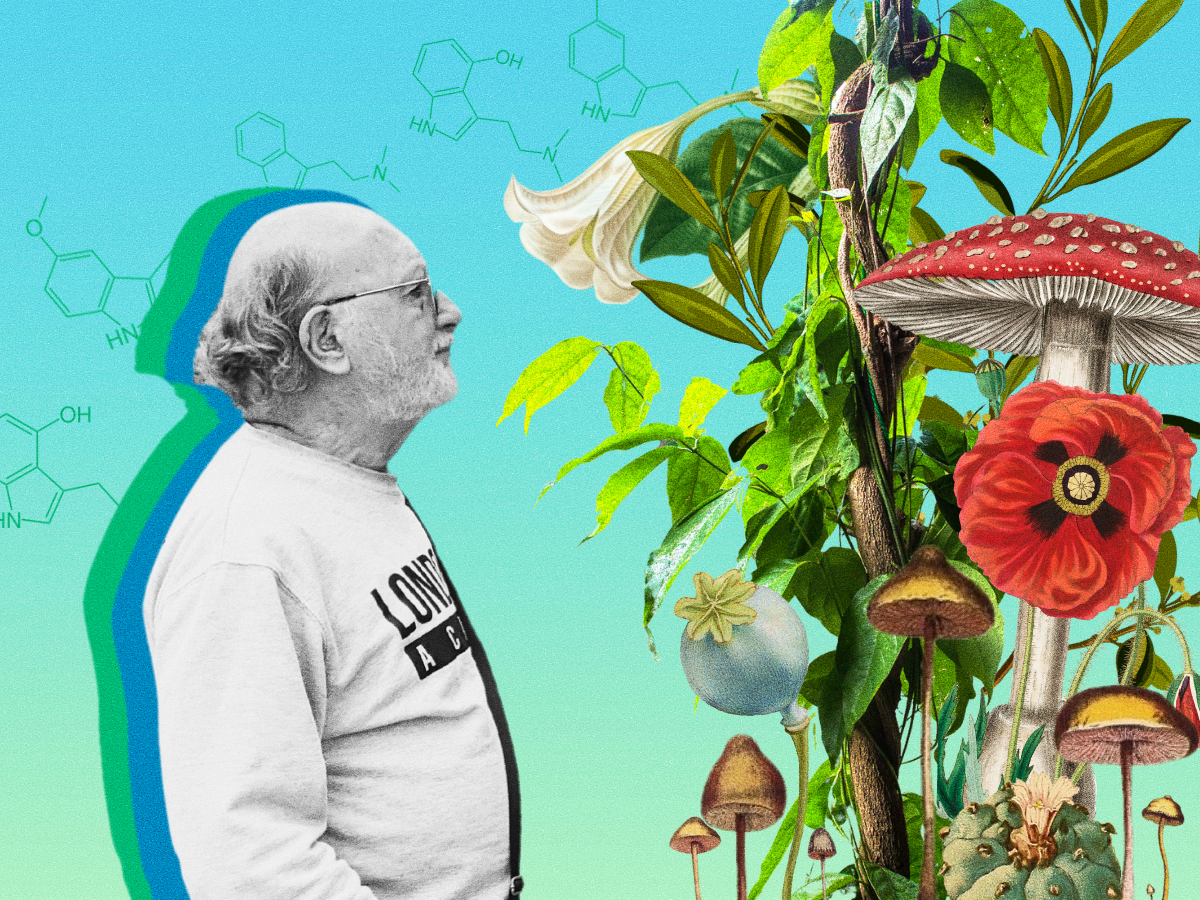

Interview: Dennis McKenna

Interview: Dennis McKenna

Brian Taraz:

Hi, I’m Brian for Psychedelic Scene Magazine and I have the great honor on this day, June something or other 5th, 6th, 7th. There’s fires burning over Quebec smoking up New York City. But on the West coast in British Columbia and then here in Tucson, Arizona, I’m having a chance to speak with the right honorable Dr. Dennis McKenna. And hi, Dennis! How are you there?

Dennis McKenna:

Good to see you. Nice to be here, Brian. Thank you for inviting me.

Taraz:

A pleasure. So because Psychedelic Scene is a culture and arts magazine and not necessarily a science magazine or so forth, you can look up Dennis McKenna and the McKenna Academy, you can look up ESPD, is that right?

McKenna:

55, ESPD 55. Visit the website at ESPD55.com and all of the content is open. You have to register with your email, but then you could look at all the videos and everything else. So it’s open access. We’ll just steal your email there.

Taraz:

Oh nice, stealing the email. If you’re a psychedelic oriented person, we don’t need to rehash the credentials of Dr. McKenna: a great promoter of Pablo Amaringo and visionary ayahuascan art. Is that accurate?

McKenna:

That’s correct, yes.

Taraz:

And great care and concern for trying to allow western adoption of valuable vegetable medicines from the Amazonian area, as well as trying to protect and interface with the people there to preserve their cultures and the environments through all the work he does with the McKenna Academy. And the Heffter is the name of the place, right. Your scientific institute?

McKenna:

Heffter Research Institute.

Taraz:

That’s Heffter Research Institute.

McKenna:

That’s much older. I’m a founding board member of that. I think the founding year was 1992 and it’s oriented toward research. It really has nothing to do with the McKenna Academy. They’re not the same. But the Heffter Research Institute, which you can go to at Heffter.org, and see what they’re doing. They’re very much oriented toward research. And basically, it was an organization founded back in the 90s, around 1992 by a bunch of nerds. Essentially at that time, we were clinicians and I was the ethnopharmacologist or ethnobotanist. There were chemists, there were psychiatrists, there was a mixed bunch, but basically scientifically, medically oriented people that wanted to find a path forward that recognized that psychedelics were valuable therapeutically and wanted to find a path forward to make them legitimate, to bring them into the mainstream. Well, at that time those were dark days. If you think back to those times, psychedelics, now everybody’s talking about it, it’s on the tip of everyone’s tongue. Back in those days if you were into psychedelics, you didn’t talk about it to everybody because it was illegal. And also there was a tendency to say, oh well, my focus, my passion in life is psychedelics.

McKenna:

At that point back then people would say, oh, I have an appointment coming up, I have to go, sorry. They just try to get away from you as quick as possible because they identify you as a nutcase. Well, our ambitions to bring psychedelics into the mainstream have succeeded beyond our wildest hopes and we’re not taking credit for this. I think that everybody in the psychedelic world is as astonished as we are at the changes that have taken place just in the last ten years or five years. I don’t think we ever imagined when we had the Heffter Institute. We used to fantasize about, well, one day we’ll have a center for research where people could come and get these therapies and that was our vision. And in some ways, this was too small a vision because now there are centers of research all over the world. It’s found its way into academics and so there are all kinds of centers for psychedelic research at legitimate institutions. And that’s great, I think that’s wonderful because I do believe in psychedelics and I think that they are a few things well… Therapeutically they have great promise and as tools for understanding consciousness and exploring consciousness, they also have great promise.

McKenna:

You don’t have to be sick in order to benefit from a psychedelic. Curiosity alone is an asset but psychedelics give you a means to sort of look beyond your reference frame. In some ways that’s the whole point that they let you step out of this reference frame which neuroscience now calls the Default Mode Network, I prefer to call it the reality hallucination. It helps you step outside that reality hallucination that you construct for yourself. Everyone does. To live, just to be able to live and do ordinary states of consciousness most of the time that’s useful, but sometimes you need to step outside of that. And I really think that’s a lot of what psychedelics, that’s a lot of their benefit therapeutically is that they let you step, in a way, step away from your own reference frame and look at situations, issues you may have maybe with trauma or addiction or depression or whatever it might be. The whole litany of things they talk about that psychedelics can be used to treat. What they all have in common is this ability to step away from your habitual reference frame and look at things in a new perspective and that gives you the ability in some ways to kind of diffuse these things that become obsessions that take over our lives.

McKenna:

And I really think that’s a lot of what the therapeutic use of psychedelics is. That’s the therapeutic mechanism in a broad sense. That’s what psychedelics can do.

Taraz:

You started with Heffter as an early scientific framework to pursue psychedelics, find out what’s the chemical construct, how it interacts, and join with academic institutions and now at this point it’s blown up. Paul Stamets here, all these doctors, Johns Hopkins doing therapies, and so forth. How do you feel it’s being unfolded?

McKenna:

Well, I should say Paul Stamets is an exception. Paul Stamets has his own path.

Taraz:

That’s true.

McKenna:

He never got support from the Heffter Institute, but most of the early clinical studies with psilocybin, including Johns Hopkins, were funded through support that the Heffter Institute got really to support that research. Roland Griffiths is on our board, and he wasn’t the first one, but he is now. The Heffter is much quieter and not as well known as MAPS, and MAPS is doing fantastic work, but they’re very much out there. They’re a much bigger organization and they have bigger ambitions. Heffter’s model initially was to just find donors because the government would not support this work. So to find donors that wanted to fund research, and typically that research has to go through academic institutions with something like psychedelics, that’s the way you can advance it because you’re working with substances that are generally pretty highly controlled. But if you can wrap that around, if you can wrap the respectability of science and academic affiliations around this kind of work, then the regulatory authorities can come back and say, okay, you can do this work. You’re experienced researchers, you’re not crazy, you have an institutional framework, you got a clinic, et cetera, et cetera. That’s what has been the Heftfer Institute’s model all of this time.

McKenna:

And we have brought a considerable amount of legitimate funding, and funding through different institutions and different investors to this work. It was not our agenda necessarily to focus on psilocybin, but a lot of our work has been with psilocybin or supporting psilocybin research because psilocybin turns out to be almost the perfect psychedelic in a certain sense, perfect for clinical studies, and therapeutic use, and that sort of thing. Because it’s nontoxic for most people it’s not a problem from that perspective. It’s a kick-ass psychedelic. So you can go into deep places, but it’s not in any way challenging in terms of its impact on the body and that sort of thing. So it’s a very good psychedelic. It ticks all the boxes and only a few of the undesirable boxes.

Taraz:

Very few undesirable boxes, most of the desirable boxes. That’s what I’m understanding.

McKenna:

Right?

Taraz:

Okay. That’s Mr. Science. Dennis McKenna. Psychedelic Scene is an art and culture magazine. One of the things that seems to be an aspect of how to offer up to the collective mind access to the power of the plants, whether through ayahuasca, DMT, or psilocybin is proof to my mind in the form of artistic expression. Like Jimi Hendrix, was a blues guitarist, who took some acid, and played guitar. The next thing he comes back, he’s doing yada lada lada la. Alex Grey and his wife, are drawing biological things that have energy vectors. And so one I feel doesn’t need to take the psychedelic. Once the artist brings back a way to see things like, I think people get Alex Grey’s artwork, but, you know. Are you familiar with Alex Grey?

McKenna:

Yeah, of course I know Alex Grey. He’s a good friend. He’s a good friend and amazing work that he produces for sure. This is a good point that you make. The interface of psychedelics and creativity is one of the most important things about it. Yes, they are medicines, they can benefit lots of people from that perspective. But you don’t have to be diagnosed with any condition to benefit with psychedelics. From psychedelics, it appeals to creative people because inherently creative people are always pushing the envelope of experience and psychedelics facilitate that. The discoveries that you make or the experiences that you take from psychedelics you have to bring back in some way. Well, artists are well equipped to do that. They have the skills to depict those experiences, whether it’s through visual arts or music or poetry, or whatever. So psychedelics are a great companion for creative people and they should have access to this. They should not have to enroll in a clinical study in order to use.

Taraz:

Or get arrested.

McKenna:

But the situation is changing. I think they are going to be more available to people and I would like to see a situation emerge where you don’t have to be involved in a clinical study to benefit– or if you’re going to do a medical study. One of the concerns I have as psychedelics go mainstream is there’s a certain appeal to elitism. There’s a tendency if you have to go to a clinic and pay $30,000 to have a psychedelic session that’s approved, that door is closed to 90% of people who should be able to use it. Right? So we need to develop frameworks so that people can have access to these things in less formal situations. And that’s where the retreat model makes a lot of sense. The practitioners may not be MDs necessarily, but shamans have been using psychedelics for a lot longer than MDs have used them and they’ve learned a few things. So that’s one model that you can traditional ritualistic settings like what happens with ayahuasca and even mushrooms in the traditional context. What we need to do is develop means to create these environments where people can access psychedelics without paying an arm and a leg and without necessarily going to South America or other places.

McKenna:

Okay. Well, the issue is that, as psychedelics go mainstream, there are also people that can’t afford to go to a clinic or go to other countries like South America and do retreats. That becomes not accessible to them. And if anything should be accessible, psychedelics are it. Everyone should have access and the right to have these experiences. So what I’m hoping is that, in the next few years, the laws will change. They are already changing in different states and municipalities. So this process is going on that opens the door for people to effectively come out of the shadows and do their own retreat centers, establish their own retreat centers here in North America and Europe, and where they can offer psychedelics as just generally part of a menu of wellness or whatever alternative therapies that are accessible to people. And that these retreat centers can operate in the open because they don’t have to worry about it, they’re not breaking the law. And you see this happening in places like Colorado and Oregon. And a few other states are going to follow along where this is happening. So I think it’s a changing landscape here and, in a few years, psychedelics will be available to almost anyone who wants it at a fairly affordable price and in a way that doesn’t really impact the indigenous cultures that ayahuasca tourism does and that sort of thing.

McKenna:

I mean, ayahuasca tourism is a many-edged sword, it’s not entirely a bad thing. I organized ayahuasca retreats myself, that was what I did for ten years, among other things, before COVID hit. And I think it’s fine. But you have to think about the impact of ayahuasca retreats– the whole industry on the indigenous communities that they’re interfacing with and there’s a right way to do it and a wrong way to do it. And as we said before, always will be done. Any powerful spiritual technology will be used improperly and it will be used properly. And it all comes down to who’s doing it and for what motives, for what reasons.

Taraz:

Are you in your background of reading- because I’ve heard you talk a little bit about some of your influences. Like I know Jung was an influence of yours. Was Nietzsche ever part of your influence diet?

McKenna:

Yeah, no, I read Nietzsche. It doesn’t really resonate with me the way Jung did. But yes, I read Nietzsche back in the day, I mean way back in the day. Now when I was in high school I read that. It didn’t really resonate with me. Right. Unlike Jung, which I could appreciate, and also Mircea Eliade, who is an anthropologist, wrote a lot about shamanism. Those people were very influential for me.

Taraz:

Right, so part of the thing is in talking about the retreats and about legalities and science. One of the things with you, sir. Dr. Dennis McKenna, if I may, to me, art and artistic expression happen in a way that people can interface with a drawing, or hear a piece of music. The artist does something with frequencies, sounds, and expression. It’s deconstructed by the end listener. In your particular case, I’ve heard you make this statement about- I forgot who it was you were talking to, but- something to the DMT spirit molecule. That was a clip you did. And you’re at such a disadvantage because there are things you said ten years ago and then 50. But either case, please correct me if I’m wrong, but to the extent that you still relate to learning with the teacher and you had called out your brother at one point because he wasn’t doing psychedelics to your satisfaction at a certain point and you said, if you’re going to be a psychedelic dude, you better do psychedelics. And then later you’re like, maybe I was too pushy. Something like this, you self-corrected. But to me, part of the thing is the model that you guys brought forward, that you brought forward also, and your work with the Amazonians is the shaman model.

Taraz:

And to me, the shaman model is not about the shaman having medicine for himself, but on behalf of a society or a community of interest. You go, you subject yourself.

McKenna:

That is the whole point of shamanism. Like in the traditional context, the shaman, I mean, in the context of ayahuasca tourism, the shaman has been elevated to rock star status. All the focus on that, creates sometimes not always, but this creates resentment in the community. Like, people say, well, this guy, he’s just the guy that lives down the road and yeah, he practices this, how come he’s making ten times what I’ll ever make in a lifetime? It creates resentment. But properly, in the right cultural context or societal context, the shaman is just a practitioner, someone that serves their community. It’s very much as you said, they’re not doing it for profit, they’re doing it for personal satisfaction. And in those situations, I mean, shamans may charge a little bit of money or charge, or maybe you give them a chicken or something, but it’s a much less economically driven thing than it is in ayahuasca tourism because you’re talking about estrangeros, they’re coming from outside with fat wallets and many ideas of their own that may not be appropriate, but they bring.

Taraz:

And Go Pros and YouTube channels.

McKenna:

Yeah, the practitioners are going to respond to this because, like anybody else, any other entrepreneur, you want to give the customer what they want. Right? So what people get through the touristic approach to ayahuasca practice is not traditional. That doesn’t mean it’s bad. It has its value. It has its value for the people that go there and can afford it. I’ve seen incredible transformations and incredible healing on some of these retreats. That’s part of what has kept it going and kept me going with these because I can see the benefits. But I can also be aware that underneath the surface, it’s not perfect. It’s not perfect.

Taraz:

Now it seems to me that you have done an amazing process of subjecting yourself firsthand to psilocybin, DMT in the form of ayahuasca, had the conversations in the actual Amazon, come back here through San Francisco and corporate venture capitalist America, and help startups like I forgot what the genesis? Or one of these companies you sort of helped found, bring together people from different areas. It seems to me- you may not be comfortable with the concept, Dennis, but I do believe that you are a shaman of some kind. Maybe you’re a reluctant shaman, a hesitant shaman, but you speak the language of corporate America, of science, also art, and internationalism, and you can try and find another framework, but there isn’t really anyone that could bring these things together like the accident of your life has done. Does that make sense, or am I just reaching? Have you ever thought of it that way? It seems to me you’re like a vessel for something.

McKenna:

Yes and no. I’m not a Shaman in the sense that I’m not a practitioner. I don’t pour the medicine. I don’t give the medicine to people. What I have done in the past is organize these retreats. So I create environments where people can come and where real shamans can run the ceremonies. I have never felt a calling to do that, nor have I felt qualified. I feel like I’ve only been involved in this for 50 years, and I’m not qualified. I don’t mind a lot of people. I do think one example of that is people, they’ll go to a retreat or they’ll go to South America, they’ll do a few ceremonies, you know, and the next thing you know, they’re hanging out their shingle. They’re not really prepared to do it. It’s not an easy path. Becoming an Ayahuascaro. You have to do the whole dieta thing, and it’s discipline. It’s like any spiritual discipline. This is sort of what I mean when I say there will be abuses. But people, not necessarily intentionally, but people that want to practice this really need to make a commitment to study and explore all these plants.

McKenna:

The dietas that are traditionally done in the Ayahuasca tradition, the plant teachers, if you will, the plant teachers that they have to learn how to use, you can think of them, as it’s analogous to an academic study. In academics, if you want to study physics or astronomy or something, well, you have to read all these books, right? And you have to go to classes, and you have to do these things. Becoming a shaman is similar, except you’re not reading books. You’re getting acquainted with plants. The plants are the teachers. Think of the plants used in the dieta as the library that the shaman must digest literally ingest, in order to understand the properties of these plants. This idea of the plant teachers, the Ayahuasca is a plant teacher for the shaman, as much as anyone else. Ayahuasca is like the master teacher that introduces through which the shaman can learn how to use all these other medicinal plants. I mean, Ayahuasca is made primarily from two plants: those go into the DMT plant and the vine. But it’s at the center of a whole pharmacopeia of plants that are used occasionally with Ayahuasca, more often by themselves.

McKenna:

But it’s in the altered state provided by Ayahuasca where the shaman can learn how to use these plants, and how to apply them in their practice. So it’s very much like a person who wants to become a doctor, literally. That’s what it is. You’ve got to practice certain skills, and you have to acquire knowledge. And the way you acquire knowledge in that tradition is through doing the dietas.

Taraz:

Right. But I must say, if I’m going to go study at a university, it’s nice to have a consensus behind the validity and stature of a university. And in your case, you’re a person who for 50 years has been you’ve been around Ayahuasceros that know their stuff. You’ve been around the weasels, you’ve seen it come, you’ve seen it go. Very hard for anyone in this society to then enter Ayahuasca, because, to me, the difference is mushroom grows. It’s a single shot, boom, you got a mushroom. As long as it’s not poison, you’re okay. But it talks to you about hyperspace and outer space and blah, blah, blah. Ayahuasca is the earth spirit molecule or something like this, requires a chemist, a brewer, and an Ayahuascaro to bring together. And if you don’t know if the guy is good or not good, it’d be great if there was a Dennis McKenna-credentialed checklist, like, what are the ones that you vetted? Because people would trust you. But when I’ve seen on YouTube different people that go to do Ayahuasca, and then they’ve given sugar cane, and you’re like, oh, sorry, that’s $6,000 later, right?

McKenna:

No, it’s uneven. I mean, there is no underwriters laboratory or Good Housekeeping seal of approval for these. There’s no official organization that rates ayahuasceros, although there are a few professional organizations of ayahuascero but there’s no…Probably the best source of information about practitioners, ironically, is check out TripAdvisor. I know they didn’t mean it that way, but if you go to TripAdvisor and you put in ayahuasca retreats, a whole bunch of them will come up, and they have reviews, which is nice.

Taraz:

Of Ayahuasceros and Ayahuasca trips? oh, wow, that’s cool.

McKenna:

Of their Ayahuasca retreat experience, because that’s how TripAdvisor works. People go to a hotel or go to a place, and they post these reviews. So that’s a good way. Not necessarily. You want to check your sources. It helps if you know the ropes and know some people. But as a first pass, if you’re looking for an Ayahuasca retreat, you could do worse than go to TripAdvisor.

Taraz:

It’s funny how things, how this medium, has democratized things like being able to speak with you in person. You’re in British Columbia, I’m in Arizona. We haven’t met, but you’ve touched my life in so many ways, and it’s really an honor to get to meet you. But because of the technology, it’s like, hey, how are you doing, Dennis? Hey, buddy, you know what? I met Dennis McKenna:. How cool is that? Blah, blah, blah.

McKenna:

Yeah, that’s one thing that the internet has done is democratized this knowledge of this access. So that is good. What’s our time frame?

Taraz:

Our time frame? I was going to wrap it up here with you because you’ve been so kind. One, you’re going to Denver, I believe, for the MAPS thing? So I believe you may meet the publisher of our magazine, Psychedelic Scene. His name is Jason LeValley, and if I haven’t done badly by him, I’ll tell him to say hi to you.

McKenna:

You won’t be there, I take it?

Taraz:

Oh, no, my means are limited. I’m one of those guys. I’ve got a couple of grams of shrooms in the kitchen. I’m about to do some in the near future. And that’s about $80 is what I can do. Denver is a little more expensive. It must be very strange…

McKenna:

Denver is ridiculously high-priced.

Taraz:

I can’t believe that you and your bro were born in Colorado in a little pea dunk town, whatever the story was. And here Colorado becomes like an epicenter of the legitimizing of all this. Is that an accident? Is it fate? How do you relate to that?

McKenna:

I don’t know. I’m as surprised as anybody.

Taraz:

Okay.

McKenna:

I guess it’s destiny. Maybe we planted the seed of the vine in Colorado and then it spread throughout. But most of that took place before Terry, after Terry left Paonia and I was still stuck back there being the younger brother. But, yeah, Colorado, it’s a remarkable transformation. It’s a lovely state, and I still have many friends there, and I’m happy to see that it’s become one of the epicenters for this revolution.

Taraz:

Right.

McKenna:

And that’s a cool thing, and I’m proud to be part of it and happy that I could say I grew up in Colorado. Well, some people would say I’ve never grown up, but you know what I mean.

Taraz:

I must say that that’s one of the wonderful things about your energy. That’s why I was trying to reach out to you because somehow I think you’re stuck at… What was it? Were you 19 or 20 in La Chorerra?

McKenna:

I was 19.

Taraz:

That’s my son’s age. He’s driving to Toronto

McKenna:

I was 20. Sorry, I just turned 20

Taraz:

20-year-old kid all of a sudden in the middle of the Amazon, interpolating mystical processes in their thing. I think you’re still that 20-year-old right now, no matter what it looks like on the outside, the sweetness, the vision, et cetera, and that’s me imposing and projecting on you, even though we just met the first day. So, anyway, I want to say thank you on behalf of Psychedelic Scene and myself. People, you should visit Dennis McKenna. You know him, McKenna Academy, espd.com.

McKenna:

McKenna.academy is the website. McKenna Academy and ESPD55.com. There’s an ESPD50.com, but go to ESPD 55, and it’s all there. Those are the two key URLs. If they want to get in touch and see what materials are on there and so on. So that’s the place to go.

Taraz:

Okay, well, I would ask you a million other questions and try and put you on the spot, but I think you’ve been very gracious, and I want to thank you. Any thoughts, last feelings, or statements you’d like to share with our Psychedelic Scene people?

McKenna:

Well, I guess a couple of things: Keep your powder dry, keep your skeptical antennas well-tuned, and don’t let people hand you any wooden nickels. Rely on your own intuition and your own perspective on these things. There are many rabbit holes to go down. Just maintain your perspective and keep an open mind and explore. I mean, it’s there to be explored at the end. What psychedelics come down to are an intense relationship between a molecule, a plant, a teacher, if you will, and you. You’re the other part. You’re the other party participating in this, and you can put it into any framework or retreat framework, or therapeutic clinical framework. At the end of the day, it’s you in the relationship with the medicine, however that plays out, that’s where the rubber meets the road. So you want to take care to keep that an optimum situation. You do everything you can to be prepared for it. We could go on and on about set and setting and all that, and you should do all that, and you should be informed about it. At the end of the day, though, you have to be ready to say, okay, I’m ready to let go.

McKenna:

You have to let go and surrender to it and see what happens. You have to step away from the controls and put it on autopilot and see where you’re going to cruise to. Something like that.

Taraz:

I like it. You got to cruise. That’s the thing. Thank you so much, Dennis.

Dennis McKenna has conducted research in ethnopharmacology for over 40 years. He is a founding board member of the Heffter Research Institute and was a key investigator on the Hoasca Project, the first biomedical investigation of ayahuasca. He is the younger brother of Terence McKenna. From 2000 to 2017, he taught courses on Ethnopharmacology and Plants in Human Affairs as an adjunct Assistant Professor in the Center for Spirituality and Healing at the University of Minnesota.

Gallery

Recent Articles

All in a Name by Daisychain–Album Review

•

June 26, 2025

Richard E’s “To the Moon” Reimagined on New Remix EP

•

June 23, 2025

Loading...

Movie Club Release New EP Black Mamba with a Short Film

- Jeff Broitman