Pepperland: the Untold Story of the Infamous Psychedelic Rock Venue, pt. 2

Pepperland: the Untold Story of the Infamous Psychedelic Rock Venue, pt. 2

Sigh of Relief

Despite the lukewarm review of Pepperland’s official launch in The Berkeley Tribe, the show was a success, and the club was drawing people and big-name acts. The following weekend (Sept. 25 & 26, 1970) Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention performed as part of their ‘reunion’ tour. The set was recorded and later released in 2020 as a part of the Mothers 1970 CD box set commemorating the 50th anniversary of the 1970 Mothers (Zappa Records / Universal Music). Two weeks later, on October 16 & 17, 1970, Pink Floyd performed two somewhat sparsely attended but highly memorable shows. Certainly well-regarded by those lucky enough to see it. “Pink Floyd. Wow! Man, I was there!” Pepperland stage manager Mapes Root recalled proudly, “Incredible show!” And Root’s sentiment is shared by many.

“I went to both Pink Floyd’s Pepperland shows on Oct.16 & 17, 1970, and I still remember to this day how awesome the whole experience was!”, attendee Ezra B. Eddy IV wrote in 2022. “It’s hard to believe that it didn’t last longer than it did!!

Pink Floyd performed two somewhat sparsely attended but highly memorable shows.

The whole submarine effect was really well done!!! And those speakers were fantastic; it was like an “Alice in Wonderland “experience come to life!!!!”

The Pink Floyd performance is among the most celebrated in Pepperland’s history. The venue’s low stage was too small to accommodate the groups’ massive gear, which was largely set up on the dance floor. Pullum and The Brotherhood of Light projected fish-eye photos of farm animals at the painted portholes on the walls in reference to the Atom Heart Mother album, (Pink Floyds’ first #1(U.K.) released a few days before. An estimated 500 people, primarily teenagers, attended the first of the two-night performances.

“My girlfriend and I drove up from Palo Alto to see Pink Floyd,” shared an anonymous attendee. “Pink Floyd was set up against the back wall, opposite the entrance, on a very low riser. The floors and exposed metal rafters reminded me of a roller rink I used to go to as a kid. There were slide projectors up in the metal rafters projecting fish-eye photos of farm animals. Keyboardist (Richard Wright) had a joystick that he used to swirl his synth and other sounds around the room or have them rip through the room, front to back, to great effect. The big Glyph horns were set up in the corners, and there were Shure vocal columns set up every 20 feet or so along the walls in between. There were no more than 500 people sitting on the floor in the center, with some folks sitting up inside the big Glyph bottom horns!”

The first night of Floyd’s two-night engagement became well-known for the group’s brilliant performance and also for its technical difficulties. In the weeks leading up to the Floyd shows, the venue had been having some issues “blowing fuses.” The weekend before the show, Pepperland was shut down to “get everything together” and give electricians time to “rewire

Pink Floyd’s massive set-up taxed the venue’s power supply to four power failures during the group’s opening song, “Astronomy Domine”

the stage.” But to no avail. Pink Floyd’s massive set-up taxed the venue’s power supply to four power failures during the group’s opening song, “Astronomy Domine”, ultimately taking the group nearly twenty minutes to complete. Another failure on the finale of the two-hour show forced the band to re-play the ending of the song for the recording. The entire performance, including the power failures, was recorded using a single-point stereo microphone about ten rows from the stage. All of this can be heard on a two-hour bootleg of the show officially released as a 2-CD set in 1998 called Pepperland in the West (Highland Records). Listen HERE.

Concert-goer Richard Gillen recalled the two nights, writing, “Just as the Floyd were finishing the last song, the P.A. power failed! The band was as shocked as we were in the audience. After anger and groping around, they finished with what you hear at the end of the recording. I brought friends to the next night, and you could see Roger Waters just cringing as they hit the last notes. Thankfully, the power held up, and we all breathed a sigh of relief.”

Pot Problem? What, pot problem?

Happenings during the last four months of 1970 earned Pepperland the moniker Woodstock West in more ways than one. Accusations of open and frequent drug use at the venue caught the attention of city leaders, and promoters Ben Blatt and Nat Shind were under constant pressure to toe the line from local officials. On one occasion, San Rafael City Councilman Harry Barbier falsely claimed he was a fire marshall upon barging into the Pepperland and threatening to put the rock hall and the Bermuda Palms “out of business,” later stating, “it ought to be closed. They’re all smoking pot down there!” The quarrel played out publicly in the local Independent Journal with San Rafael Mayor Paul Bettini stating that the “purple-painted building had drawn more complaints than any other item” in his time as mayor. City council meetings turned contentious with continued accusations towards the promoters of catering to large crowds of underage dope smokers getting high. The San Rafael city building inspector declared the venue’s legal capacity to be “only 1,850,” although shows often drew more than 2,000. Pepperland’s attorney Daniel Weinstein fired back, accusing city leaders of not doing enough to give young people a place to go and keep them “off the streets.” Meanwhile, memorable performances by Joan Baez, Hot Tuna, The Incredible String Band, Leon Russell, and The Grateful Dead with David Crosby filled Pepperland with high-schoolers “jammed together, sitting on the floor smoking marijuana and hashish openly,” giving all the rumors and accusations credibly.

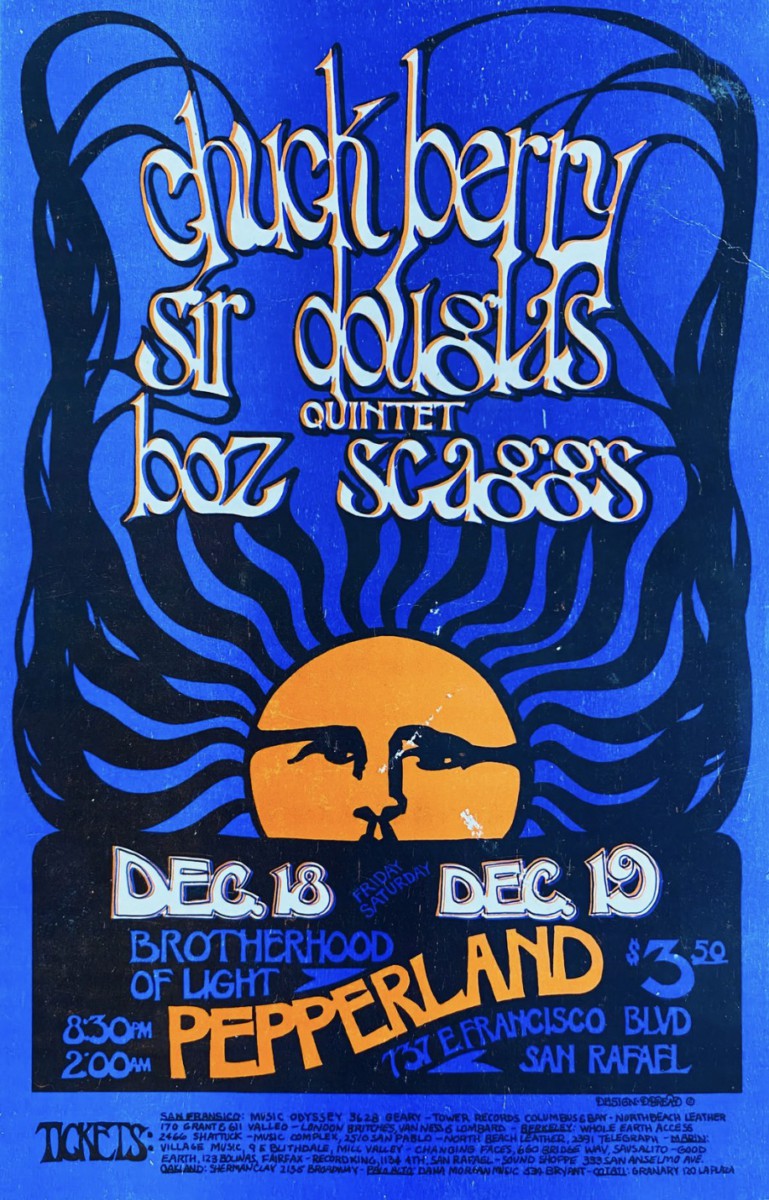

The Joan Baez shows on Sunday, December 20, 1970, were some of Pepperland’s most successful events. Baez performed two one-hour shows at 7 p.m. and 9 p.m., billed as “An Hour with Joan Baez.” Founder and director of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, Barry Olivier (est. in 1958), served as the show’s producer. Olivier also promoted a pair of Muddy Waters

The next night was advertised on the Pepperland marque as “Acoustic Dead Jam,” but it turned out to be an electrified Jerry Garcia, Phil Lesh, and Bill Kreutzmann backing up David Crosby.

and Big Momma Thornton shows at Pepperland and Berkeley Theater in April 1972. Records show “Folklore Productions” produced the Baez shows in an agreement documented between Olivier and Shind, with Olivier having rented Pepperland for $500 plus $250 to cover staff and crew, including coat check, security, and program salespeople who earned 20% on every program they sold.

Neither the cold December rain nor a bomb threat could keep people away from the heavily advertised Baez performances; the line for each show reportedly went around the block, and parking was “as bad as Kezar” (Stadium, San Francisco). The shows opened with a popular Sonoma County country-rock group called Frontier. The combined performances drew nearly 7,000 concert-goers, well above the city-stated capacity of 1,850 per show, and markedly better than the Chuck Berry show two nights earlier, which saw less than 1,000 attendees. Police later reported that, around 9:25 p.m., a male caller had phoned Pepperland and stated, “There’s a bomb set to go off in Pepperland at 10 o’clock; we don’t dig Joan Baez around here.” Pepperland security, led by Nathaniel Weathers, had quietly but intensively searched the building, the crowd, and the grounds for over an hour and found nothing. No one at the show even knew. The next night, December 21, was advertised on the Pepperland marque as “Acoustic Dead Jam,” but it turned out to be an electrified Jerry Garcia, Phil Lesh, and Bill Kreutzmann backing up David Crosby. Numerous other Bay Area artists, including New Riders of the Purple Sage, joined the mostly electric jam. While the Grateful Dead (whose rehearsal space on Front Street was directly behind the Bermuda Palms) played at 721 E. Francisco Blvd. when it was known as Euphoria, this is the only known time the Dead performed at “Pepperland”.

Pepperland finished 1970 (having been repainted from “passionate purple” to “subdued gold”) by hosting a New Year’s Eve show with Sly and the Family Stone, one of the hottest acts in music at that moment,. The Bay Area funk group was just a year out from their triumphant performance at Woodstock. The show drew a great crowd, but they waited and waited–and then waited some more. “Sly didn’t even go onstage until at least 2:30 a.m.,” Mapes Root recalled. “But people stayed around.” It was the beginning of an infamous pattern of behavior for the funk legend. “He was so coked up, high out of his mind.” When the 1970 New Year’s Eve show finally began, 1971 was already two-and-a-half hours old. It was a fitting end to a year that saw many highs for Pepperland.

Good Music, Bad Business

1971 would see a slew of great artists perform at Pepperland, coupled with a slew of problems leading to the club’s demise. KSAN-FM in San Francisco recorded The Youngbloods’ live set on January 22, which was remastered and later released on a double CD in 2016 as Live at Pepperland, California ’71(Keyhole Label). Taj Mahal, Tower of Power, John Lee Hooker, Sons of Champlin, Spencer Davis, and Steve Miller were just a few of the fifty different acts that performed at Pepperland in 1971. The creative side certainly attracted the best. However, the business end suffered from inconsistent scheduling and shows often losing money.

According to Charlie Kelly, (a 42-year roadie for the San Francisco psychedelic group Sons of Champlin), “When I collected the money for a Sons show there, the two (promoters Blatt & Shind) who were losing tons of money, got into the kind of drug-fueled argument that made you want to get out of the building before one of them found a gun.” In April 1971, after continued financial, legal, and political pressures became too much, Sameuls, Blatt, and Shind skipped town. According to stage manager Mapes Root, “they were always just skating by and finally running off with the money after a

Sly didn’t even go onstage until at least 2:30 a.m.

show.” On April 13, 1971, local papers reported, “Shind and Blatt had disappeared following their last show two weeks ago.” Whitey Litchfield admitted, “The handwriting was on the wall. Bills have been mounting for months and they never paid on the lease. They were harassed with stringent regulations by the city council, and the police chased them out of town. They had no money to live up to their promises.” Blatt and Shind (who had been living in Sebastopol after moving from Novato), had already dropped out by the time word hit the press, leaving behind a reported $50,000 in unpaid expenses. The club, considered “out of sight” by local youth, was now out of money. Following a benefit show for Native Americans on April 11, 1971, featuring Hot Tuna, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and Lizard, Pepperland would lie dormant for nearly five months.

Meyer Sound

Pepperland 2.0

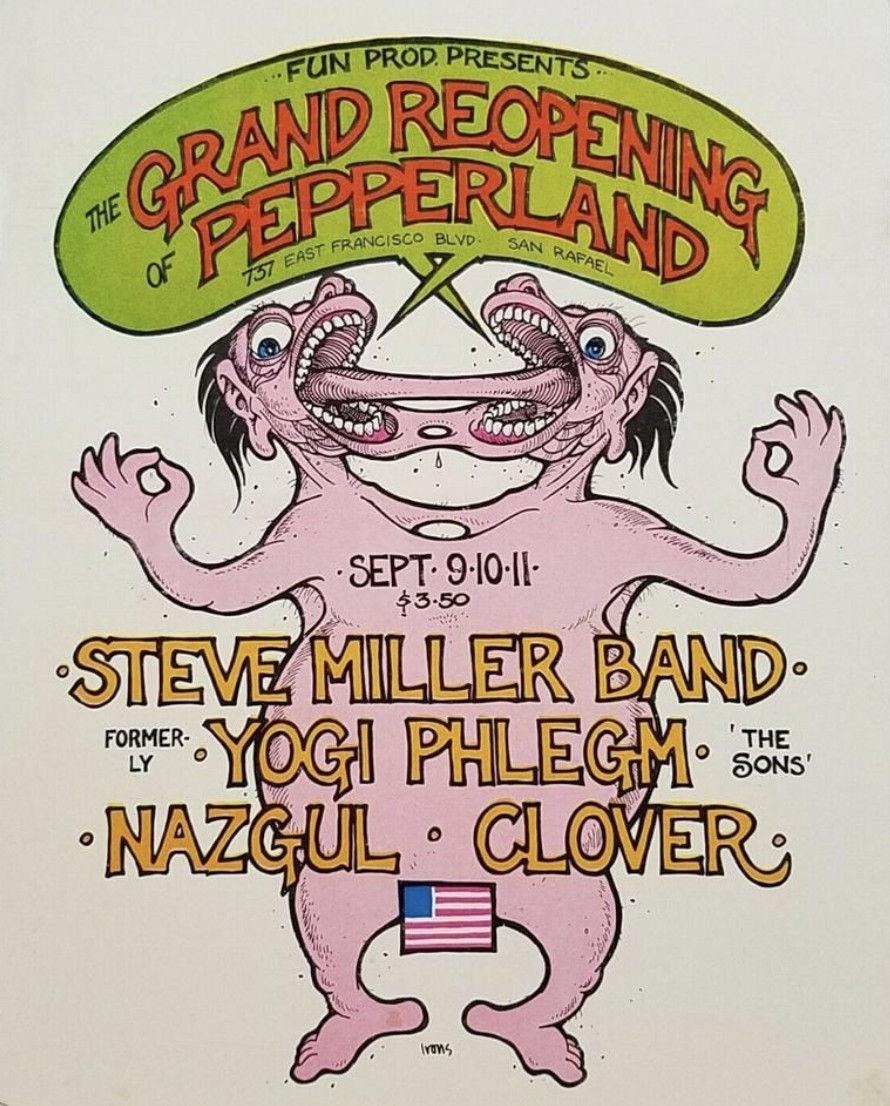

Pepperland held a “Grand Re-Opening” on the weekend of September 9th, 10th, and 11th, 1971. Opening night was headlined by The Steve Miller Band and the former Sons of Champlin (billed as ‘Yogi Phlegm’), alongside local groups Nazgul and Clover, the latter led by vocalist/guitarist Alex Call. Clover first played at 721 E. Francisco when the venue was still known as Euphoria, and ultimately performed there more than any other artist, sharing bills with Linda Ronstadt, Big Brother and The Holding Company, Elvin Bishop, Cold Blood, and Leon Russell, among others. “Some things I see clearly and other things are like the Viking sagas, which weren’t written down,” described Call. Alex would later help write songs for Huey Lewis and the News, Pat Benatar, and Tommy Tutone, including the latter’s 1981 hit “867-5309/Jenny.”

“Clover was hot right then, I think we were still pre-Huey (Lewis). We had legions of Marin High School fans, who showed up in droves that night. We blew Steve Miller off the stage, but he put us in our place a couple days later by bringing us to his office in San Francisco and showing us his national tour map and room full of guitars. We had neither.”

Clover performed again two weeks later with Mike Bloomfield, Stoneground, and Mike Finnegan; a well-regarded two-night engagement. Fun Productions presented both events under promoter Skip Whitney. Whitney had managed to retain some of the original employees, and the Brotherhood of Light show. “We took over after them (Blatt & Shind). Pepperland

Even booking renowned artists Linda Ronstadt, Muddy Waters, Big Momma Thorton, and Van Morrison wasn’t enough to save the club.

2.0. It was such a cool time in Marin. We were booking great shows, but my business partner ran out of money,” and later promoters were unable to maintain what Whitney had continued. Even booking renowned artists Linda Ronstadt, Muddy Waters, Big Momma Thorton, and Van Morrison wasn’t enough to save the club, as the venue presented just over a dozen shows in 1972 under various promoters. The questionable activity of former promoters Blatt and Shind had soiled the reputation of Pepperland in the eyes of city officials. The Marin Performing Arts Guild suggested a partnership with the Marin County Supervisors to revive the concert hall in late 1972, but the county was tired of the “nuisance” and ultimately declined. Heavy flooding in Marin County during January of 1973 caused damage to Pepperland, ruining flooring and rugs. The club limped along before unceremoniously closing for good in early 1973, becoming a Carpet King Remnants store later that year. The original building, with its incredible music history, still stands today at 721 E. Francisco Boulevard in San Rafael, California.

Related: The Music Never Stopped: The Grateful Dead’s Enduring Legacy

Courtesy of Thelen Creative

Gallery

Recent Articles

Loading...