Interview: Malcolm Bruce of “Heavenly Cream”

Interview: Malcolm Bruce of “Heavenly Cream”

Malcolm Bruce: Hello sir! Can you hear me?

Bill Kurzenberger of Psychedelic Scene: Hello Malcolm! Yes, I can hear you. How are you doing today?

I’m great. I’ve got my protective eyewear on, even though it’s 7 PM in London. I… I’m pretending to be cool. So there you go. How’s it going with you? How’s Arizona? I miss it. It’s hot there, it’s cold here.

Well, actually, I miss Arizona a little bit too. I’m in Columbus Ohio, and we’re starting to get into wintertime – almost getting into wintertime in the next month, so we’re creeping down with our temperatures here.

I played in Columbus, it’s gorgeous there actually. Yeah, it’s a whole different thing from Arizona, that’s for sure. Beautiful part of the country though, right?

Yes, it is! I do like central Ohio quite a bit, yes.

Fantastic. Yeah.

Well, thank you for taking the time for this interview with Psychedelic Scene. We definitely appreciate it.

My pleasure man, absolutely – no, we appreciate the support for the record, and yeah, absolutely.

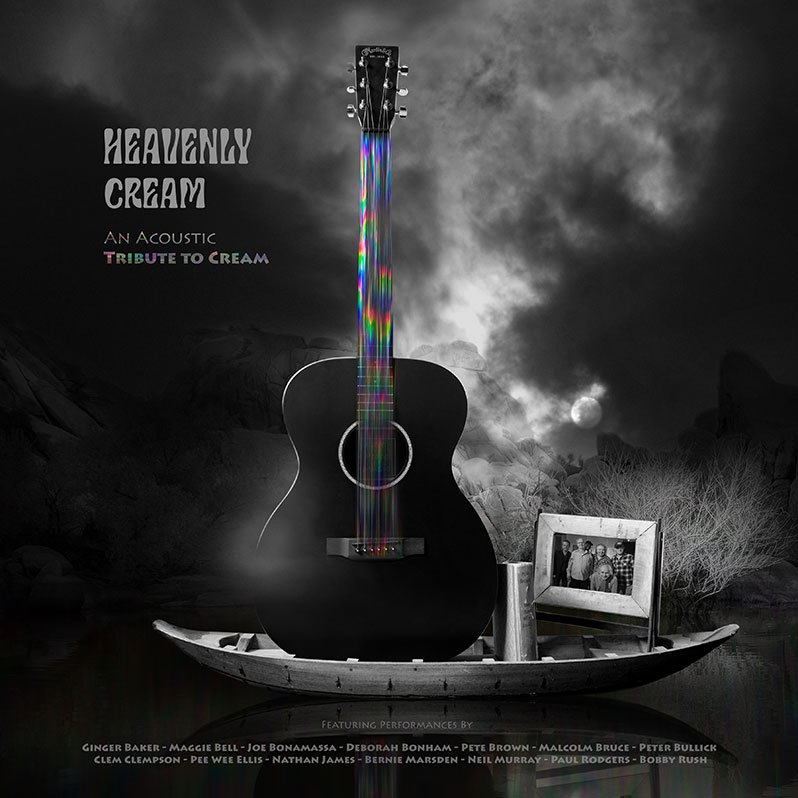

So yeah, let’s dive in and talk about Heavenly Cream. You know, what a fine tribute! It’s hard to imagine a finer tribute to your father and to Cream’s legacy. How did it all come about?

Well really, we have Pete Brown to thank for it. And in case anyone doesn’t know, Pete was my dad’s chief songwriting collaborator, as a lyricist wrote many of the lyrics for Cream’s songs like “I Feel Free”, “Sunshine of Your Love”, and “White Room”, etc. So Pete really instigated the whole project, he was talking to of course Valley Records, and they sort of cut a deal along the lines of “Hey, let’s make a record, let’s make an acoustic tribute to Cream, and shoot a documentary. So it’s something a little different in that sense, it’s not just a straight-ahead, ahem, you know, covering the songs as the original band did. It’s a different sort of shining a light on it from a different perspective, and I think it’s kind of interesting to do that. And I think it sort of… a song is a song, right? And you can perform it in many different ways, and I think if it’s a good song, it kind of will hold itself… holds its own, I guess. You know?

Sure, sure.

Because you know, the blues rock idiom, so much of that is about playing, you know, like feedback and guitars and the vibe and the sound, and that’s sort of beautiful and gorgeous and infinite within itself, and the jam – jamming improvisational aspect of all that, but actually when it comes down to it, these songs, it was nice to kind of say let’s just strip it down and have the songs, and in that kind of simplest form in a sense, without all the bells and whistles… too much of the bells… well, different kind of bells and whistles.

Different bells and whistles, right? A violin instead of electric guitar, or saxophone on “Tales of Brave Ulysses.”

Yeah. I mean, I don’t want to simplif… I don’t want to kind of undermine what we tried to do. But I think you probably know what I mean. It’s like, instead of the wailing guitar with the wah-wah, it’s a trumpet.

Right. Yeah, I found that to be an interesting… interesting choice. You know, you have several talented guitarists on the sessions, and you know, several of which would have been able to wail if that was the choice. But I found that to be an interesting decision for it to be an acoustic tribute instead.

Yeah, absolutely. It’s like, I guess the metaphor is like OK – tie one hand behind Joe Bonamassa’s back and see what he can do, right?

Right.

But I mean, you know, that again, Joe is so amazing. It was great to have him on the session, and obviously, you know, he can play an acoustic guitar as well as anyone. So yeah, it was really interesting to have those kinds of guys come in with a limit… you know, define a limitation, and then see how they would react to that. You know, how would their creativity be brought to bear on a situation? It wasn’t “you can do whatever you want” you know, it’s like – “no, you can do whatever you want as long as it’s on an acoustic guitar.”

Within this framework.

Yeah, and you know, Joe’s amazing, and Bernie Marsden, and you know, I think we were really lucky that the group of people we got together for this record, everybody was there for the right reasons, whether it was a direct connection to the tradition, or just their love of the music or you know, in Ginger Baker’s case, he made the music in the first place. And Bobby Rush, you know, I mean having somebody like Bobby, you know, it brings a certain weight to the proceedings as well. Because he’s like, again, one of the guys from that – you know, that created that whole thing. So yeah, I think from all perspectives it was really nice. I kind of wanted to take much more of a sort of supported role in the thing, and you know, I think I did. I played a bit of bass, played a bit of guitar, played a bit of piano, that sort of thing.

Wave them away! Keep them out of shot! (Laughs) Is that family, or…

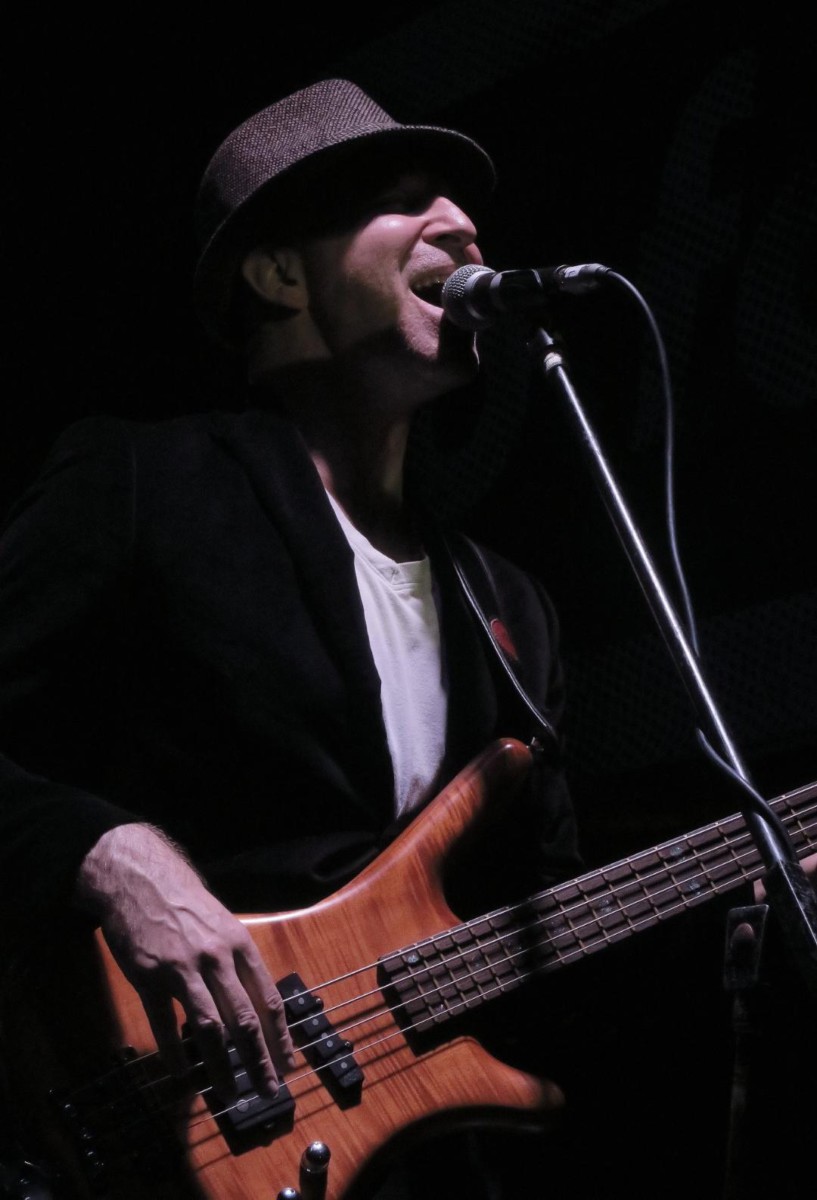

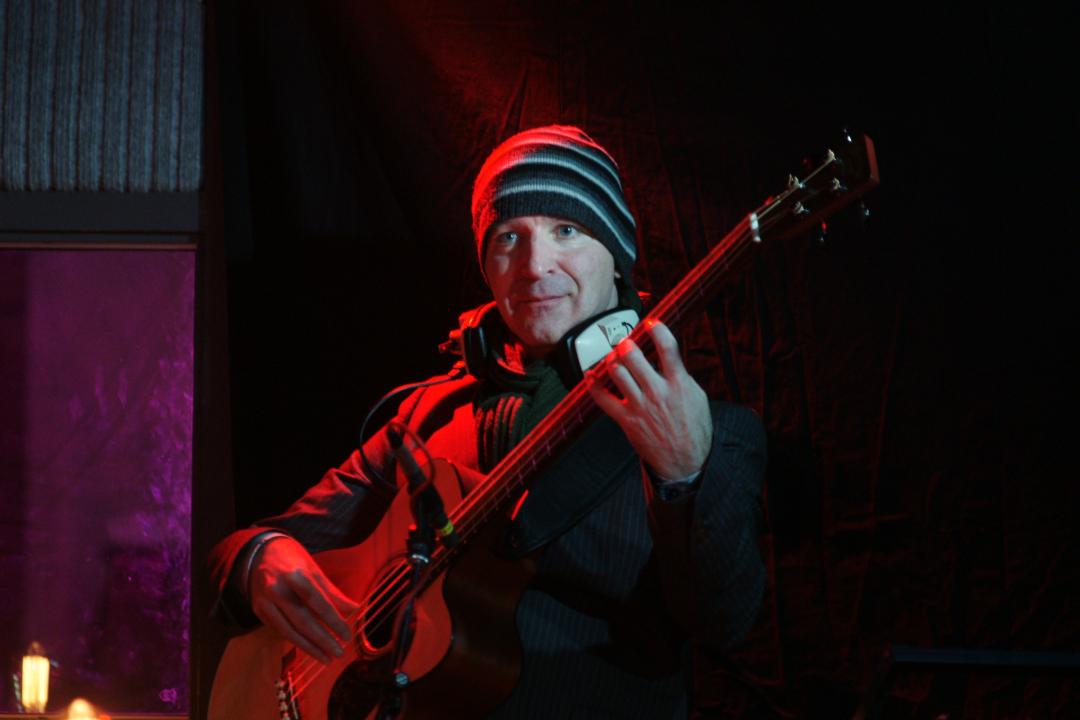

Courtesy of Malcolm Bruce

Yes – yeah, my wife didn’t realize the interview had already started. (Laughs)

That’s OK, bring the wife in, bring the wife in, it’s fine. (Laughs)

She’s in the other room there…

Yes, and from your perspective, yes, you were able to contribute piano, ah, and bass, so you’re a multi-instrumentalist…

Yes, I’m…

How many different instruments do you play in total?

Well, I would say that I play the guitar, the bass guitar, and the piano to a very good standard, but I can play a lot of other instruments badly if you need it. (Laughs) If you need like a slightly dodgy recorder player, or I can play a bit of alto sax. I played the sax for a couple of years and I loved it. I played the violin for about seven years, I can play some… I can play a beat on the drums, but I wouldn’t say I’m, you know, a proper drummer. (Laughs) But yes, as a guitarist, a bass player, and a piano player, I really – and continue on a daily basis – to practice and woodshed and all of that stuff. So you know, as I progress, I’ve got a record coming out next year and you know, I hope that I will get a bit more recognition for my thing.

But it’s so different from… it’s a weird thing to be the son of somebody like my dad who’s had that kind of career and fame, and all that kind of stuff. Because you tend to be candy? in the shadow a little bit, and then the expectation is that you’re gonna be a blues rock artist yourself, so I found a lot of that stuff.

As a writer, I’m doing and continue to develop my own voice which is sort of outside of that, it’s something a little bit different. So hopefully, somebody will listen to that next year when it comes out. You know, so yeah, I mean I just love being involved with this record. In a way, it’s a transitional thing for me, to pay tribute to my dad. I’ve done it quite a lot over the last ten or fifteen years in different bands and in different ways. And you know, I love my dad, I’m so proud of him, and respect and admire his achievements. So it’s just a lovely thing to do with this, and with all those guys, you know. And Pete Brown was my good friend, he passed away earlier this year, but you know, he was my dear friend. I wrote songs with him, I knew him before I was born, you know, so there you go. (Laughs)

Well yes, and really, like you were saying, really an impressive ensemble, but especially with Pete, with his involvement, um, and with Ginger’s involvement. One of our writers had the opportunity to interview Pete shortly before he passed earlier this year, and I was very sorry to hear of his passing. And he indicated that I think in the case with Ginger, that it was – were those the last tracks that Ginger recorded, as well as Pete, possibly?

Yes. Definitely. Ginger, those were the last recordings as far as I know, those were the last recording sessions that he did. His health was failing by that point, but I don’t think it impacted his performance. You know, you could tell he wasn’t like, he wasn’t this aggressive, as physical as he perhaps used to be, you know he’s famed for that kind of – I don’t know whether the guy from… what’s your… Animal from the uh… what’s that famous…

Oh, from the Muppets, sure.

The Muppets, yeah. I don’t know whether that – ‘cause I always thought that looked like Ginger, but I’ve heard different drummers claim it for themselves. But I mean, that kind of crazed, incredible, animal sort of physicality that Ginger was well-known for. And you know on these sessions, it was much more refined, elegant?, dynamic, and orchestrated. It’s really, really gorgeous what he did, I love it. But yes, I think those were the final sessions.

Now with Pete, we actually made – earlier this year we made Pete’s solo record called The Shadow Club. So we actually recorded a whole record of Pete’s original songs. That’s coming out next year, and that’s me on bass, a drummer called Richard Bailey, who is incredible. He played with Bob Marley, but he also played on Jeff Beck’s Blow by Blow, and was Steve Winwood’s drummer for over a decade, I believe. He played with a British kind of neo-soul funk band called Incognito. So, Richard’s one of the most respected drummers on the U.K. scene. So he was on it, and I think Joe Bonamassa is also on Pete’s solo record. And Eric Clapton plays on the title track “The Shadow Club” as well. So that’s coming out next year. We managed to finish it before Pete passed away, but it was being mixed while he passed away.

But I think he was really proud of it, and he realized, you know, he realized it was his final achievement. I think it’s probably the best record he himself made, and I know that he was proud of it. So hopefully, we’ll talk about that next year when that comes out.

Well, we’re certainly looking forward to hearing that too, and it seems like a fitting… it’s unfortunate that Pete didn’t survive to see its release, but it seems like a very appropriate swan song for him.

Yes. Well, if we’re going to be psychedelic about it, you know, nothing really is born or dies, we’re all just kind of living in a hologram. So you know, he’s somewhere in that Akashic record, Pete will be hovering vibrationally and will be digging it, you know, on whatever level, so there you go.

Did you find it harder for this – for Heavenly Cream being acoustic, did you find it – did having it be an acoustic album make it more challenging to get to those kind of psychedelic places, did you find? Were you able to explore those in some of your other recent sessions?

Yeah. I mean, I think this record is a, it’s a simple heartfelt tribute. It’s not necessarily – I don’t think the aim was to get into those deeper meanings and deeper levels of things. It’s – you know, it’s a studio record done in a particular way with a particular group of people, and it’s beautiful. You know, there’s a lovely sensitivity in the record, and you know, lovely vocal performances from Paul Rodgers and Deborah Bonham? And all kinds of people and I think it’s a very loving record, you know it’s all done for the right reasons. But you know, is it kind of – you know, I think for anyone who understands Cream in a deep way will understand what it stands for in terms of where it can reach potentially in that spiritual sense, the exploration, the improvisational element, and where that can go. And this isn’t that kind of record you know, otherwise it would be a sort of ten-disc set with like hour-long… you know it’s not like a Grateful Dead record, not a Grateful Dead sort of you know, opus, twelve hours worth, I mean you know? (Laughs) I mean those things are incredible obviously, but it’s just sort of a different thing.

More concise.

Yeah, more concise. And I mean, I’ve toured with Kofi Baker, Ginger’s son. We did quite a lot of playing Cream’s music over the last few years, and we did touch on those things. You know, I think you can – in a live setting, it’s much easier to open out and to kind of get that synergy with an audience, the kind of energy that goes between the performance and a room inside an actual physical space. And you know, so I know that Cream has that – Cream’s music has that ability to really get unto those levels. But I think this record is just a lovely tribute to the songs and with some – you know, it doesn’t get much better than Paul Rodgers, let’s put it like that.

True. Very true. What was your favorite track on this release to record?

Well, I love “Sweet Wine,” because my mum co-wrote it with – my mum co-wrote the lyrics with Ginger back in the day. And my mum still lives down the road from me here, we meet up all the time… so it’s just kind of nice for her. I think it’s really nice for her, ’cause she’s very humble, she doesn’t make a big deal about those things. But she was around – you know, she met my dad when she was a teen – when they were both teenagers, and my mum used to love the early British music scene, you know the Marquee Club and all those things, she would just go as a school-kid and go and dance to the music, and was with my father as he went through all those early British bands like Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, the Graham Bond Organisation, and moving to Cream. So there was an innocence to that, and then suddenly she wrote two songs with Cream, she wrote “Sleepy Time Time” and “Sweet Wine.” And so she was kind of part of the whole thing in a very, just in a very natural way.

So yeah, but there’s so many stories – I wasn’t born during the Cream era, but there’s so many different things that tie into that music for me personally. You know, obviously, for fans, I’m a fan too. But for fans that aren’t directly connected to it, there are perhaps different resonances with the songs, and whatever. But anyway, that’s one example, I’m sure there are – you know, just the fact that I – we were all in Abbey Road together which is always kind of the sacred, kind of has a sacred element to it, just because of where it is, and there’s a certain – you feel something when you go into that studio.

Absolutely. I mean the history of it, and just to be recording Cream’s songs, you know particularly on bass in the original place where some of those records were created and many, many more…

Yeah. And well, the piano we used on that record is called Challen, C h a double-l e n, and they have two. They’re little cheap upright pianos, but they have had them in that – in Abbey Road since the Sixties, so I think those are the pianos you hear on the Beatles’ records, and you hear them on Dark Side of the Moon, and all those…

No kidding.

And they, you know, that’s one of the wonderful things about that studio is that they have managed to, you know, maintain and restore these instruments, and over the years they have one – they have a kind of, I don’t know what you would call it, a barrelhouse kind of piano that’s you know, sort of piano that sounds a little out of tune and funky.

Courtesy of Malcolm Bruce

Honky-tonk?

Yeah, honky-tonk, yeah that’s a good way of… and they call that Mrs. Mills because during the Beatles’ time, before the Beatles, there was a piano player who was just this housewife, British housewife, and she could play this sort of stride style of British piano playing, and she was bigger than the Beat… she was like number one in the charts when Beatles were number three, or whatever. You know, she’s lost to history now in the bigger picture, but people that are aficionados of, you know British, the history of British popular music will know about Mrs. Mills. You know, she was huge, you know, but she was this like quite portly housewife that just happened to kind of have this incredible talent, but it wasn’t – it wasn’t contemporary pop music, it was harkening back to I guess you could call it pub piano music, like pub as in bar music, you know? But anyway, check it out. Mrs. Mills. But they have an upright piano which is a honky-tonk piano, and still, that’s the one that they call Mrs. Mills.

Very nice. That’s a nice piece of – that’s a nice anecdote.

Yeah, it’s an obscurity. But I mean, I guess to us musicians those things are kind of interesting. Or, well I suppose B.B. King did it, you name your instrument, you know, you give your instrument a name. You know, this is Lucille, or you know, this is like, I’m playing Mrs. Mills.

Nice. Well, with British music it’s hard to imagine how that – what that would have looked like without Cream. And yet, they managed to have such a huge impact in such a short period of time, and by 1968 or by 1969 there was really no more Cream, with the exception of the 2005 reunion.

How – it seems like that was – over the years there was some animosity between Jack and Ginger, and that even though they were one of the – formed one of the most iconic rhythm sections of all time, that they didn’t necessarily always get along as well. How do you think that affected – how do you think that affected the band’s inability to continue, and how do you think that could’ve happened differently, do you think?

I’m not sure – I’m not sure you can reinvent the way things are, you know? At the end of – around 2000, 2001, I spent a week with my dad in LA – in Santa Monica, and he was working with Andy Summers. I’m sure Andy wouldn’t mind me saying this, (laughs) but they, so they actually with the incredible Dennis Chambers on drums, they made a whole record that’s never been released. Andy’s got it somewhere, but I hope it sees the light of day one day. But anyway, like I just remember we were all hanging out, and my dad and Andy would be sort of competing about who fell out in the two bands that they were – you know, Cream versus the Police – because I think those kinds of dynamics within, personalities, power… power struggles, creativity, ego, money, fame, drugs, who knows? I mean, and so, and I think you know, the Police, they are as notorious for that similar dynamic with Sting kind of pushing ahead as the kind of de-facto leader but the others… and they, I’m sure there were fist fights in that band… but I mean, with my dad and Ginger, they had already fallen out before Cream was formed. They were in The Alexis Korner Blues Incorporated. Then Graham Bond was the Hammond player in that and sax player, and he fired himself, Ginger, and my dad from Alexis’s band without telling my dad or Ginger, and formed the Graham Bond Organisation. John McLaughlin was a part of that for a while as well, Dick Heckstall-Smith, the sax player.

And so he fired them without telling Alexis, and I think Alexis eventually forgave them all. But they were a very, very hard-working band, and they were kind of proto fusion, R&B, driving – something very, very new at the time – and they were doing two to three hundred gigs a year, you know, up and down the U.K. But I think that Ginger – by the end of that period of time, Ginger fired my dad from that band at knifepoint, I believe. There are various stories of, you know, cymbals being tossed lovingly across the stage at people’s heads, and whatnot. So there’s all of that – that was you know, around 1965, so at least a year, year and a half before Cream was formed.

Heavenly Cream sessions/ Courtesy of Malcolm Bruce

And then the story goes, as far as I know – and the only one left really is Eric to ask this (laughs) or my mum – but the story goes that Ginger, it was Ginger’s idea to put Cream together and that he went to Eric. Because everyone loved Eric’s playing, my dad played with him at least briefly in John Mayall’s band, and so Ginger went to him and said I want to put a band together, and I want you to be the guitarist, and Eric said only if Jack Bruce is the bass player.

And so Ginger said – or maybe he didn’t say only if, maybe he said I’d like Jack as the bass player if we’re gonna do this – and then so Ginger kind of had to go to my dad and sort of say: “Jack, Ginger (Eric) wants you to be in the band so we’ve gotta make up.” You know, so I think before Cream – all that kind of heaviness was going on, and, but at the same time they had this thing, as you mentioned before, as a rhythm section they were – there was a magic there, there was the incredible thing that they had.

Whether – I’m sure it was partly the friction between them – but I think, you know, I don’t think anyone fully understands – I certainly don’t fully understand, I mean again, Eric might be the person to ask for any insight, whether if he’d want to get into it or not I don’t know, but just… Ginger was maybe three years older than my dad, and he helped my dad, he sort of helped introduce my dad unto the London scene. Because my dad was from Scotland, and he was that bit younger, Ginger was that bit more established. Ginger was a registered heroin addict by the early 60’s, and one of the provisos for Cream was that he would get clean, which he did.

So there were all these kinds of layers of stuff going on, and you know, Ginger maybe was like, you know, the elder brother, but my dad wouldn’t have ever, I doubt my dad would ever accept that, like being beneath somebody, or you know, ‘cause he’s the fiery Scot.

So yeah, just personalities. And I think – I mean I was at the, when they were inducted into the Rock-n-Roll Hall of Fame, I was there. So they did play then, that was 1993 I think. I was in my first band, first signed band, and I was living in Hollywood, and they got inducted in, I can’t remember which hotel it was, but my dad invited me down. And so I sat with them all, and then ZZ Top gave out the award, and they got up and played a couple of songs. But they did play then, and it was wonderful. And also my – Ginger had toured with my dad and played on his solo record. So you know, even though the mythology or the story is that they fell out, they did from time to time reconvene. Although I think, I think they did a tour together but Ginger ended up driving along the tour bus in a car separately, (laughs) so I don’t know. I mean, you know, maybe he wanted to do that, I don’t know.

Was that the 2005 reunion? Or, or during the earlier days?

Way back. I think in the 80s they – my dad made a record which actually I am on one track, I think – he made a record around 1986 or 1987 in San Francisco… the name of it escapes me right this second, but Ginger…

Not BBM?

No, this is, this is just before BBM, a few years before BBM… A Question in Time, that’s it, the album’s called. And it’s got some amazing people on it, it’s got Allan Holdsworth on it, Tony Williams guests on it, and Ginger guests on it. And then I think my dad had a tour to support that record. It was on a major label, I think Epic, or – I’ll have to check that out. But yes, he did a tour of the U.S. and Ginger was on that tour, but I think there were two drummers on the tour, so Ginger would guest but there was another drummer playing for most of the set…

So they did work together off and on many times, and… they loved each other, you know? This is the thing, it’s like… brothers.

Yes. That’s what I…

It’s like brothers who are, like, grabbing each other and punching each other, but they love each other, you know?

Sure.

They were so close, and they had that understanding beyond words, and it’s so emotional, and they’re competing, energetically but I’m not sure if it was about anything specific… I don’t know. So, I don’t know – call up Eric! If you can.

Ironically he has a house here in Columbus Ohio, and he married – his wife is from here in Columbus.

Yes, I heard that, yeah. No, Eric’s lovely, I mean obviously, he has to be careful… you know, he’s quite private, and all of that. But he’s a lovely guy and he’s an amazing person, and I, I love and respect him as many do, you know… incredible talent, and he’s still doing it, which is just amazing, so… But, I’m not sure what he would say about Jack and Ginger (laughs). At this point, he might just shrug his shoulders and say God bless, I don’t know. (laughs)

Well, it makes a lot of sense – the brothers analogy makes a lot of sense, I can see that. Almost like a sibling rivalry, or maybe love/hate, or maybe neither love nor hate, or maybe love but not hate, but just… butting heads.

I mean, I did… in 2016, me and Pete Brown put – that was two years after my dad passed away in 2014 – we organized a tribute concert in London at Shepards Bush Empire, and we had some amazing people come to that… Mick Taylor, Lu Lu, David Sancious, Gary Husband, Dennis Chambers, Corky Lang, all kinds of people came. Clem Clemson, many people who knew and worked with my dad and loved him, so that was amazing.

And so I asked Ginger to come, and he came with Abass Dodoo, his friend, a percussionist friend of mine that was in Ginger’s band but was also his friend. So Abass helped bring Ginger down to that show, and Ginger got up on stage. He didn’t – he played for a few minutes but more than that, he told a story about my dad in front of the whole crowd about how they met. And I think it’s, it’s on YouTube somewhere.

Courtesy of Malcolm Bruce

And I mean, it was just so moving. I mean, it wasn’t somebody that held hatred, it was somebody that loved my dad, you know. So I think, as they say, you know sometimes people are like that. That’s… it’s… you know, we can talk about trauma and abuse, and like sometimes that I think it perpetuates it. So it’s you know, “Well I’m gonna punch you in the face ’cause I’m doing it for your own good.” You know, that sort of thing.

“You asked for it,” type of…

Yeah, “you asked for it. I’m doing it to teach you a lesson because actually I love you.” And it’s like well, all right, and they might even think that’s it’s true, but it’s not exactly that healthy. But maybe there was something going on on that sort of level. You know, working-class kids coming from not the easiest background, but suddenly finding themselves in this kind of elevated position and not really knowing how to handle it, and taking it out on each other maybe. I don’t know, it’s really complex. I’m not going to try and be an analyst too much, you know?

Sure, and it’s hard to demystify it, and even as close as you were to the situation, it’s hard to get inside their heads…

Yeah, and my dad was a very – you know, an amazing person and a beautiful person, but he was multi-layered, he was quite unresolved in certain ways, and quite emotional in certain ways, and you know, in my opinion, a great – a great artist, you know. And I think sometimes with people that for whatever reason have discovered that level of greatness, they don’t necessarily know how to live that well, you know. They don’t necessarily have the same level of skill at living, and dynamics within relationships and all that kind of stuff.

Maybe there’s a – you know, I mean it’s sort of a bit like when the body isn’t balanced, it tends to leech things from the other organs in order to maintain itself, you know. And I think maybe psychologically we can do that… I’m so in the creative process that other things perhaps are not in balance so much. And I think that can happen with creative people, most creative people – I’m hoping that – I’m finding my practiced meditation, you know I take a particular approach to it. And I hope that will give me somewhat more of a balance while still being able to be creative, I don’t know. (Laughs) These are things we’re altogether collectively discovering, right? I mean, what is it to be a human, you know, and what does that mean? You know, is it something we’re told how to be by society, or is it something subjective? I believe it’s completely subjective, to be honest, when it comes down to it. But the generations, you know, sometimes we are… we do learn, and previous generations make mistakes that we can then learn from.

So you know, I don’t judge these things because I’m not inside those people’s heads. And you know, they achieved so many amazing things, but maybe to the detriment of to some degree to their balance in other parts of their lives.

Well, and so often great art or great music comes – is borne from conflict, either inner conflict or interpersonal conflict that it’s, it’s hard to say would some of these great works of art, great works of music have been possible without the conflicts, without that – those interpersonal conflicts or inner turmoil, or that yearning for balance.

Yes, and I think, I mean it can be – and that can manifest in many different ways. I mean, I think about this a lot where… because we have, in order to be creative, we have to kind of create – normally have to create a sort of sacred space. And so if the external world is so traumatizing and so difficult, sometimes we’re just literally forced, we’re forced to kind of go OK, I’m gonna create this like little autistic almost space inside of myself that will not – will have these walls but will not be impacted by whatever’s going on outside. Even if I’m in a warzone I’m still gonna have that thing… I mean, Shostakovich is a good example of that. He’s living in the Stalin era in Moscow, and he’s watching all his friends be kind of carted off never to be seen again, and somehow he survived that. But he found a way to continue to be creative, that’s just one kind of obscure example.

Heavenly Cream sessions/ Courtesy of Malcolm Bruce

But I think, yes, and I think maybe sometimes people can use drugs to do that. You know, drugs that will switch off the inner dialogue and give that space. I don’t find that helpful myself, but meditation seems to do a similar thing where it can clear the energy and create this kind of experience of higher consciousness or whatever you want to call it. But there are plenty of ways of cutting through to that place, that sacred place where the ground state of being, the quantum field where all creativity is there in potential. It’s what we all are, whether we’re experiencing it in that way or not, whether… we might be kind of locked into this more superficial level of the hierarchy of experience, and so we’re not feeling that or experiencing that or we’re not aware of it. But that’s all we are when it all comes down to it. We are the total potential of natural law and creativity, you know?

So some people somehow manage to access it naturally. Other people go, “OK, I’m going to sit on a mountaintop for forty-two years.” Or “I’m gonna take some really strong drugs,” or… I don’t know. I mean, again, there don’t seem to be any rules to it, or haven’t, historically. But I think there are specific methodologies for accessing creativity. You know, meditation seems to be one, but I’m sure there are others, but… yes. I don’t know. I mean, if you’re born into a particular culture, I try to think of that.

You know, my dad being born in 1943 in Scotland, working-class – you know communist, essentially communist atheist family, you know, into a sort of – not ghetto, but certainly a working-class environment with a lot of violence around, everyone’s drinking alcohol all the time, you know, there’s a particular frequency. And so, do you go to work down in a factory and that’s it, you don’t look outside of that, you accept your lot.

But then, that particular generation, post-war, post-Second World War, there was that emergence of the youth culture, and there was the opportunity for working-class people suddenly, with a talent. Whether it was sport, or music, or art, or, or as an actor, or whatever, suddenly all these people were having a voice, and experiencing things that previous working-class generations would never have dreamt. They would, “Yeah, very good, sir. Very good, sir. Yes, I’ll get the door for you, sir. You know, hello, I’ll go quietly,” you know. And suddenly it was something completely different.

I mean, I’m not saying that the true power structures ever really shifted, but at least there was an element of that, that shifted for a moment, where everyone was able to be expressive. And that must have shifted something on an elemental level, whether it was sustainable I don’t know, or whether it was sustained, I don’t know.

I mean, certainly, now we’re in a really interesting time in that regard, aren’t we, I think? You know, what is this – what’s going on here now with economics and expectations for conformity, and all of those kinds of, you know… what kind of lives are we really living? Are we living free – are we free? What are these structures – are they allowing freedom, or through creativity… and you know, there you go.

Again, you know, Cream… a little window to something that may have had some purity in terms of creative expression. Now we have this kind of corporatization of creativity, where it’s all predictable. And some of it might be awesome – an incredible singer, or an incredible guitarist, or whatever – but it’s largely predictable…

More filtered, a little more manufactured…

There’s a form, an expectation to adhere to this thing, and if you don’t, it’s kind of… oh, that must be jazz, then. (Laughs) So yes, I think we’re in a very interesting time because we’re in – we’re in a time where we have the absolute most potential to completely, to make a shift, a quantum shift to higher consciousness, a collective shift as it were… but we’re also on the precipice of self-annihilation. But I don’t think that’s gonna happen, I believe that we’ll turn it around. But then we’ve got artificial intelligence, we’ve got all kinds of forms of manipulation going on in society, psychological warfare, all kinds of stuff going on.

So as an artist, it’s a great time to attempt to express these things, if anyone’s listening. So, yeah.

Well, that’s fascinating, and now I wish that I had more time to kind of delve into that. Did you have the opportunity – you mentioned your upcoming album as well, Fake Humans and Real Dolls. Were you able to delve into some of those existential topics on the new release?

Yes. Well, I’m actually still in the middle of writing, recording. I’ve recorded fifteen songs, but I’ve just, it’s… I have to write more at the moment, because of these things that I’m thinking about. So yeah, absolutely. I think it will be finished in the next few months, and that’s why I’m not rushing it, and it’ll be out next year. I’ll do some single releases leading up to touring, probably next September I’ll be on the road to support that. But yes, it’s all about all of those things that I’m thinking about, you know, as a person.

Well, Malcolm, thank you so much for taking the time today for this interview! It’s been a pleasure to speak with you and hear your unique perspective about so many of these topics.

(The interview concludes before Malcolm’s concluding remarks due to a technical limitation.)

Interview with Cream lyricist Pete Brown

The Top 100 Psychedelic Rock Artists of All Time

The 100 Best Psychedelic Rock Albums of the Golden Age

Gallery

Recent Articles

A Tale of Crescendo ~ Chapter 9: The Clash; Chapter 10: The Reckoning

•

January 26, 2026

Artist Spotlight: Aliume

•

January 24, 2026

Loading...

A Tale of Crescendo ~ Chapter 9: The Clash; Chapter 10: The Reckoning

- Bill Kurzenberger