The Ketamine Conundrum

The Ketamine Conundrum

Buyer Beware

Right off, I should let you know that I believe in psychedelic healing. Psychedelic therapy involves using certain psychoactive plants or synthetic compounds during the treatment for some mental health conditions, the most common being depression, anxiety and PTSD.

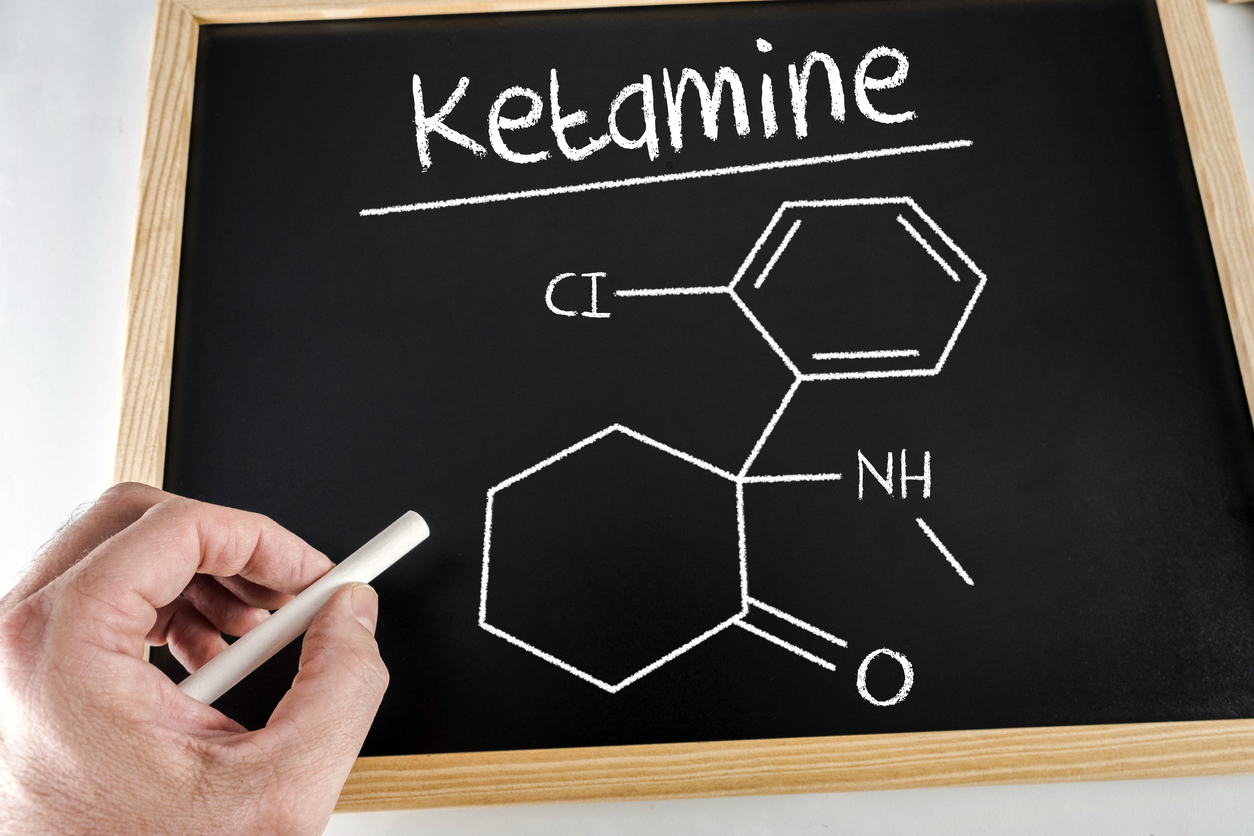

I had heard about a procedure known as ketamine infusion therapy frequently over the past year and was quite curious. Since I’d already decided to wean off the antidepressants I’d been taking for nearly twenty years, I thought it would be a good time to try this relatively new and highly touted approach for depression relief. Also, I was studying to become a psychedelic integration specialist (someone trained to help individuals make sense of their psychedelic experience and implement insights gleaned from it into their daily lives), and ketamine happened to be one of the drugs discussed in my class. Although it’s not a true psychedelic (it’s considered a dissociative anesthetic), it’s the only legal, non-pharmaceutical drug currently being used for treatment-resistant depression in the United States. I wanted to reap the benefits, of course, but the fact that it would also provide first-hand knowledge from the patient perspective was a bonus. By undergoing treatment, I could develop some experience-based empathy to use in practice as a psychedelic integration specialist in a ketamine clinic.

I called a ketamine center not far from my home and was emailed a medical questionnaire, as well as a 344-question psychological screening survey. It was obvious their front-end approach to the procedure was robust, and I was more than happy to comply. After sending in the paperwork, I met with their Health and Wellness Coordinator for a one-on-one psychological evaluation in which she asked me specific details about my depression (e.g., “Do you think about hurting yourself or others?”). After that, there was nothing to do but wait for them to get back to me to let me know if I was a candidate and when we could start.

And then, in this somewhat anxious-ridden interim, without warning, my girlfriend announced, out of the blue, that we were done. She wanted to end our relationship, and there was nothing I could do about it. Suddenly, my reasons for undergoing the ketamine treatment were far more than curiosity. Now I was in despair, and it was urgent. I called and told the clinic I needed help as soon as possible. Fortunately, they could get me in a few days later. That’s when my depression and acute emotional distress were joined by a third element: nervousness. I’ve had a lifelong fear of needles and have fainted quite often from getting injections or having blood drawn. I even passed out once while watching my younger sibling get vaccinated. It’s ironic that I was now willing to submit to having an IV inserted in my arm—for however long it took. But I felt I had no choice. I was in too much emotional pain to turn back now.

My Monday appointment was at ten in the morning. I had to fast from food for six hours and go without liquids for two. And because patients can’t drive after the treatment, I drafted my 80-year-old father into driving me and picking me up. I took the elevator to the 2nd floor. The halls were dark, and there was nobody in sight. I found an office and peered through the Venetian blinds but didn’t see anyone in there either. It felt a bit surreal. But the receptionist, whom I hadn’t seen, had seen me and let me into the waiting area. I was sitting there when a door opened and a rather uncheerful man appeared with a caretaker who was helping him walk feebly past me and out of the office. It wasn’t an encouraging sight.

Shortly, a physician assistant came out, introduced herself as Annie, and asked me if I had any experience with psychedelics. When I said yes, she told me it was a good thing because it would help me know what I was in for. I’d be receiving a small dosage (43 mg) to start, and over three subsequent sessions in the program, they would increase the dosage each time. Then a young, long-haired guy in scrubs and sneakers showed up and asked if I was ready. He took me into a room that was dimmed by blackout curtains and directed me to a recliner.

We had the “needle discussion,” and Connor encouraged me to lie back on the chair. I accepted the inserted IV without fuss, and he said I should let him know when I felt the effects of the medicine. In about three minutes, I felt the vertiginous effects of the drug kick in. It wasn’t that bad, so I put on my headphones and started my playlist. I chose a self-made mix of obscure psychedelic songs from the late 60s and early 70s (https://open.spotify.com/playlist/41ldHag6fuPeaskCuZJVKK?si=8e4876321a0d4c7a). I believe he was still talking to me, but his voice seemed distant and muddled. Anyway, I was getting lost in the sounds of the sublime music I’d brought along.

I lost all sense of what was happening around me. I had no concerns. No sense of time. In fact, I felt like a mush ball. Things were going okay, I guess, until I started to sweat—I mean sweat a lot. I could tell this was probably not normal, because Connor suddenly stood up and started talking to somebody. I couldn’t make out his words, but you know the way voices sound when you’re underwater, right?

Then the door opened, the lights went on, and Annie came in. The look on her face was one of concern. Through the haze I was in and because she asked, I managed to tell her I felt “out of it.” That’s when Connor told me I had fainted—which was rather strange because I was already nearly horizontal. Except for the sweat, it didn’t feel like anything had happened to me, but he said I’d started snoring and my blood pressure had dropped sharply. Annie wondered if she could get me anything. I asked for a washcloth; she brought back a couple of wet napkins and plopped them on my forehead. Connor asked if I wanted to continue the treatment. I did. He resumed administering the ketamine, so I re-applied the headphones and drifted back into the ether. It seemed like only seconds later that he announced my first session was complete.

Two days later, I went back for session two. While Connor prepped my arm, Annie asked if they could keep me on the same dosage as the first time. I asked if there was any medical reason why I shouldn’t get a higher dosage, and she couldn’t think of one. Then I asked why I fainted in the first session, but she didn’t know, since no one else had ever passed out in her office. I instructed her to increase the dose. She asked if I had anxiety. Connor chimed in that I had been fidgety and anxious during the previous session. Annie said I should give consent for an intravenous anti-anxiety medication then and there because, legally, she couldn’t ask once I was under the influence. That made sense, so I gave my consent.

I put on my headphones and leaned back in the recliner. It seemed to take longer for the ketamine to hit me this time—about six or seven minutes (during the third song on my playlist). Just like before, the psychedelic music fit the mood like a charm, and I was enjoying the sounds in my altered state. After a few songs, though, I realized I was drenched in sweat again. Having learned my lesson, I removed the headphones and told Connor—who was typing away on his laptop—that I might pass out again. He stopped the IV and texted Annie to come in. In my hazy state, I did my best to answer her questions, and she instructed Connor to add the anxiety medication to the mix. I leaned back, resumed my playlist, and drifted off—experiencing some bizarre sensations that defy description. Almost immediately (at least, that’s what it felt like), Connor stood up. I took off my headphones. “You’re done,” he announced. Just like that. Nothing further.

But I wasn’t done with the bizarre sensations. I felt round and obese—like an Oompa Loompa—and the headphones seemed to be resting on my enormous double-chin. I waited for that phase to end, after which I returned to a “normal” woozy state.

A couple of hours before the next session, I took a half-milligram of Xanax to counter to my now- anticipated anxiety. It worked; I wasn’t anxious, and it wasn’t necessary to interrupt treatment. I kicked back with another home-crafted, old-school, psychedelic playlist (https://open.spotify.com/playlist/1YJsqEibAgxUDIyrdJ563V?si=09e025c2f5c04b17) and rolled with it. I had a couple of insights—things I really wanted to remember. But I couldn’t recall any of the thoughts that seemed so profound to me at the time. This was upsetting, to say the least.

My fourth and final session, I was again ready with my Xanax. With Connor being out that day, a different paramedic hooked me up to the IV and administered 78 mg, the highest dosage yet. I put on my music and felt the ketamine kick in after a few minutes. With the ineffable taste of anesthesia in my mouth, I drifted off into the nether regions of my mind.

As it had in each session, the music sounded weird and wonderful. At one point, I looked at my phone to see which artist was playing, but my eyes wouldn’t focus. Then I noticed that I had started thinking about my life—in much the same way I normally do. For most of the treatment, I just flowed along on an ethereal river. I wasn’t expecting to have coherent thoughts about my failed relationship, but I did. I was still depressed, and in that moment, the sharp heartache of my breakup—of being dumped—came back. I’d thought we were happy together. We’d always had fun. She’d said she loved me many times, and I’d told her I loved her too. Deep sadness flooded me; the woman I loved didn’t want to be with me any longer.

Then I saw the paramedic stand up out of the corner of my eye. I turned my gaze toward her, but she was out of focus. Even though I had the headphones on, I could hear her ask me how I felt. I took my headphones off and, although her voice was distorted by the drug, she asked me again. I told her, “sad”. There was a pause.

“That’s normal”, she said and then walked out of the room, leaving me alone in the dark room of the clinic.

Epilogue

It’s been ten days since my final ketamine treatment, and I can say for certain that it did not work. Not for me, anyway. I’m not only still depressed, but I think I’m actually worse. Any relief I got was fleeting and definitely not worth that much money or time. It’s too bad, really, because I’d been optimistic going in and wanted it to work.

But what’s more disconcerting is that the clinic does not have anyone with a background in psychology. The staff claim they are effective in treating depression, suicidality, and PTSD—all-too-common psychological conditions. When “patients” show up to be helped, they are often symptomatic, and still, they are induced into an altered state. Ketamine treatment can produce strong emotions, bring up memories, and even trigger previous traumas. Yet, the clinic is unprepared to deal with these critical issues. And considering that some of their clients are seeking this treatment as a last resort, it is unconscionable that there is no psychological support involved in the procedure.

I had gotten a call from Annie, the PA, the day after my final session and told her I felt no relief. She suggested I come back for a couple more sessions and allow her to “get more aggressive.” I said no, and expressed my concern about the lack of a psychological component. Annie said she would have their Health and Wellness Coordinator contact me, and true to her word, that person did. The same young woman, who had initially evaluated me, was a student working toward her Master’s in Child and Family Therapy. From her I learned that they “follow up with every patient, but sometimes we can’t reach them, and we never hear back.” Given that some, if not many, clients are seeking relief from suicidal ideation, this was a disturbing revelation.

I know I would have benefited from the support of someone with a background in psychology and/or psychedelic integration, and I also think an important opportunity for patient feedback was wasted. A qualified staff member could have explored what I’d been thinking just before I passed out in that first session. The clinicians I’d been with may have assumed my fear of needles caused it, but that doesn’t make sense to me because too much time had elapsed between the poke and my passing out. I believe it was a panic attack, despite the anesthesia. It would have made a huge difference if a PI specialist or counselor had asked me what I was thinking and feeling at the time. It’s possible I would have gained profound insight. Instead, I am thousands of dollars poorer and no better off emotionally.

I still believe in psychedelic healing. Even after what happened (or should I say, didn’t happen?). However, ketamine therapy without psychological support seems more like a shameless money-grab more than a comprehensive, compassion-based treatment. I strongly urge readers who are considering ketamine therapy to inquire about psychological services available in conjunction with the treatment. Ketamine, like any psychedelic, is strictly a therapeutic tool and not a magic bullet.

Gallery

Recent Articles

Loading...

Vinyl Relics: Would You Believe with Billy Nicholls

- Farmer John

A Tale of Crescendo ~ Chapter 9: The Clash; Chapter 10: The Reckoning

- Bill Kurzenberger

2 thoughts on “The Ketamine Conundrum”

Thanks for sharing both how the experience takes place and also your disappointment about it, and why. Hang in. Sorry about your depression. Thanks for your magazine.

Thank you, Brian.

Depression is becoming an epidemic in our society. It’s a shame that most ketamine clinics entice clients with hope, but don’t deliver the goods.