Psychotropic Cinema: El Topo

Psychotropic Cinema: El Topo

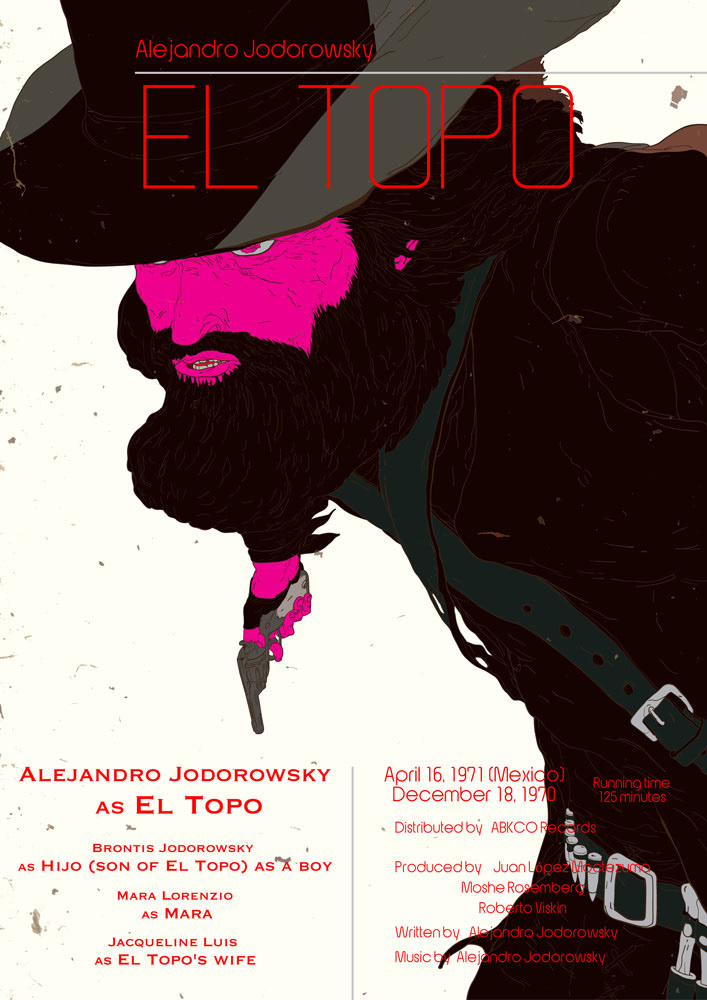

EL TOPO – directed by Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970

*SPOILER ALERTS/PLOT DISCUSSED*

For our readers who do not speak Spanish, “el topo” translates to “the mole”, the blind mammal who lives underground digging tunnels. It is challenging to explicate the experience of El Topo. It is easier to write about its iconoclast director – the legendary Alejandro Jodorowsky – and the context in which the film came to be released, rather than come to terms with the film’s dense, layered symbolism, haunting cinematography, and fable-like story.

As the titular figure himself states at the halfway point: “The desert is a circle, and so we must travel in a spiral.” The film itself has a similar structure, operating on the level of ritual, myth, fairy tale, or psychedelic allegory. Plot, motivation, and character depth are nonexistent. Divided into three sequences, they cast a spell over the viewer, affecting emotional reaction to the imagery while packing in some dense, and, at times, incomprehensible symbolic language.

The first act begins by introducing us to El Topo himself, clad in black leather and riding a horse through the desert with a naked young child (his son, played by Jodorowsky’s own son) in tow. They perform a rite of passage for the boy, burying his teddy bear and a picture of his mother, and ride off. They come across a town where all the inhabitants have been brutally slaughtered. They ride out to the desert and find and kill the perverse bandits, leading them to the leader of the killers, The Colonel, and his five henchmen. The henchmen are torturing a group of Benedictine monks, while the Colonel has a beautiful mistress who assists in his ritual of dressing up in his military uniform. After dispatching the henchmen and castrating the Colonel, El Topo leaves his naked young son to be raised by the monks, and runs off with the mistress, now named Mara.

The second act has El Topo and Mara wandering the desert and making love; the action is all shooting guns and spurts of water. The Freudian symbolism is laid on thick, however the cinematography has a painter’s eye and the inherent strangeness of it all keep the viewer’s attention. In a riff on Macbeth, Mara tells El Topo that she will only love him if he finds and destroys the Four Masters of the Gun, mythical symbols that live in the desert and have almost supernatural powers. El Topo encounters each one, and defeats them all – interestingly by tricking and cheating them – which technically earns him Mara’s love which he no longer yearns for, having been changed by the encounters. Mara leaves him for a mystery woman who is also dressed in black leather (the feminine doppelganger?) and brandishes a whip. They shoot El Topo and he collapses, where he is picked up and carted off by a strange group of deformed and disabled people, transitioning to the third and final act.

The third act takes place twenty years later. The deformed people have brought El Topo back to their cavern hideout, where he is “resurrected” and worshipped as their savior. He takes it upon himself to liberate this group of literal outcasts—he will dig a tunnel and free them from oppression. He takes one of the group, a pretty and meek little person who is in love with him, and witnesses the horror and carnage being perpetrated in the city. He meets the new priest in town, and is shocked and delighted to discover that it is his son, abandoned all those years ago. With the help of these two, he completes the tunnel, his cave-bound disciples escape and are all killed by the citizens, who are waiting in ambush.

El Topo takes his revenge and kills everyone in the city. His son has transformed from a priest into a leather-clad outlaw like El Topo himself, riding off with the little woman and El Topo’s newborn baby. As they ride off into the sunset, El Topo douses himself with kerosene and self-immolates – a shocking yet familiar image to anyone in 1970, as the framing matching the infamous newsreel footage of a Vietnamese monk setting himself on fire.

Jodorowsky’s films are Rorschach tests and the viewer is either entranced by his trippy visions, his earnest satire, his polymorphous perversity, and his firehose of symbols and rituals; or repulsed and offended, angry at its incomprehension, its insistence on the grotesque, its fetishization of violence and blood, and its questionable sexuality. Nobody is indifferent to the film.

El Topo is the original midnight movie, spawning a genre and subculture that still exist today. How it evolved from an obscure surrealist Mexican film with no distribution to become a landmark in cult cinema, is a fascinating story. In 1970, the Elgin Theater in New York City hosted an evening of experimental films made by John Lennon and Yoko Ono. They were approached by an artist friend of Jodorowsky who asked them to please introduce a screening of El Topo afterwards and ask the packed audience to stay. Lennon, Ono, and the audience were absolutely mesmerized, and the theater owner took a gamble and continued midnight screenings every weekend for the stoners and freaks who would line up around the block. The film played to packed houses for over a year. Lennon loved it so much he convinced Allen Klein (the Beatles manager at that time) to buy the rights to the film for wide distribution, which led to its legendary reputation. With Lennon’s help, Klein even personally backed Jodorowsky’s next project, the even more surreal opus The Holy Mountain.

El Topo is quintessentially psychedelic and often described as an acid Western film, and the surreal symbolism, iconoclastic imagery, and dream logic employed showcase its trippy, metaphoric elements. There are multiple queer characters, nudity, sexual violence, indiscriminate murder and gallons of blood. As it is bright primary red and obviously paint, it softens the brutality while also abstracting it. Jodorowsky infamously purchased dozens of animal corpses from a Mexico City slaughterhouse, so while the film does show many real dead animal bodies, they were not killed onscreen. There are moments of sharp satire; the last section’s grotesque city, with slavery and brutality on every corner, has nothing but English signs everywhere implying an American colonial corruption. The church of the city fakes Russian roulette among its parishioners and pretends that they are saved by God’s miracle. Blunt, to be sure, but also liberating and countercultural.

The film wears its Luis Buñuel influences on its sleeve – one of the bandits takes his shoe fetish to absurd lengths – and while there are no hippies per se or drug use, the entire film is hallucinatory. The sound design is experimental with animal noises utilized throughout, as well as the polyrhythmic music composed by Jodorowsky himself. Every character’s voice on screen is dubbed by a different actor. The film’s trance-like spell is psychedelic. Weaving together mythology from Christian, Sufi, Hindu, Tarot, and indigenous cultures, the film itself is not unlike a ritual. Like an acid trip, the viewer may see things differently afterwards.

El Topo is streaming on Amazon Prime and Apple+, and is also online at The Internet Archive. A DVD boxset released by Allen Klein’s ABKCO from 2007 includes his other features Fando Y Lis (1968) and The Holy Mountain (1973).

– Jeff Broitman

Gallery

Recent Articles

Vinyl Relics: Black Kangaroo by Peter Kaukonen

•

February 21, 2026

Podcast–Carlos Tanner

•

February 18, 2026

Loading...