Psychotropic Cinema: I Love You, Alice B. Toklas

Psychotropic Cinema: I Love You, Alice B. Toklas

I LOVE YOU, ALICE B. TOKLAS

Directed by Hy Averback, 1968

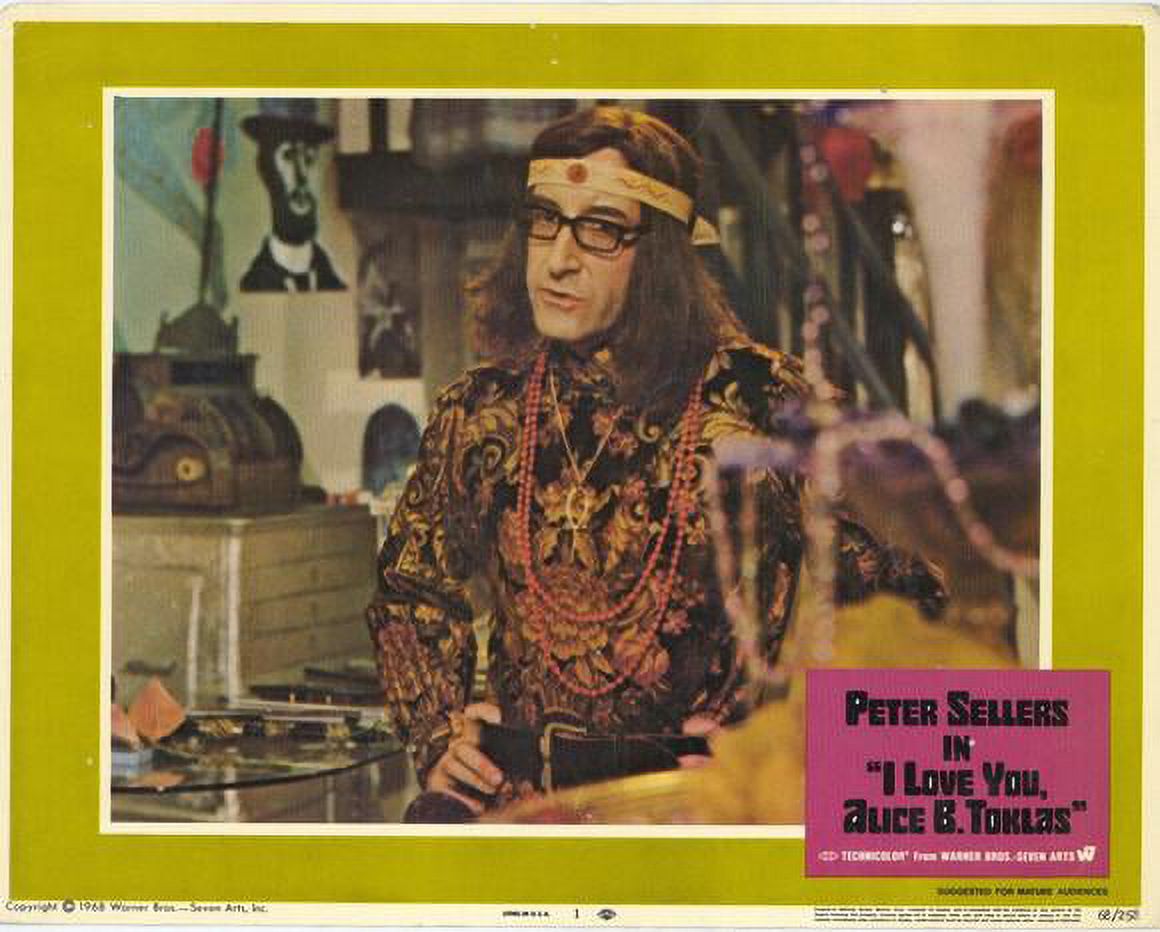

There are basically two kinds of psychotropic films: those made by practitioners trying to communicate and/or recreate an ineffable experience of altered states; and those made by people outside of the subculture, trying to come to terms with the new paradigm. This month’s film is from the latter category. Peter Sellers shines, as usual, in this gently funny, but fairly conventional little “walk on the wild side” riff.

While it may seem odd that Sellers, quintessentially British, is playing a Jewish American nebbish, it actually is of a piece with his many other characterizations and his infamous ability to disappear into a character. It appears that what Sellers is doing is a Woody Allen imitation, an interesting choice because by 1968 Allen, while known as a stand-up and TV talk-show mainstay, was still a year away from his directorial debut, and it wasn’t until the 70s that he became a major cultural figure. But Allen and Sellers had worked together twice by this point, first in What’s New, Pussycat? (1965) and then in the absolutely bonkers train wreck of a film, Casino Royale (1967).

Warner Bros.

The plot: Harold is a milquetoast insurance lawyer, who dates his secretary Joyce and passively acquiesces to the impending wedding because that’s what one does. Like most protagonists, he yearns for something more. After an elderly relative passes away, Harold is instructed to collect his younger brother, a free spirit who has run off to Venice to be a hippie. Harold becomes obsessed with the doe-eyed flower child (Nancy, played by Leigh Taylor-Young) who accompanies them to the funeral. The next week, Harold picks up Nancy hitchhiking and when he finds out that she is homeless, he offers the couch of his tastefully furnished apartment, making a big production out of how he will never open his bedroom door and will respect her privacy, and attempting to be chivalrous.

The next day after Harold leaves for work, she makes a batch of brownies as thanks, and makes sure to add plenty of her pot stash to the mixture. Later Harold, his fiancée Joyce, and his overbearing parents eat the edibles and have a delightful yet confused evening of lowered inhibitions and contagious laughing fits. Once Harold finds Nancy at the boutique she works at, he is enlightened to the effects, which profoundly alters his perspective. When Nancy provocatively shows Harold the butterfly tattoo on her thigh, he’s a goner. He sleeps with Nancy and is incapable of processing his feelings until the day of his wedding to Joyce. In front of their families and friends, Harold can’t bring himself to say “I do” and leaves poor Joyce at the altar, running off to be with Nancy and live the hippie lifestyle.

Warner Bros.

Most surprisingly, Nancy wants to join him (the first hint that things are not what they seem). At first he enjoys a honeymoon period, living in Harold’s Lincoln Continental, now painted with psychedelic slogans and designs. Harold grows his hair, quits his job, and embraces fully the counterculture lifestyle. When cops kick them out of the alley that they’re parking in, they return to Harold’s apartment, turning it into the quintessential crash pad.

But Harold is unhappy and neurotic. He is jealous of Nancy’s free-love philosophy — where she unapologetically enjoys her sexuality with any partner she pleases to and he feels empty after several rude and entitled fools trash his apartment. Harold is too middle-class, and his conventionality keep him from fully embracing the changes.

Eventually, he sours on the whole lifestyle, full of regret… except that the film at this point lurches back to “normalcy” by showing that the previous thirty minutes of screen time, including Harold’s embrace and disillusionment with hippiedom, was actually a daydream fantasy. He’s still there at the altar on his wedding day, which answers the question of why Nancy would agree to run off with Harold in the first place. So he goes through it again, and this time actually does leave Joyce at the altar, but instead of running to his fantasy Nancy, he just runs away, blissfully unsure of his future. He doesn’t know where he is going, and for the first time in the film, he’s happy.

Warner Bros.

Co-writer Paul Mazursky adds some fun editing touches, inspired by the stylistic innovations of the French new wave. There is some blunt satire; at one point, a group of conservatively dressed people leaving a church comment disparagingly about the long-haired freaks wearing strange clothes, while the camera pans to a stained-glass window showing Jesus and his disciples standing in the same position as the hippies. The central scene of the film, when Harold, Joyce, and his parents eat the altered brownies, is presented more positively than any other studio film of the time that showed pot. But there is no attempt to show Harold’s tripping perception; when he does hallucinate, at the end of his altar daydream, it’s only to see his parents and Joyce living the hippie lifestyle too, which horrifies him.

There’s a touch of Reefer Madness camp in the complete personality change they all undergo after ingesting, with Harold’s parents dancing and laughing hysterically, and Joyce practically ripping Harold’s clothes off right there in the living room. Ultimately this is a conventional comedy, aimed at the adults and parents in the 60s who were scared and confused at the cultural changes of the times. The humor in the film is unapologetically middle-aged and Jewish, with Harold’s overbearing mother and his cluelessness in the face of a pretty shiksa hippie chick. Mazursky was one of the men responsible for The Monkees (he co-wrote the pilot) and his screenplay collaborator Larry Gelbart would go on to be one of the driving forces behind the MASH TV show. Director Hy Averback was a veteran TV sitcom director who worked consistently in Hollywood for over 30 years.

Warner Bros.

What of the significance of the title? Alice B. Toklas was the life-partner and muse for famous writer Gertrude Stein, one of the first publicly-acknowledged lesbian relationships in pop culture. In the late 1950s, she published a cookbook which included recipes for dishes submitted by her friends and fellow bohemians. Among these was a simplified recipe for “hash brownies”, submitted by artist Bryan Gysin (technically, the recipe calls for cannabis, but for shorthand slang, the phrase “hash brownies” conveys context). First embraced by the beatniks, the Toklas recipe became infamous in the burgeoning 1960s counterculture, and so the film’s title acts as code for those hip enough to get the reference. When Harold finds out that Nancy spiked the brownies, she says “Don’t blame me — I was following Alice B. Toklas’s recipe,” to which Harold replies with the film’s title.

I Love You, Alice B. Toklas is available to stream from multiple platforms (including Hulu, Apple+ and Amazon Prime) and is also available on DVD from Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.

Jeff Broitman is an actor, frequent writer, and long-time contributor to Psychedelic Scene and the recurring Psychotropic Cinema film review series

Gallery

Recent Articles

Unicorn by Rio Kosta–Album Review

•

February 24, 2026

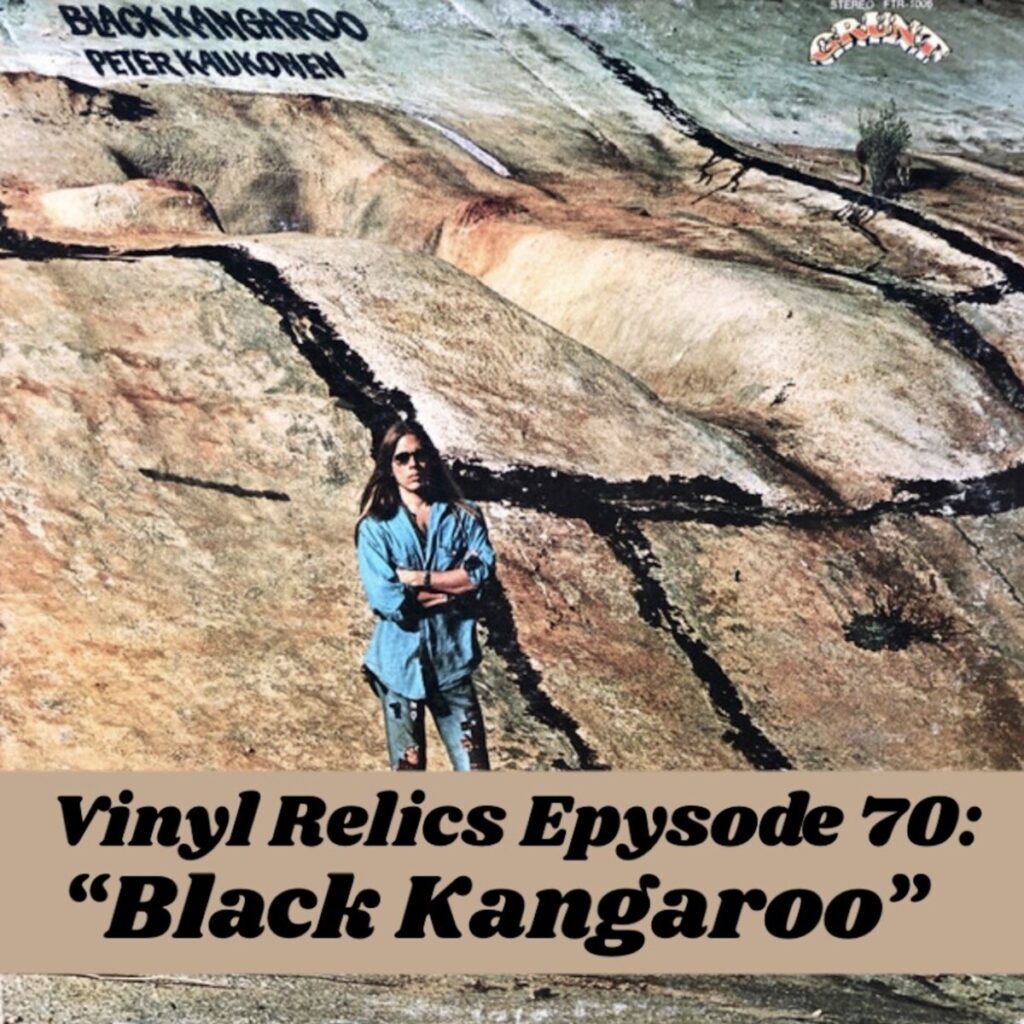

Vinyl Relics: Black Kangaroo by Peter Kaukonen

•

February 21, 2026

Loading...