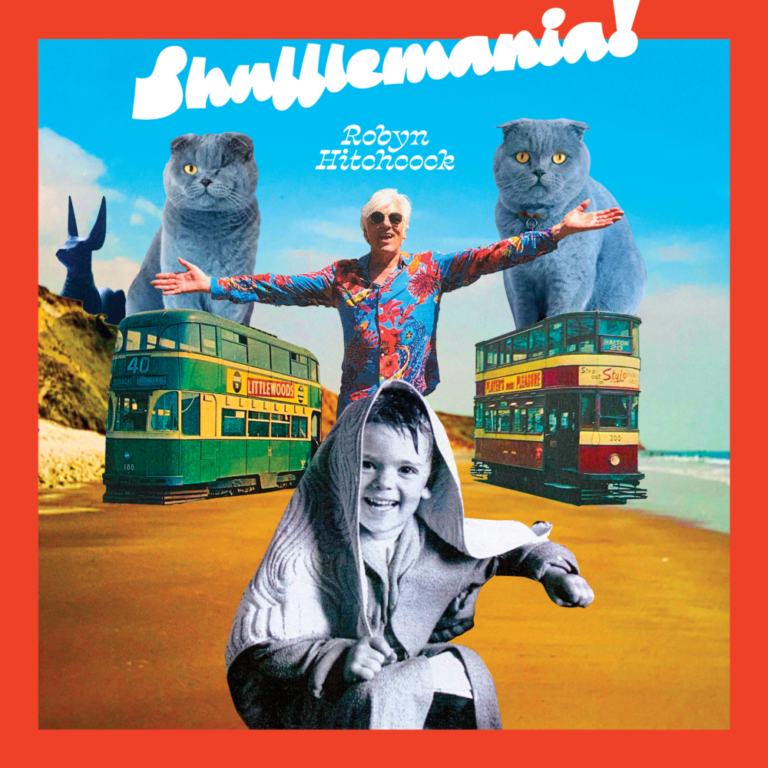

Interview: Robyn Hitchcock

Interview: Robyn Hitchcock

Robyn Hitchcock:

Okay. There we are. I can’t see. So it’s all perfect. Good. Did I send you a copy of the record or did somebody so you heard it?

Jason LeValley of Psychedelic Scene:

I have heard it, yeah. I think it’s great.

Hitchcock:

Oh, thank you.

LeValley:

Yeah, I would say it’s one of your best.

Hitchcock:

Thank you. People generally are being happy with it. Yeah.

LeValley:

So. It’s called Shufflemania! I noticed it’s not up on Spotify. I was wondering if you’re no longer releasing new material on that platform.

Hitchcock:

It won’t be on Spotify for another month. The Tiny Ghost policy is to put things up on streaming after initial sales have gone. So that to begin with, if you want to hear it, you have to buy it. Just to be old fashioned. I don’t use streaming services at all. Emma (Swift), who runs Tiny Ghost, my wife, she put her record out two years ago. Her first full length album, Blonde on the Tracks, which was the first proper Tiny Ghost album release. And she kept that off streaming for a few months, so that’s generally our policy.

LeValley:

I see. So your father was a novelist, and I really don’t know how famous he was, but did you feel like you were being raised by celebrity?

Hitchcock:

Oh, not at all. He wasn’t at all famous. He was even less well known than I am. He was a man in transition. He started out as a soldier. He was wounded in World War II, so he couldn’t bend his right leg for the last nearly 50 years of his life. And then he went to university after the war and became a communications engineer, an engineer, a technical man. I would never have understood what he did, and he wouldn’t have been able to explain it to me. He could have been a spy for all I knew. And then he became a cartoonist and then a painter and then an author. And he had more luck being an author than anything else. But, you know, he sold a few books and plays and a couple of TV scripts, and he had one book made into his first novel, was made into a movie. And that was the thing that brought him most money and most profile. A novel about a man who has a penis transplant and tries to find a donor. So it was sort of marketed as a sex comedy, which it wasn’t really, but my dad was definitely interested in the kind of the comic side of the erotic, and maybe in a particularly English way.

I don’t know, but I’m sure I’ve inherited a fair bit of that. But I went into music, I think, probably maybe unconsciously, so I wouldn’t compete with him because, although I do write and draw and paint, my main gig is as a musician. And Raymond never touched an instrument and was self-confessedly, tone deaf, so he couldn’t sing. So in no way was I competing with my father.

LeValley:

But you have written some short stories.

Hitchcock:

I’ve tried, but in fact, the more I’ve tried to write short stories, the more I know that that’s not for me. I can make things work for like… That’s why I’m a songwriter or a poet. I’m great for four or five verses, but over any length of time, what I do is maybe too saturated, too kind of dense to make sense as a story. Or maybe I can’t create characters that the reader can empathize with or whatever. My dad was, he was basically an ideas man who had put a lot of ideas there’s a whole trunk full of unpublished manuscripts. He may have had, like, six or seven books published in his lifetime, and there’s probably ten times that lying around moldering. They probably will be thrown away or burned when my sisters and I pass on. He wrote three novels about Stonehenge, I think, and none of them came to anything. He wrote quite a few about William Rufus, the son of William the Conqueror. He had certain fixations in time.

LeValley:

I noticed that he wrote a book called Venus 13. And you had a band called Venus 3?

Hitchcock:

Yeah, that was the nod to him. It was Scott McCaughey’s band, The Minus Five, but actually there were only three of them, so I called him The Minus Three for a bit, and then I looked at the name without my glasses, and it looked like Venus. So I thought, yeah, let’s make it the Venus 3, which is a nod to Raymond and Venus 13. Yeah.

LeValley:

Okay. I pretty much know who your musical influences are, but what about your literary influences?

Hitchcock:

Well, my literary influences are kind of chronologically, I suppose. J. G. Ballard and H. G. Wells, who are both kind of classified as science fiction, but were something else, really. They were imaginative short stories that came from a knowledge of what science.. where human knowledge and technical knowhow and thinking was going. But they, I don’t know. It’s a bit like comedy, you know. Was Monty Python comedy? Was Louis Carroll a children’s author? And, you know, did J. G. Ballard write science fiction? But Ballard and H.G. Wells… H.G. Wells wrote the Time Machine, most famously. I don’t know. Have you read H.G. Wells stuff?

LeValley:

Probably, but I can’t really say for sure.

Hitchcock:

Okay. Well, H.G. Wells wrote particularly around the end of the Victorian era, the beginning of the Edwardian so, like, 120 years ago. It’s in an era which would now almost be steampunk to us. Lots of brass knobs and handles and pipes and sort of wooden chests and levers and dials and all that kind of stuff. The first electricity in the very, very early telephones. But I don’t think there were even airplanes when he started. But he wrote a very vivid book about a time traveler, a man who is a Victorian, breathless Victorian gentleman, who invites some friends to supper and shows them this brass contraption he’s got in his front room covered with knobs and dials and levers, and he tells them about how he’s made journeys into the future and it being at the end of humanity and what comes beyond humanity. It’s fascinating. I mean, I read that when I was, like, ten or eleven. That went in very deep. And Ballard wrote a lot of just all sorts of possible situations, but they weren’t all kind of like other worlds or anything. There weren’t really any aliens in Ballard’s world. They were just more unusual processes of thought.

So that was a really big influence on me. And then people like Mervyn Peake. You ever read him?

LeValley:

Never heard of him.

Hitchcock:

M-E-R-V-Y-N-P-E-A-K-E. Mervyn Peak wrote the Gormenghast Trilogy. You’ll have to look up how to spell that. But Gormenghast was a sort of fictitious English type castle in a forest somewhere that was very, very like a cross between a sort of boarding school and a royal family and sort of medieval Victorian place. But they had electricity and gas lamps and horses, and it’s not set in any particular time. That was his main. There were three books of Titus Alone and Gormenghast. It’s really hard to describe briefly, but again, they were quite popular in the sort of hippie era. So I got into Gormanghast when I was 17 or 18– into Mervyn Peake. He was also a really good illustrator, a brilliant… He made his living, actually, by teaching art and by illustrating other people’s work. He did some illustrations of Lewis Carroll. He had a sort of premature breakdown when he was only in his forties, I think, after having to go to Auschwitz and do some drawings. He was a very sensitive man and it didn’t really… Army life didn’t suit him, and going into a concentration camp suited him even less. And he kind of just did like Captain Beef heart.

He went off into some strange sort of premature senility, but those sorts of people, you know, Peake, Ballard, Wells really went right into my hypothalamus, along with sort of similar artists, musicians like Captain Beefheart and Syd Barrett. And of course I love Dylan and the Beatles like millions of mainstream folks, but that was my particular brew of influences, I suppose.

LeValley:

Okay, well, thank you. You did a bit of acting back in the naughts, I believe.

Hitchcock:

Not really. What I did was I did… This was Jonathan Demme, the late film director, who is best known for Silence of the Lambs and then some great movies. He tried never to make the same movie twice, he said, but he was also a big music fan, so he did Stop Making Sense, Talking Heads, which is his most famous movie. But he also worked with Neil Young and.. God, the Feelies, I think. He did The Feelies and he did stuff for people like UB40, but he made an in-concert movie of me in New York in a shop window in 1996,

LeValley: Storefront Hitchcock:

Hitchcock: Storefront Hitchcock, and he kind of liked it. He sort of collected people. If he liked you, he sort of kept you on his books. And I was very lucky. So when he was doing a remake of The Manchurian Candidate a few years later, he got me into being a kind of secondary British villain. And I said, well, it’s nice of you, I’m not really an actor. And he said, It’s all performance. He said, the camera loves you, buddy. So I was very grateful and it helped me out financially at the time, too, so I did that.

And then I was in another one he did called Rachel Getting Married, which had Anne Hathaway in it.

LeValley:

Yes, I saw that. She was great.

Hitchcock:

That was a much lower budget production. I think he didn’t really like having to deal with the big studios. And the big studios, they might still have been working on filming those days. Everything was just expensive. They’d fly you around first class and put you up in nice hotels, get you up at five in the morning so you could sit around in your trailer all day and then say two lines. It was very lush. I enjoyed the life. But Rachel Getting Married was much cheaper I think they funded that themselves. And it was a hit, which was great. One of his later kind of drama movies. He also did a lot of filming down in New Orleans after Katrina went through in Ward 9, I think it is. He’d go down just by himself and talk to people. He liked people. That was the thing with Jonathan.

Transmission disruption

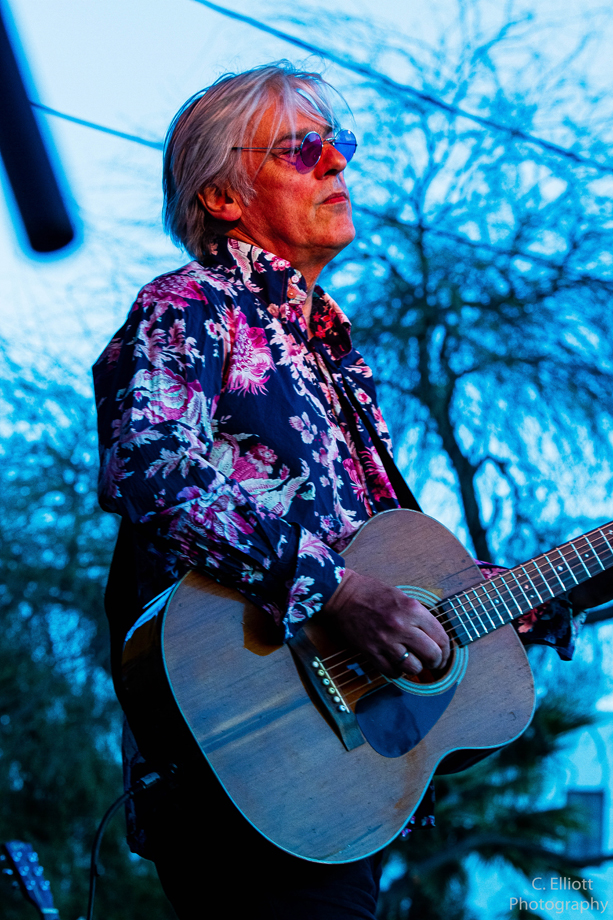

C. Elliott Photography

LeValley:

You lived in Nashville for a while, I believe. What motivated you to move there?

Hitchcock:

Well, I’m still partly there, actually. Why were we in Nashville? Why are we in Nashville? I’m going back there tomorrow. Well, it’s a music place. It’s a great place to be as a musician. And when I got together with Emma, she’s Australian, but she was in Nashville already. And then we scuttled around the planet for a while, lurching between the Isle of Wight and Australia and all sorts of places, and wound up actually getting a place in Nashville, which we still have, and doing a fair amount of recording there. I made my last two records there. I mean, Brendan Benson’s there, he produced my last record and he’s playing on two songs on Shufflemania! He’s on the “Sir Tommy Shovel” and on the first track, “The Shuffle Man” Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings are there and they’re just down the road from us. They played with me and recorded an album I did called Spooked while I was working on The Manchurian Candidate, which was Jonathan Demme and everybody. In some downtime, I came down to Nashville and we recorded a lot of Spooked in a weekend. So we went back and did the rest of it.

Hitchcock:

That wasn’t planned. So there was Gillian and David and then Brendan Benson, who got in touch with me before I even thought of moving out there. Emma had friends in Nashville. Grant Lee Phillips, do you know of him? Grant Lee moved over there about the same time we did. And Sean Nelson has moved there now. Yeah. Just enough people that were in my orbit to make sense for me to be there. And then I met some really terrific players. They were on my 2017 record and whatever else it was called– the most recent one– Shuffleman.

LeValley:

Yeah. So you’ve got some pretty well known musicians playing on that, like Johnny Marr and Sean Lennon, I think.

Hitchcock:

Yes. Brendan’s on it, too. Patrick Sansone from Wilco, he was a neighbor. He did a lot on it, actually. A lot of the songs went to him first, then they went somewhere else. Well, that was the thing. You couldn’t see anybody physically. So it was the reverse of when I made the self-titled record three years, four years earlier–whenever I made it. I couldn’t see a soul, but I could send them things through email. So the whole record was done postally. I just recorded the vocals and the basic guitar, and then I’d send them off to people. Then they’d send them back to me. Then I might re-do my voice or play some extra guitar. But the core tracks were all done at home in East Nashville. So it’s essentially a Nashville record, I think. We finished it here. I did a little bit of the session at Abbey Road just for Shooting Trust. We were able to get into Abbey Road, although we all had to wear masks and stand a long way away from the engineers. But we was between Lockdowns in London, so you could kind of get around and then everything shut down again.

LeValley:

All right, well, I wanted to ask you to what extent your music is informed by psychedelics.

Hitchcock:

Psychedelic drugs?

LeValley:

Yes

Hitcock:

Very much by proxy. Another author that I was influenced by was Aldous Huxley, who, as you know, wrote The Doors of Perception, which I totally absorbed when I was about 14,15. And that whole thing of kind of seeing heaven in your trousers and all the rest of it. jJst that was a very key way of thinking. So the people I listened to, in a way, took all the drugs for me. I mean, particularly, well, all the greats, really: The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Syd Barrett, Captain Beefheart. Lou Reed took different drugs, maybe, but pretty much all of them. Nobody I listened to had not got very high on a whole variety of drugs and most of them had quite a comedown afterwards. So to me, drugs, like alcohol, are really… you’re mortgaging tomorrow by having it today. So, my God, this is fantastic! And then you may go into a deep depression afterwards. Some people are more buoyant and they can survive repeated doses and repeated trips, and other people can’t. I was very cagey about taking LSD, so I didn’t even take it until 1971. I was an old man of 18, and I maybe took it six or seven times over the course of the 70s, not regularly at all.

And I did find things very funny sometimes when I was growing up. I do remember laughing hysterically at some fried eggs and, you know, the whole euphoria thing, Just there’s a point, certainly grass, marijuana, the kind of stuff that we smoked 50 years ago anyway, where you did get the giggles, and it was fantastic. But then you were left feeling hungry and paranoid. It was something you had to do, especially back then.

LeValley:

It was almost mandatory for musicians to take LSD.

Hitchcock:

Mandatory just for a young groover to a young person to at least smoke pot and drop a little bit of acid, and then you might go into other things.

But, actually, what I enjoyed most was mescaline. Organic mescaline. Ever had that?

LeValley:

No.

Hitchcock:

Oh, well, that’s what Alduous Huxley took. It was a white powder, and I only took it maybe three or four times, but it was much gentler than LSD. It wasn’t cut with amphetamines, so it was a sort of gradual kind of high, I suppose. And it was great for listening to the incredible String band on and sort of, I don’t know, looking at drops of water or leaves. The natural world. There was a big emphasis on, “Oh, you’ve got to find the right kind of place”. The ritualistic element to taking psychedelics. You weren’t just supposed to kind of walk down Oxford Street and drop a tab and go into a pub or something. You were meant to go and be with some sympathetic people in some place where there wasn’t a sensory overload and you could gradually let things come to you. But even if you did that, you could get pretty freaked out afterwards. I never had a bad trip, but I wasn’t usually left feeling much better for it. And a couple of places I felt actually quite burned out. I remember my handwriting changed.

(Ringing)

Emma’s phone.

(Stops ringing)

LeValley:

Okay.There we go.

Hitchcock:

The magic of these are all miracles undreamt of in 1970. You still there?

LeValley:

I’m still here.

courtesy of Robyn Hitchcock

Hitchcock:

Great. Okay, now there’s just me on the screen for some reason. I don’t know. Did you take a lot?

LeValley:

Well, yeah, I’m fairly experienced with them. Yes.

Hitchcock:

Did you take peyote?

LeValley:

No, pretty much just LSD and mushrooms.

Hitchcock:

Okay. Because, I mean, I don’t know if you’re in peyote country, but there’s all those things like Ayahuasca and peyote, right? Yeah.

LeValley:

I think that’s a little further south in Mexico.

Hitchcock:

All right. Well, I don’t fancy them because they make you vomit, supposedly. But I feel like if I was to take anything again it would be to take ritual psychedelics like peyote or possibly mushrooms in the right circumstances. I never really got very far with them. But the whole thing with drugs is–drugs in the inverted commas in which we use them. I mean, I saw people getting very inspired and then I saw them getting very burned out. And I’m also a very active person. I don’t really like to just sit and stare into space. I used to get stoned, get high and try and write poems or draw, but actually it didn’t help. Marijuana exaggerates the importance of your thoughts so they can become quite overwhelming. And when I tried writing poems on LSD, I remember thinking, “Well, why write a poem? It’s all there in front of you. What are you writing about? What are you drawing about?” Just look, you know, it’s there and it kind of …I think maybe acid kind of dwarfed my ego and marijuana kind of expanded it. But neither was very good for me as someone who is a compulsive artist and musician.

The only thing I did get from taking LSD was playing electric guitar. One evening I borrowed someone’s electric guitar and I realized that you could get that what I call the wire-between-the-ears sound, which you hear in things like “Interstellar Overdrive” by Pink Floyd and “Eight Miles High”, the McGuinn twelve-string sound and a little bit in things like when The Beatles are being Byrds-y, things like “She Said She Said”.

LeValley:

What sound are you talking about?

Hitchcock:

I call it the wire-between-the-ears sound. It’s like you hit a couple of notes, a couple of E notes and a couple of strings, and they just kind of jangle. They just go between your ears like a wire.

LeValley:

Okay.

Hitchcock:

I saw how that sound it had obviously influenced Syd Barrett. It obviously influenced Jim McGuinn. It obviously influenced George Harrison. It was just that kind of acid spangle noise. But I loved it anyway. I liked it before I even took LSD. So LSD just sort of “Oh, I see!” Maybe that’s where they got it from. So I really like that way of thinking and I like that kind of sound. But I don’t necessarily want to have to take a drug to channel it, to make it happen or to enjoy it. I sort of feel like music that you have to be high to enjoy, I’m not sure about. And I think if it’s good, it can get to you. Absolutely. Blood is pure as a mountain stream. I’m not a purist and I don’t lead that time of life, whatever the word for it is. I’m not a sober–chaste and sober–individual at all. But I think in terms of working, playing on stage, and writing and drawing, I just like to keep a clear head.

LeValley:

Yeah. And I think you can still draw from your prior experiences at any given point.

Hitchcock:

I can draw. And I think of also like people like Salvador Dali, Heironymous Bosch or Giorgio de Chirico or Max Ernst or Rene Magritte. A lot of the people that the psychedelic folk latched on to, I did as a very young man. But I don’t know if any of those guys actually took any drugs. I feel like that’s there in your subconscious if you know how to access it. And just, 60s was a period of accessing it and it became important, you know, same as Jung had been around. So the unconscious–the subconscious was identified and ripe for investigating. And Huxley was a very erudite dude and a great novelist and, above all, a fantastic, real thinker. And he latched onto mescaline. So you had to take that stuff.

Related: The Top 100 Psychedelic Rock Artists of All Time

The Top 100 Neo-Psychedelic Albums

Psychedelic Rock in the 80s

Psychedelic Rock in the 90s

C. Elliott Photography

Gallery

Recent Articles

Can Molly Mend Your Marriage?

•

February 16, 2026

Immer Für Immer by Flying Moon in Space–Album Review

•

February 13, 2026

Loading...